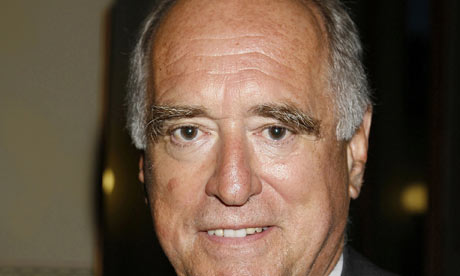

The timing of Football League chairman Lord Mawhinney's intervention in the debate over the future of football was no accident. With the play-off finals looming this weekend, and all the usual hyperbole about the £60m at stake for the winners of the golden ticket into the Premier League lottery, the financial gulf between the Football League and the Premier League is higher on the agenda than at any other time of the year.

Add in the quirk of this year's league tables, with three relatively recently relegated Premier League clubs with stadia and wage bills to match slipping into League One (Norwich City, Charlton Athletic and up-for-sale Southampton). Then stir in a dash of the looming financial woes for a string of Football League clubs suffering from a combination of the economic slump (which has hit some of them, with their greater reliance on local sponsors and on-the-day admission, harder so far than the Premier League giants) and hardening attitudes of the banks and Revenue & Customs, and you've got a potent cocktail of gloom.

Mawhinney's ideas for a cure range from the vaguely possible to the highly improbable. In the former camp he would like to see the FA and the Premier League join the Football League in lobbying Fifa to scrap the window for transfers between domestic clubs. The theory being that it would help out lower-league clubs because they would be able to fall back on flogging their star player to stay afloat during the season and that Premier League clubs would be more likely to take a chance on Football League players if they were all they could get their hands on outside the window.

One old idea dusted off by Mawhinney that may gain some traction is to pool the Football League's television rights with the Premier League and share the proceeds. In what must rank, among some pretty tough competition, as one of the worst footballing administration mistakes of all time, just such an offer was made by then Premier League chief executive, Rick Parry, in 1996, four years after the top clubs broke away. He offered to sell the TV rights for both leagues and share the proceeds on an 80-20 split. It was knocked back by the Football League board and the rest – spiralling Premier League TV deals, collapse of ITV Digital and all – is history. Under their most recent deals, the Football League brought in £264m over three years (itself an increase of 130%) and the Premier League banked £1.8bn. The hope would be that by combining the rights, the expertise of the Premier League and its advisers in selling and packaging them would lead to an increased cake for all. As such, it might be tempting for the Premier League as a means of tackling the issue of "competitive balance" without necessarily hitting its own revenues.

But there would also be those around the Premier League boardroom table who will argue vociferously that adding Football League matches to its premium product would substantially devalue it, making it more difficult to sell at home and abroad. It could even, they might argue, impact on the Football League's successful attempts in recent years to rebrand it as complementary to, rather than in competition with, the Premier League.

A more radical idea is effectively to tax the Premier League clubs a percentage of their annual wage bill that would then be split between the Football League clubs. This, claims Mawhinney, would help mitigate against the "ripple effect" that, he argues, leads to wage inflation in the Premier League trickling down to the Football League. The Premier League refuses even to entertain the concept. Just because Tom Cruise is paid top dollar, they argue, it doesn't follow that the extras expect a corresponding uplift.

They point to their existing "solidarity payments" of between £22m and £44m a year (depending on whether a recently relegated club bounces straight back and the second year of the "parachute payment" is reinvested), some of which is ringfenced for youth development (£5.4m) and community projects (£4m). Nor, they will argue, do clubs have that sort of money spare in their highly geared business plans – most of it is spent. Which is another issue altogether.

The wages distribution plan would get short shrift from the Premier League and – under the "be careful what you wish for" premise – could even accelerate still fairly unformed plans for a Premier League 2 that would simply see the biggest Championship clubs ascending into the gilded cage and the rest cast adrift.

The other key idea – to force clubs to stay up to date with their payments to Revenue and Customs or face a ban on signing new players – is eminently sensible. Mawhinney hopes it will act as an "early-warning system" that will force clubs to put the financial brakes on and avoid so many being tipped into administration and beginning the onerous Luton Town-style points deduction spiral.

To no one's great surprise, the Premier League's recent contribution to the debate started by the culture secretary, Andy Burnham, centred on financial controls for its own clubs and tentative proposals around home-grown players rather than the issue of "competitive balance". But there has been a noticeable shift in the tone of the Premier League and the man who sets it, the chief executive Richard Scudamore, in recent months.

Whether through political expediency or a looming realisation that the shifting sands of global football politics and Westminster threatened to leave it isolated if Scudamore did not engage with issues around financial controls and home-grown players, the Premier League has decided to play ball.

Burnham, who has a long history with many of these issues dating back to his time as secretary for the Football Taskforce, deserves credit for cajoling football to face up to some of the pressing issues threatening it. But he continues to walk a dangerous line between being seen to ask probing questions and telling football what to do – any suspicion of the latter would go down badly at Fifa in the midst of a World Cup bid.

Attention will now turn to the FA chairman, Lord Triesman, who has yet to post his reply to Burnham seven months on and will outline his proposals at a board meeting today. Many of the seven questions lead back to the need for the FA to reform its byzantine structure, broaden its power base and allow its more capable executives to get on with the job without being constrained by bureaucracy. Having allowed the Premier League and Football League to steal a march by making their responses to Burnham public first, Triesman will put forward his plan for the FA to re-establish itself as the game's leading voice and respected regulator. But first it must prove – to the professional leagues, to fans, to players, to the government – that it is up to the job. On past form, that will not be easy.