Britain urgently needs to shift away from using natural gas for heating, hot water, and cooking. Gas is mostly methane, a fossil fuel, and its price fluctuates hugely on international markets, while there is an increasing understanding of the health risks associated with open gas flames in the home.

Yet the burning of gas in the home is a deeply ingrained aspect of people’s everyday lives, something I’ve discovered as part of ongoing research into the role of marketing and advertising in the 20th century in shaping perceptions of natural gas.

Shifting away from gas is therefore more than just a technical problem – it will also require an understanding of emotional and cultural relationships with this fuel. To persuade people to embrace the new technologies and ways of life which will help to decarbonise domestic energy, we’ll have to reverse-engineer the relationship between gas and modern life.

1800s high-tech

Gas lighting, stoves and fires were the technological cutting edge of the early 19th century. Gas fuelled the industrial revolution, not least because it allowed factories to extend their working hours late into the night. The first gas company was founded in Britain in 1812 in London and by the 1820s many cities were using gas for lighting and heat.

The fuel in this era was different to the gas we use today as it was manufactured by heating coal, and later oil, to produce methane. This “town gas”, or coal gas, was toxic and highly polluting and became increasingly outmoded as electricity became more available.

After the second world war, as the vast constellation of gas companies were nationalised under the Gas Council and 12 regional gas boards, the industry recognised that it had an image problem. Under the guidance of founder member of the Gas Council Sir Kenneth Hutchison, the industry set about working to transform its image for the post-war era.

Part of this effort was technological, creating new cleaner methods of producing gas and importing liquid natural gas by sea from North America and later Algeria. But just as important if not more were efforts to transform the image of the fuel itself.

Something exciting is happening

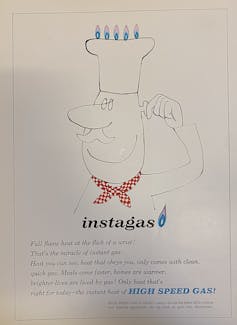

In 1962, the council hired the advertising agency Colman, Prentis & Varley, and launched a new campaign. In a booklet created to explain the campaign to regional gas boards the council set out its intention to convince the public that “something exciting is happening to gas”.

Market research led the advertising agency to focus on speed and heat as the key advantages of gas. This idea, and the resulting slogan “High Speed Gas” transformed its reputation.

The campaign told customers that “Meals come faster, homes are warmer, brighter lives are lived by gas!” Through successive marketing campaigns gas came to represent not only a means to heat the home, but a cornerstone of contemporary domestic life.

Two years later, in 1964, natural gas was discovered underneath the North Sea. Plentiful supplies of a supposedly clean new energy source were soon available to Britain, and by 1967 gas started arriving on the mainland at Bacton in Norfolk, and was piped through a newly-established national grid. Over less than a decade tens of millions of appliances that ran on town or coal gas were converted to use natural gas through a centralised effort under the newly-formed British Gas Corporation.

One of the things I am interested in finding in the archives is evidence of the impact of natural gas on domestic life. For instance at the Ideal Homes show in 1972, gas central heating was sold as a way to alter the very architecture of your home. In the catalogue the headline for the section on the gas pavilion is “Find Space for Living Here”.

Gas appliances were more compact than their rivals, but the implication was more than that. Natural gas had made it easier and more economical to centrally heat a whole house, which meant even in cold weather home owners were able to use more than just the area around a fire.

The fuel and associated technology was therefore sold as a way to expand the space of the home, it would make the home a space of leisure as well as shelter. The catalogue claimed: “One of the top priorities in many British homes; no longer a luxury enjoyed only by the affluent few, central heating is now regarded as a necessity for comfortable life”. The transition to natural gas was presented as a way to transform and improve the homes of the British public.

Today, natural gas is a fuel which we take for granted. This is in part a consequence of the success of the marketing efforts decades ago. Now we face an urgent need to reassess our relationship with domestic energy, particularly gas. But it is not sufficient to tell this story through punitive narratives of energy saving and environmental catastrophe.

The equivalent of “something exciting is happening to gas” is needed to create enthusiasm today for insulation, induction cookers, heat pumps and other adaptations, even if the exact technological direction of this transition is far from settled (see for example debates over the suitability of hydrogen as a replacement for natural gas).

None of this will be possible without national level intervention on the scale of that enacted by the Gas Council and the nationalised British Gas, but we cannot ignore the role of culture in bringing about this transformation either.

There are lessons from what worked with gas. For instance, the task of retrofitting millions of homes to make them more energy efficient should be communicated as a way to create a new kind of domestic space, a desirable and positive transformation of the home into a space that will improve our quality of life in this century.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Sam Johnson-Schlee receives funding from the British Academy as part of their innovation fellowship scheme. His book 'Living Rooms' on the history and theory of ideal homes is published this month by Peninsula Press.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.