The road from Pittsburgh reaches the edge of Braddock at the brow of a hill, allowing a momentary glimpse of the Edgar Thomson steel works at the opposite end of town. The view foreshadows what lies ahead: everything between this point and that was in some way affected by the fortunes of that looming factory.

The steel plant was built in 1873 by Andrew Carnegie on the site of a battle of the French and Indian War. It’s construction brought with it prosperity, business, grand public works, and people — the town was home to some 20,000 residents at its peak, many of them immigrants. Its demise in the 1970s and 80s, along with much of the American steel industry, robbed the town of almost everything it had given. Braddock became a byword for post-industrial decline and Rust Belt malaise

White flight followed the steel plant’s fall, and Braddock’s population declined further to below 2,000 today, close to 70 per cent of whom are Black or African American. Its residents were subject to racist redlining and rampant crime. Businesses closed and buildings lay abandoned. Nearly 35 per cent live below the poverty line.

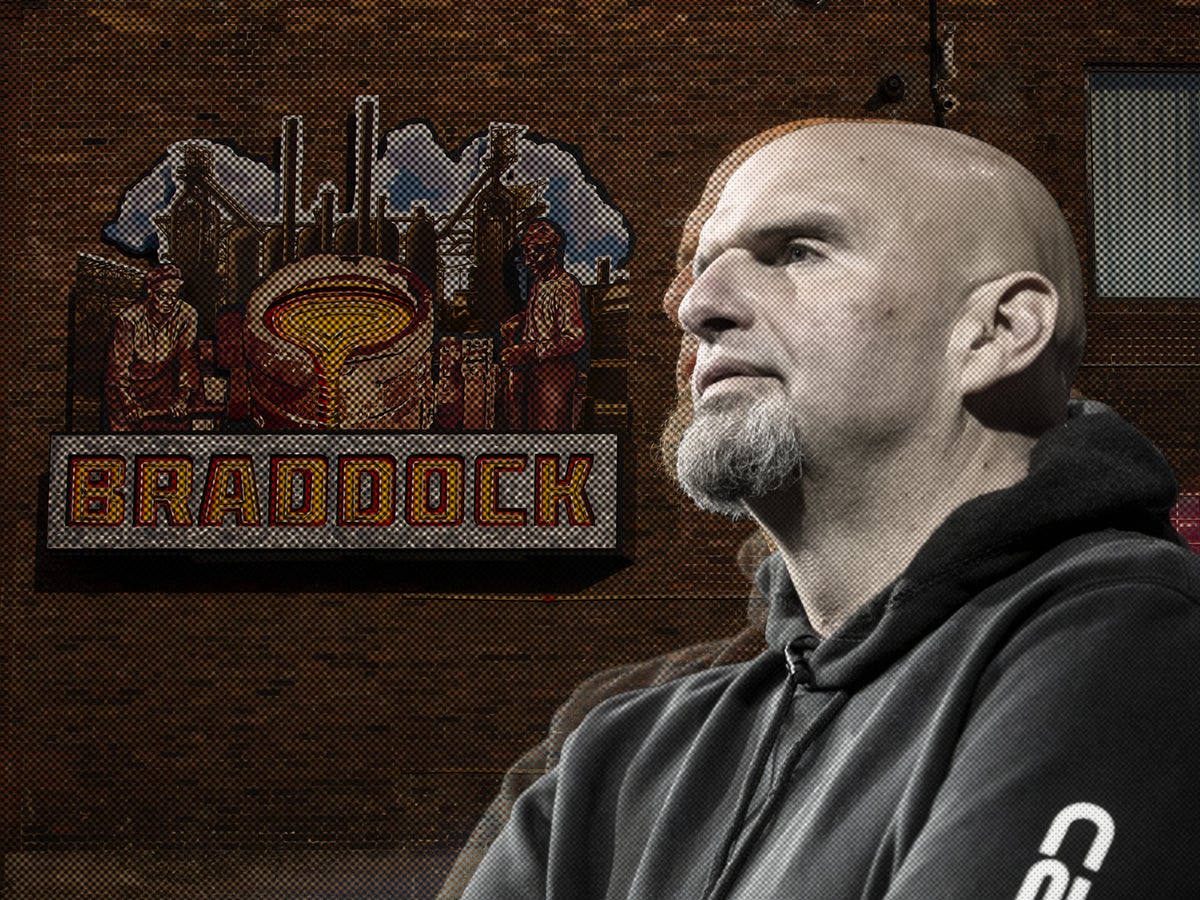

This historic town didn’t make the news much in the years that followed — at least for anything positive. That was until an enterprising and energetic new mayor named John Fetterman arrived and provoked a thousand magazine stories.

Fetterman, who grew up in a reasonably wealthy family in York, Pennsylvania, moved to Braddock in 2001 to start a GED programme. He fell in love with the town’s “malignant beauty,” as he called it. Four years later, he ran for mayor and won. It was the work he did here in Braddock during his tenure as mayor that propelled him to the national spotlight. A tattooed, 6ft8 Harvard graduate trying to resurrect a town through innovation, art, blood, sweat and tears, drew journalists by the dozen. For many, he embodied hope in a place that was in short supply.

That national spotlight provided Fetterman a platform that led to a run for the United States Senate, and there is every chance he could win. But how does Braddock, the town that made John Fetterman, feel about his national ambitions? And as he sets his sights on Washington, what legacy will he leave behind?

You don’t have to look far for signs of Fetterman’s impact on the town. One day last week, a crowd of people gathered in a car park outside the Free Store, a charity where people can donate items such as clothes, furniture, or electrical goods and take them away for free. It’s founder Gisele Fetterman, an activist, campaigner and Mr Fetterman’s wife, was in the midst of the crowd, handing out clothes and directing volunteers, as she does several times a week.

“We’re almost ten years old,” Gisele told The Independent of the Free Store. “I wanted a place where this exchange of goods can happen. I came to this country as a young immigrant, I did a lot of curb shopping, I did a lot of dumpster diving, and I saw that there was so much surplus — so many people had to have so much, and so many had so little, so I wanted to create a space where that could happen.”

Lashay Lindsay, who was parsing some of the goods, describes the store as “wonderful,” and says she’s “thankful” for what the Fettermans have done for the town.

“For a while, it was dead out here, but they are trying to do more for the community. I think them bringing a lot more business here has uplifted the community over the last ten years,” Lindsay told The Independent.

The Free Store was launched with help from a nonprofit founded by Fetterman in 2003 called Braddock Redux, which was aimed at helping at-risk disadvantaged young people in the town. It later evolved into something of a wide-ranging charitable behemoth.

It was one of the many magazine articles written about Fetterman that reportedly brought Gisele to the town. She read about Braddock, about him, and decided to write him a letter. A year later they were married.

Between them, the Fettermans launched a series of non-profit organisations aimed at bringing Braddock back to life. They each had their own projects, but they shared a common goal. It was a partnership — one that extends to this day. Gisele is a popular presence on the campaign trail alongside her husband.

Fetterman already had a few projects behind him when Gisele arrived. His first was setting up a country-sponsored GED programme for young people in 2001. Four years later, those same kids helped him win his election for mayor. He won a crowded primary by one vote.

His 13-year tenure as mayor earned him a reputation as someone who cared deeply about his newly adopted home. His tattooed arms were a demonstration of that commitment: On his right arm, he has the dates of murders that took place in Braddock while he was mayor. On his left arm, he has Braddock’s zip code.

Fetterman took a novel approach to his mayoral duties. Rather than work through the town council, which he viewed as ineffective, he sought to secure investment on his own and deliver it to the town through his nonprofit.

In a 2010 interview with Harvard Magazine, he described himself as a “micro-philanthropist.”

“Making significant improvements in and beating back what many would say is the inevitable decline and implosion of a post-industrial community—isn’t this why you go to a public-policy school?” he asked.

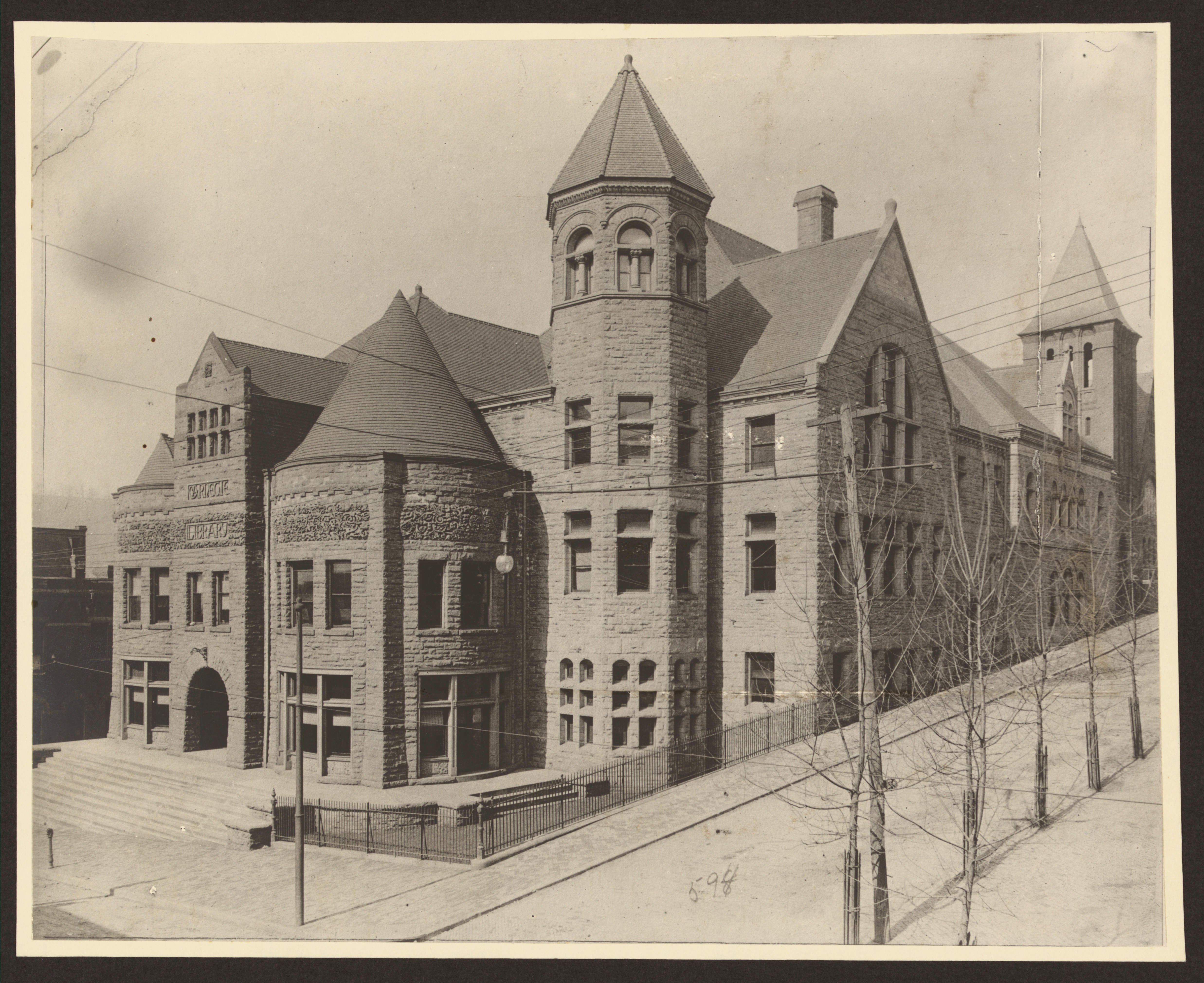

Among the boarded-up shops along Braddock Avenue, the main street that runs through the centre of the town, there are signs of the town’s prosperous past. There is the old multi-level Ohringer Furniture store, the grand First National Bank building, the Carnegie Free Library — built in 1888, the first of its kind in the United States, and recognised as a National Historic Landmark.

Many of those grand buildings lay empty and fell into disrepair for years. Fetterman was responsible for bringing many of them back to life and repurposing them for the community.

Braddock Redux, which was originally funded by Fetterman’s family money, went on to purchase a number of empty buildings in the town to create community spaces. The disused furniture store became a studio and gallery for artists. They built a pizza kitchen and a foster home for children. Fetterman also started the Braddock Youth Project, which aimed to give young people in the town spaces and things to do.

One of Fetterman’s greatest successes in Braddock came when he secured millions of dollars from Levi’s for an ad campaign in the town. Levi’s cast real Braddock residents in the commercial and agreed to give more than $1 million to help finance a community centre and support the Braddock Urban Farm, which Fetterman helped found. Fetterman, who was not paid for his part, provided a voiceover for the ad: "Ninety percent of our town is in a landfill somewhere. So reinvention is our only option."

As well as bringing in funding for economic development, Fetterman focused heavily on reducing crime. Oversight of police is one of the few official roles of the town’s mayor, but Fetterman was known for taking a hands-off approach to the department. Braddock Redux donated some $30,000 to the town council to install surveillance cameras in “crime-prone areas” of the borough, a move which was later credited with reducing crime. In May 2013, Fetterman celebrated five years without a murder in Braddock.

But Fetterman was not without his critics. Very few people know what it’s like to be the mayor of a place like Braddock. One person who does is Chardae Jones, who succeeded Fetterman and served one term as interim mayor.

Jones, 33, grew up in Braddock, like her parents and grandparents.

“My grandfather would tell me about what it was like. It was thriving. People would come from the city to come shopping on Braddock Avenue. My grandma worked at the grocery store there. There was a movie theatre, a furniture store — people would come from all over to just go shopping,” she told The Independent in a phone call last week.

Jones watched Fetterman’s time as mayor with interest, and she was grateful for the attention he brought to Braddock. However, something bothered her about his methods. She says a lot of the projects he launched were done so without collaboration with the local community, and that caused problems in the long run.

“For example, we had a fine dining restaurant and […] it’s a predominantly poor community, so a lot of people couldn’t eat there,” she says, referring to a fine dining restaurant that was opened with help from Fetterman and a Kickstarter campaign, only to later close during the pandemic.

“A lot of the projects didn’t have the sustainability insight built into them at all. A lot of them don’t exist anymore — except the Free Store. Gisele’s a saint,” she adds.

She says the lack of sustainability was a kind of torment for the mostly working-class residents of Braddock. Like the steelworks that brought this town prosperity only to take it away again, leaving an empty shell.

“When you grew up poor, you don’t know you’re poor. When you’re a kid, you just know you’re having fun, but I think people would rather not have these things like the programming and all these awesome things with no sustainability in sight, then get them and then they’re gone.”

Jones believes the root cause of these missteps was an unwillingness to collaborate — he didn’t seek buy-in from the community he was representing.

“A great example is there was a park built on Braddock Avenue. Fabulous park. Awesome. I remember the ribbon cutting. It was built less than a block down from a rehabilitation center that had been in the community for decades, and some people from the community actually work there. They tried to shut that down because it was too close to the park,” she says.

That continued when she took over as mayor, she says.

“I actually lived two doors down from John Fetterman when I was in office for two years and I never actually had a conversation with him.”

When asked what he should have done different, Jones says: “I guess more asking the community what they wanted instead of coming in and saying, ‘Hey, I think we need this, this and this.’”

Jones caused a brief media furore when she decided not to endorse Fetterman in the Democratic primary, instead opting to support his rival Malcolm Kenyatta. She says she was swayed by Fetterman’s tacit support for fracking, a practice he once opposed. She says that decision cost her a friendship with Gisele.

“It’s sad because I tell everybody that if she was running I would endorse her and vote for her tenfold. I’ve always seen her in the community,” she says.

Nevertheless, Jones says she will still vote for Fetterman in November.

The Fetterman campaign has also had to contend with criticism from both Democrats and Republicans for a 2013 incident in which Fetterman chased down a Black jogger with a shotgun. Fetterman said he heard gunshots near his home and saw a man running away, so he chased him down and called 911, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. Christopher Miyares, who is currently in prison, wrote to the Inquirer saying that Fetterman “lied about everything” in his account of the incident, but added: “Even with everything I said, it is inhumane to believe one mistake should define a man’s life [...] I hope he gets to be a Senator.”

Jones’s view of Fetterman is not shared by her successor, however. Braddock’s current mayor, Delia Lennon-Winstead, marched in Pittsburgh’s Labor Day parade carrying a Fetterman campaign sign.

“He’s got heart and passion, wisdom, plenty of love, knowledge, respect for others, the ones who are trampled over,” she told The Independent at the end of the march.

She describes her hometown as “filled with love and hope and morals and respect, but it’s also broken.”

“John kept the crime down - there were no killings for five years. He brought hope to our young people. He opened up youth programmes, fixed our playground and he walked the streets and talked to people — especially young people,” she says. “Our town got a battery jolt. As our senator he’s gonna dig in deeper.”

Fetterman’s pitch to Pennsylvania is somewhat unique in Democratic politics. He ticks most progressive boxes on policy: he’s an advocate of legal weed, for LGBT rights and against corporate greed. He also talks directly to the voters of deprived industrial towns like Braddock — places that largely voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and who Democrats have struggled to reach since in the last decade.

“I said this from before the election, he is a uniquely distinctive and popular individual in Pennsylvania. Don’t ever make the mistake of underestimating his appeal. I warned our party that this was going to be a brawl. And that’s exactly what it turned out to be,” he told The Independent in an interview shortly after the 2020 election, when Fetterman was lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania and Mr Trump was trying to overturn the state’s election.

The hard part about defining Fetterman’s legacy in Braddock is that he is always going to be judged by the standards of his most glowing magazine profiles, of which there were many.

Kristen Michaels, the co-founder of a nonprofit called “For Good” with Gisele Fetterman, lives near Braddock. She runs a women’s incubator with Gisele in a formerly rundown pharmacy and has seen their work up close for years.

“What the Fettermans have done here is pretty incredible. No one is a savior. I don’t believe that John ever came here with that in mind. But what they have done is just loved on this town for 15 years,” she told The Independent.

“I don’t want to speak for this community, I don’t think it’s appropriate, but to have a family who has put in every day for 15 years taking care of people, I don’t think that can’t have an impact, especially in a community this size. So I’m not saying it’s fixed, I’m not saying it’s perfect, but it’s been really something to watch,” she adds.

Gisele Fetterman has her own metric for judging the success of the work being done in Braddock, not just by herself and her husband.

“It’s now a place that people want to live. When we got here a lot of people had left, and when someone that used to live here says ‘oh I really want to move back,’ that means a lot. I think it shows that it has shifted in a good way,” she told The Independent last week.

For his part, Fetterman has consistently rejected the idea that he is some kind of savior to Braddock. His pitch has always been that he will try.

“I never said I could save Braddock,” Fetterman told the Washington Post in 2018. “It’s not about me. It was never even just about Braddock. It was a metaphor. Places like this matter.”

The Fetterman campaign declined The Independent’s request for comment on this story.