You think of most of the great bass players in rock’n’roll – John Paul Jones, John Entwistle, Bill Wyman – and with very few exceptions, the archetype is of ‘the quiet one’; the sturdy rhythmic pillar around which the more flamboyant members of the group (in other words, the singer and the guitarist) can basically show off.

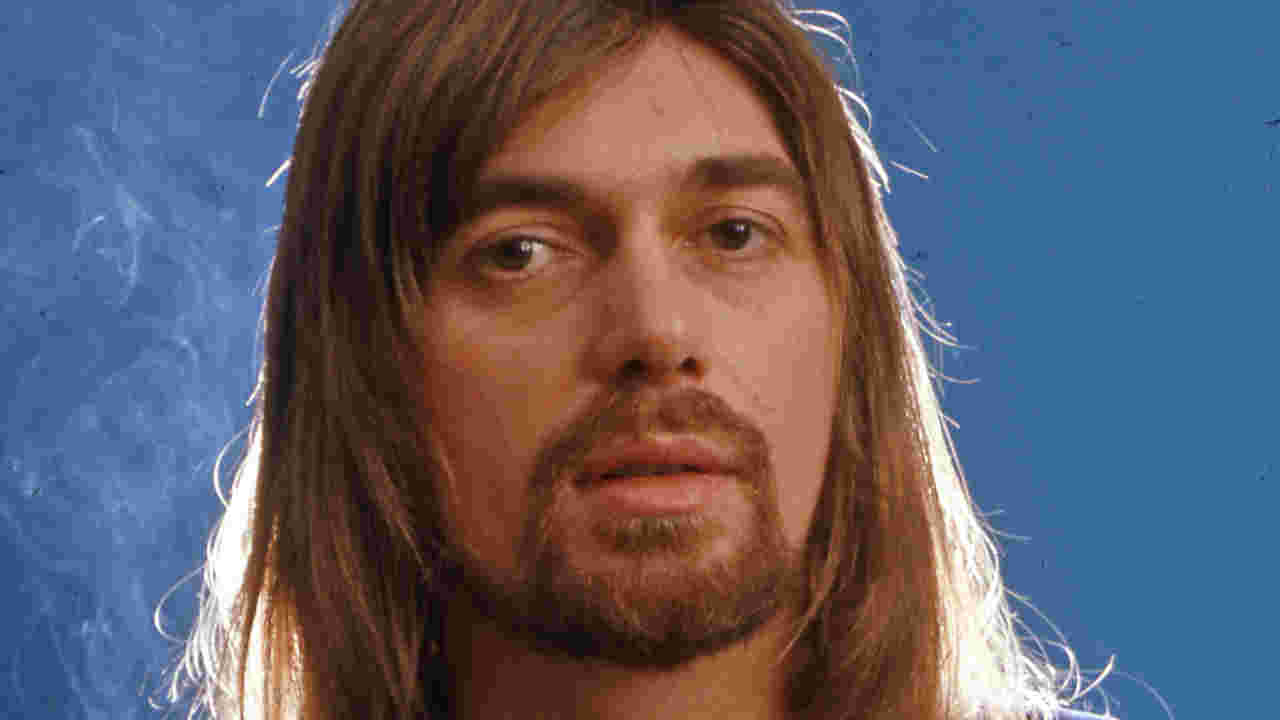

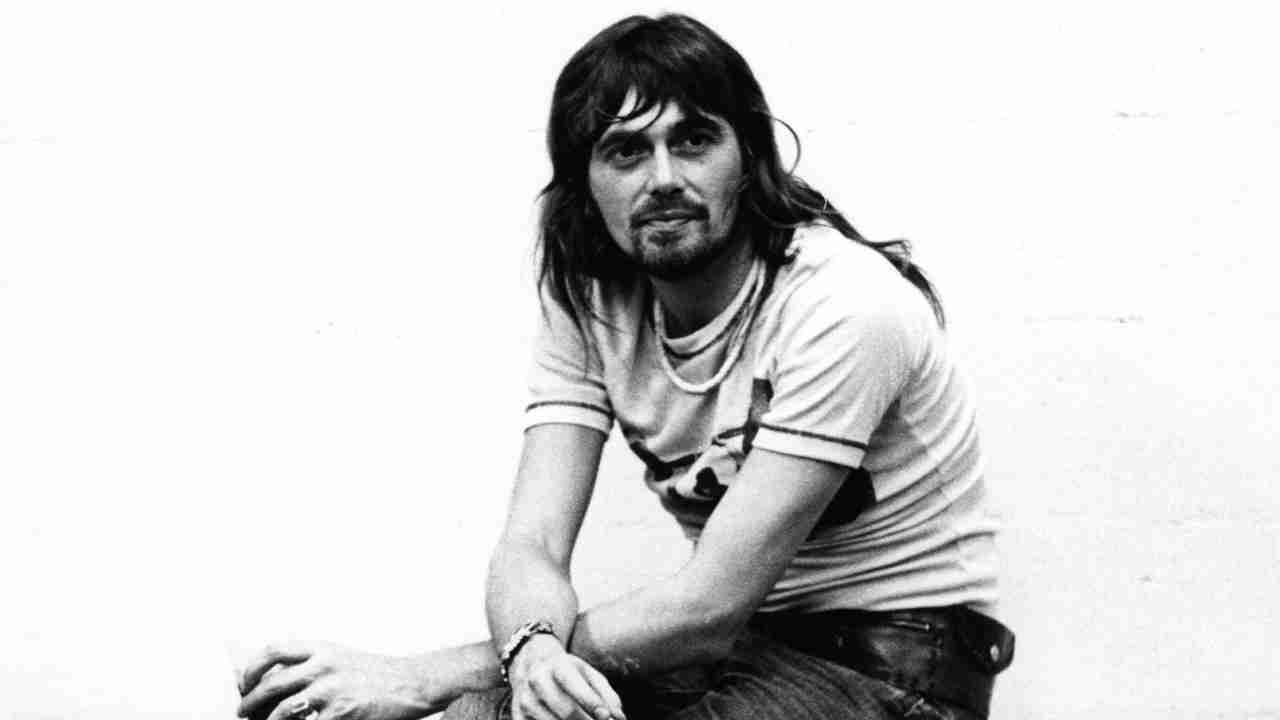

Then you come to Bad Company bassist Boz Burrell, who may have appeared, on the surface at least, to have conformed to this stereotype – the cool cat in the cowboy hat, smiling serenely behind his fretless bass – but who could not possibly have answered to the description of ‘the quiet one’. Certainly not in any sense that anyone who ever knew him might recognise.

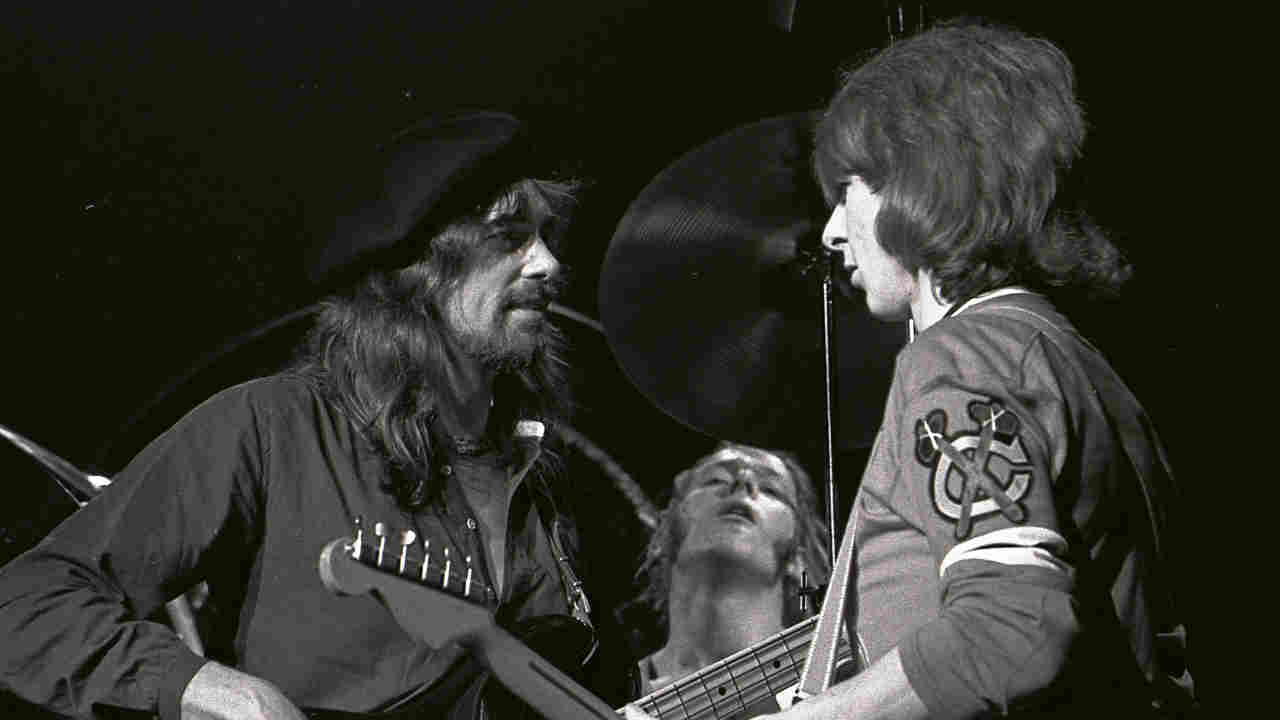

“I liked him straight away,” says Bad Company guitarist Mick Ralphs, “because he wasn’t quiet at all. He spoke up. And he made you laugh. And he was just such fun to have around. You couldn’t really ignore Boz, that’s for sure.”

None of which should be confused with the suggestion that Boz – as the last member to join Bad Company – was there simply to make up the numbers. As his godson, Mike Patto Junior – himself a respected keyboardist, bassist and multi-instrumentalist – says now: “As far as a musician goes, which no one ever talks about, Boz smashed most bass players. And he kept getting better too.”

“He was definitely a perfectionist,” chuckles Simon Kirke. “At least, I think that’s the word for it. When we used to record, I used to perform every take as though it was my last. More than two and I’d be ready to collapse. Then just as I’d given absolutely everything, falling off my drum stool, Boz would shrug and go, ‘Let’s try that again, shall we?’ I’d be, ‘Noooo!’”

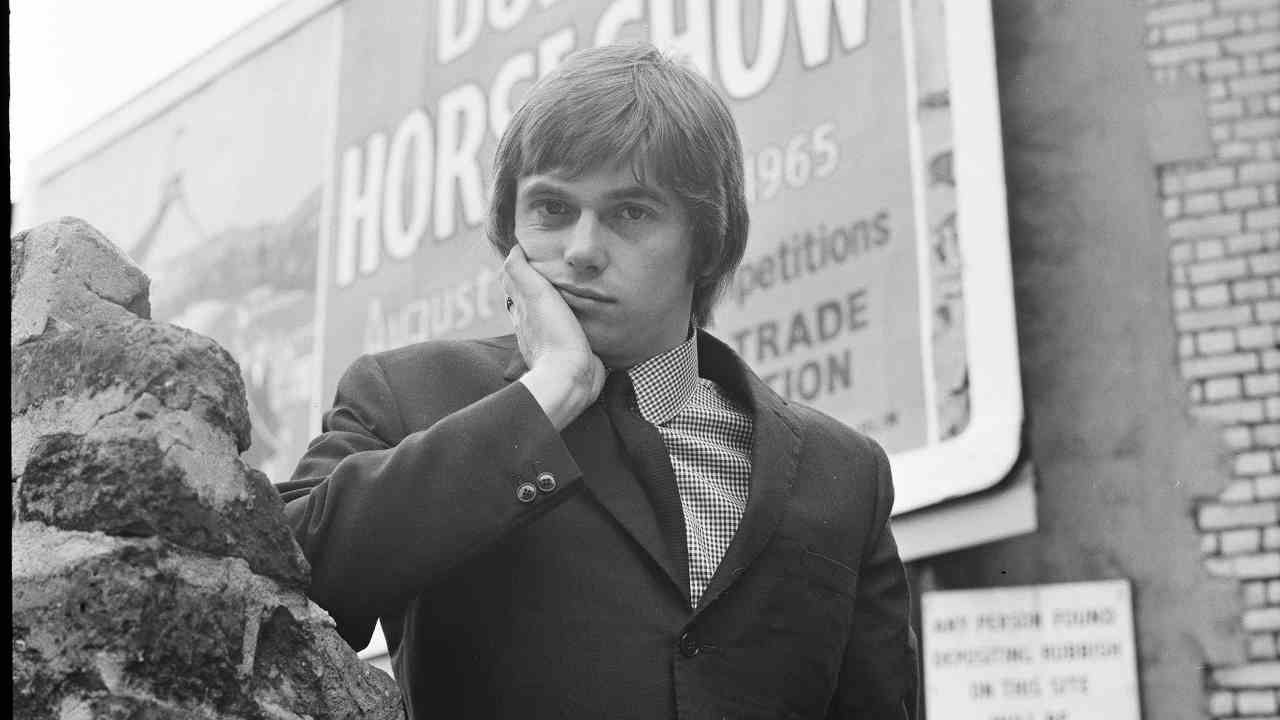

Raymond Burrell was born in Holbeach, Lincolnshire, in August 1946. His earliest musical tastes reflected his later professional penchant for untamable joy (Fats Waller’s Ain’t Misbehavin’ was a particular boyhood fave) and utter seriousness (jazz bassist Charles Mingus became a lifelong influence). He started out, though, in a string of Norfolk-based teen groups as a singer, not a bassist. It was his passion for R&B that landed him his first professional gig in London as the singer-guitarist with Lombard & the Tea Time Four, which featured future Faces and Rolling Stones keyboardist Ian McLagan.

In a prophetic precursor of the sort of musical schism that would come to characterise his later career, not least in Bad Company, Burrell and McLagan split when Boz decided to go in a more jazz direction, while McLagan followed his heartfelt love of the blues. The result was Boz And The Boz People, a little-known club outfit that at least pleased Boz, and which marked the start of a fairly nomadic musical career.

There were several Boz People singles released on EMI’s Columbia label, but none received mainstream attention. In 1968, Boz recorded solo cover versions of Bob Dylan’s I Shall Be Released and The Doors’ Light My Fire, both of which featured future Deep Purple guitarist Ritchie Blackmore. Again, neither was a hit.

It was also around this time that Boz met Robert Fripp when both men took part in keyboard genius Keith Tippett’s Centipede – an experimental amalgam of jazz and progressive rock that truly went where no sane musician had gone before. Fripp was suitably impressed and in 1970, when he needed a new vocalist for his own group, King Crimson, it was to the easy-going jazz hog Boz that he turned. However, when the proposed bass player, Rick Kemp, changed his mind about joining the band, Fripp offered to teach Boz to play bass.

“Fripp is obviously a massively respected musician, but in those days he ran a very, very abstract ship,” says Patto Junior. “Boz had to know the material really well. Fortunately, his big hero was Charlie Mingus, and those serious jazz musicians make all of the rock’n’roll guys look like pussies.”

Boz only made one studio album with King Crimson – Islands in 1971 – but it was enough to re-establish his name within the rock fraternity. When that line-up of Crimson broke up in 1972, Boz was in demand, playing on Peter Sinfield’s solo album Still; working with other ex-Crimson members in the short-lived but critically applauded Alexis Korner offshoot Snape; and appearing with former Family members Roger Chapman and Charlie Whitney in their new project, Streetwalkers.

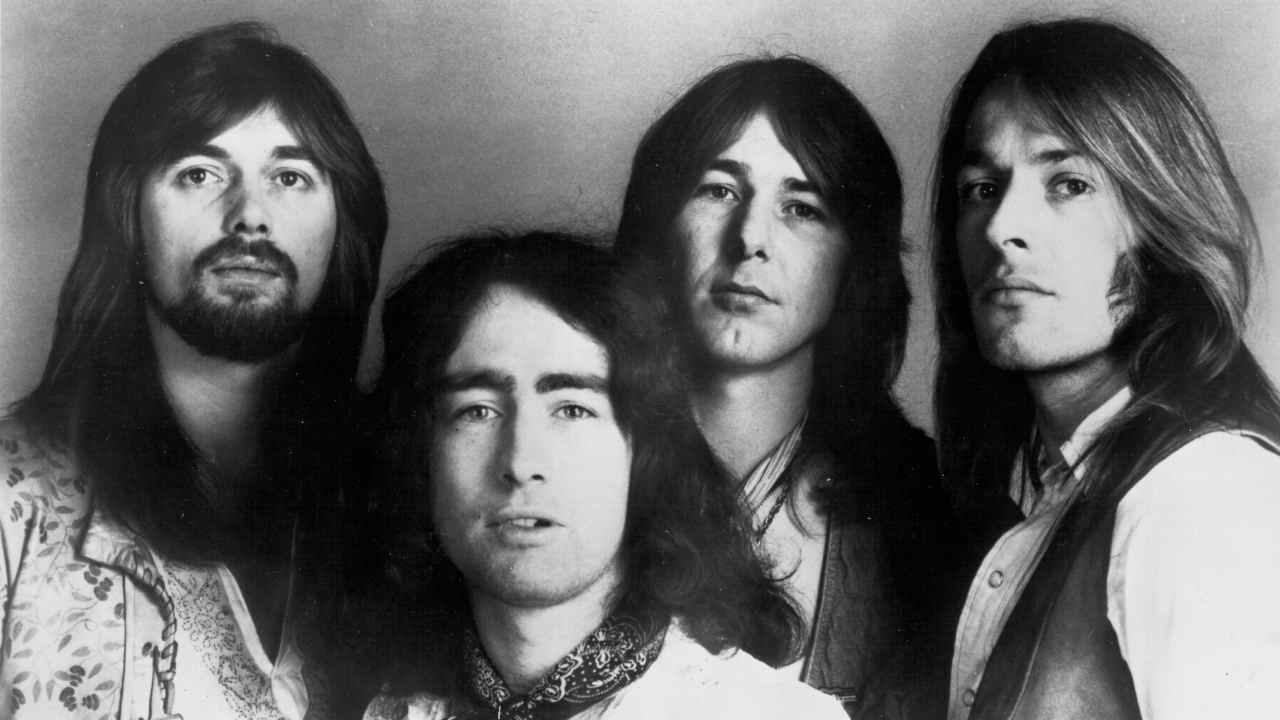

In the summer of 1973, Boz heard that ex-Free singer Paul Rodgers and former Mott The Hoople guitarist Mick Ralphs were looking for a bass player to form a new band. In his own words, Boz “thought it might be interesting” and so “went along to see what they were up to”. By then, Rodgers and Ralphs had been joined by Kirke and had already auditioned over a dozen bass players. “We had nearly given up when Boz wandered in one day,” recalls Ralphs.

Behind that amiable exterior lay a musician approaching his 30s who was determined to make the most of the opportunity offered by this potential ‘supergroup’. Never entirely satisfied – musically, at least – he later complained: “I sometimes hear Can’t Get Enough and think I should never have played a fretless bass on that. The pitch is so out of tune.”

Inspired by The Band’s Rick Danko, who had played fretless bass on the 1971 album Cahoots, Boz was determined to make it work. Out of pitch or not, he was immediately cited by other bassists as being one of the most melodic players of all.

Mike Patto Junior, whose namesake father had been one of Boz’s closest friends in the 60s and 70s (“After dad died in the 70s, Boz took me under his wing”), recalls, “Everyone who knew bass always commented on how good Boz’s left-hand technique was, insofar as he always had extremely arched fingers and he would always play on his fingertips. Just as a cellist would do, or someone like Jaco Pastorius would do.”

However, at the time of Bad Company’s greatest success, Boz had also built quite a reputation for his offstage antics too. Another close friend from Boz’s heyday is Tim Hinkley, the legendary keyboardist who made his name playing with some of the most cherished artists of the era, such as Al Stewart, Alvin Lee and Humble Pie, and who would also play keyboards on Bad Company’s Run With The Pack and Desolation Angels albums.Tim has so many memories of Boz, “I could seriously write a book on them!” he chortles now from his home in Nashville.

“We had similar tastes. We all loved jazz and blues but it wasn’t until we all ended up in this hotel called the Madison Hotel in Paddington that we got to know each other well. It was this strange place where you could rent a room with four beds in it and you paid five pounds sixpence a week, and they changed the linen once a week. There was a phone outside in the hallway, just sat on the floor. You couldn’t dial out on it but you could get calls in.

“I was in a room with Boz, Mike Patto and a drummer called Barry Wilson, and we shared that room for about six months. I remember the phone ringing one day, out in the hallway. No one got up before about one in the afternoon so I stumbled out into the hallway and this voice barks, ‘Where’s Boz?’ ‘He’s in bed asleep!’ The voice goes, ‘Fuck! He’s supposed to be at the TV studios!’ Somehow his manager had got him wangled to sing Mel Tormé’s Comin’ Home Baby with the Ted Heath Orchestra. And he did it. We all watched him, in the lounge downstairs, on the little TV, going, ‘Hey, that’s our mate, Boz!’

“At one point I remember Boz had a quartet but he just wasn’t happy and around this time he said to me, ‘I’ve been hanging out with Keith Moon. He wants me to go to a gig ’cos they want to get rid of Roger Daltrey.’ ‘You’re gonna sing with The Who?’ He shrugged and said, ‘Well, I’ll go and see.’ So after he’d been and done it, we’re asking how it went and he goes, ‘Oh man, those guys are mental! They fight and there’s fisticuffs and Roger laid out Pete!’”

Hinkley reckons that when Boz got the gig with King Crimson, “He hated it! It wasn’t his music; it was what we always called in those days ‘public school rock’. Anyway, he got the job singing and came around to see me and said, ‘Aw man, I don’t know if I can do it.’ I said, ‘Well, it’s a gig and they’ve got tours lined up.’ He said, ‘It’s really weird singing the stuff.’ That’s when Pete Sinfield wrote the lyrics and they were cosmic. So anyway, they were looking for a bass player and he came and asked me what I thought.”

As Hinkley points out, “Boz was a very accomplished jazz guitar player and he had all the harmonic sense already,” refuting later claims that Fripp taught Boz the bass from the ground up. “Robert may have – and probably did – show him all the changes and the tricky bits in the King Crimson songs, but Boz, that’s what made him such a great singer, ’cos he had great harmonic sense. He knew what an A minor 7th flat 5 was, so instead of, say, playing a B over it, he knew what that chord was and what notes he could play over it.

“So he played bass with King Crimson, mainly because he wanted a diversion, and so that band – Robert Fripp, Ian Wallace, Mel Collins and Boz – it was three against one. They’d rush out on stage and start playing before Fripp had even had time to get his guitar on! And they were great because it was such a jazz-influenced band. Listen to some of the live tapes – Earthbound, I think, was an album that came out and it had hardly anything to do with the original King Crimson. They improvised the lot because Mel was a great player and Ian was a great jazz drummer.”

It was around this time that Boz and Hinkley ended up playing together on a session for legendary American R&B singer Esther Phillips. “One of our favourite albums was Esther Phillips’ From A Whisper To A Scream. We loved all those New York players, and she was doing a gig at Ronnie Scott’s so we went down. It was her last night and it was terrible! ’Cos the band was a pick-up band of English musicians who had no concept of where she was coming from. We went and met her backstage and Boz said, ‘Hey, if ever you need a decent band, give us a call.’ So we went home and about two in the morning we were sitting around playing records and the phone rang and it was Esther. She said, ‘Are you guys available to do some sessions? I’m coming over!’”

The home-made demos they recorded that night led to Boz and Hinkley flying to New York to make an album with the singer. “Poor Boz, been playing bass for a couple of years and he’s like, ‘Whoa, we’ve done it now!’ and it was great. It was a hell of an experience. It choked us a bit; we didn’t play that well. We didn’t play anywhere near as good as we did on the demos but it was sort of like a little bit ‘in at the deep end’ kind of thing. But it was good for Boz. We came back from that and finally Crimson split up and he didn’t know what to do.”

A year later, when he joined Bad Company, Hinkley recalls, “Boz inviting me and [future Whitesnake guitarist] Micky Moody to some Bad Company party on a barge on the Thames.”

Clearly, his old mucker had hit the big time.

“There’s a great story about New Orleans that Peter Grant told me,” says Hinkley. “Peter had a photographic memory. So they’re in New Orleans and after their show they all go in the French Quarter. And this was in the days when everyone did everything there was – blow, smoking dope, drinking like fish. They’re in this bar and [Grant] and a couple of the crew are sitting at this table and Boz is up at the bar. There’s this long list of drinks behind the bar and the deal was, if you got to the bottom of it, you got some sort of prize.

“So Boz is wading his way through this list. Now Boz could be… not stroppy, not really nasty, but he could attract the aggro a little bit. So they see this guy pull a cosh from his pocket. He was gonna whack Boz. Well, that was a red rag to a bull. Peter Grant, although he was six foot six and hundreds of pounds, could move like a rocket. So they leapt up and all of a sudden this Wild West fight breaks out. Boz was so drunk he just looked around, oblivious, saw this side door exit and just stumbled out and went back to the hotel! The rest of ’em got arrested and they’re all lined up against the wall outside. They’re all battered and bruised, people with broken noses – it was a real heavy-duty punch-up. Peter Grant’s got his hands up on the wall and says to the cop, ‘Officer, if you look inside my jacket pocket, you’ll find my New York Sheriff’s badge.’ The cop says, ‘I don’t give a shit if you’re the President of the United States ’cos down here we make our own laws.’ So they get shoved in this black-and-white, him and [Bad Company tour manager] Clive Coulson, handcuffed and on the way to jail.

“Peter whispers to Clive, ‘Can you get your hand in my pocket? In the little ticket pocket there’s a gram of coke.’ So he fishes it out and stuffs it down behind the seat. Anyway, they get out of jail and I don’t think any of Peter’s bands ever went back to New Orleans for a very long time. Peter said, ‘To this day, there’s a black-and-white riding around New Orleans with a gram of my coke!’ But that was so typical of Boz – created a huge fracas and then just wandered off, blissfully ignorant!”

By the mid-70s, Boz’s reputation as the Mr Party Hearty of Bad Company was well established. However, as Patto Junior points out, in those days, “All these substances were being used to expand people’s minds, to communicate ideas. They were being put to a purpose, rather than being used just for hedonism. And that was how Boz used them too – as a tool for his music, not just for indulgence.” Then he adds with a chuckle: “Boz was very, very partial to vodka. That was his tipple. He would always have – always – in his bass case, half a bottle of Smirnoff.”

Success had little effect on him. “When he made his money, everyone’s buying mansions in the country, but Boz buys a house in Ladbroke Grove!” Patto Junior says. “He loved the Grove, did Boz. And then there were the famous fishing trips we used to go on, down at Dungeness in Kent. We used to go beach fishing, right out on the shingle beach there. Boz loved it ’cos most of the guys used to leave their cars up in the car park – you couldn’t drive out down to the shingle beach. But he had a Range Rover. So there’s all these other guys at the water’s edge, huddling with their thermals and their big waterproof coats and kit and everything, just to fish for a couple of hours. And Boz would ride right up and smack! Sometimes they’d last for days, those fishing trips. They were wild.

“You know, he was a great guy, Boz, and I loved him dearly. I miss him to this day. There was a beautiful synergy of being incredibly funny, an amazing raconteur, a great storyteller, never took himself seriously at all – except for when it came to music. When it came to music, Boz was super serious about it. Always super serious about what’s happening and what’s not happening, what’s good and what’s not about every single facet of the music.”

Serious enough to know a great tune when he heard it. While recording Run With The Pack, Bad Company became aware there wasn’t an obvious single to release, and so Boz suggested the Leiber and Stoller-penned Coasters classic Young Blood – and Bad Company had another Top 20 US hit. As Rodgers later recalled, “Young Blood was Boz’s idea, and a really good one. It was such a great stage number and the audiences loved us doing that ‘Look-a there, look-a there, look-a there’ bit. It was a big single in America and [kept us] part of an exclusive set in the States, travelling by private jet and limousines.”

Of course, it was the fractious relationship between Rodgers and Boz that heralded the end of the original Bad Company line-up. But by then, as Ralphs acknowledges, “the cracks had already started to appear”.

At that point, Boz was keeping to himself on the road. Patto Junior recalls: “When Boz was on tour with Bad Company in the States or anywhere around the world, as soon as the gig was over, the guys were off and doing the rock’n’roll thing. But Boz was straight in a cab and he would just hit the local jazz clubs. As a result, he knew loads of the real jazz heavyweights.

“He got in a cab once in New York and started talking to the driver. He said, ‘Yeah, man, I play bass.’ Boz was like, ‘Yeah, so do I. What’s your name, man?’ He said, ‘Ron Carter.’ [A legendary jazz Hall Of Famer who played on nearly 3,000 famous jazz albums. Boz was bowled over.] He said, ‘I’ve got every record you ever made!’”

By the mid-80s, he’d had enough. When the band eventually reconvened with Brian Howe on vocals, Boz declined to join them. At their shows, “The cherry bombs were flying,” he explained, “and I thought, ‘Jesus Christ, if this is music… it didn’t seem worth it to me. I mean, how much money do you need to live? Not only that, the old body was also giving out.”

Instead, Boz kept himself busy with a string of different musical projects: working with another old mate, Alvin Lee, as part of his Best Of British Blues tour; fronting his own jazz line-ups that would gig around London; playing with his godson Mike; and working in a big jazz band with renowned Scottish vocalist Tam White. For a time, he even hooked up with 60s singer, actor and comedian Kenny Lynch.

“I met Boz on Ready, Steady, Go! in the 1960s,” said Lynch, “He had some beautiful instruments and, like me, he preferred the wooden ones to the red-paint jobs. He was always very enthusiastic about his music and he was always saying, ‘I’ve got a better idea.’ It could drive me mad as I didn’t need to be backed by Charlie Mingus. But he was always right.”

Boz also got married for the second time, to Cathy, a feisty young woman nearly 15 years his junior. They’d met during a Bad Company recording session at Ridge Farm Studios in the late 70s. “He was a cheeky chap,” she says now. “He straightened my stockings, the line down the back, that’s the first thing I remember. He just knelt down on one knee and said, ‘Oh, let me straighten that out for you.’ Dirty little bugger!”

The two discovered they had a mutual interest in jazz. “I wasn’t really into Bad Company, as music. I was more into jazz. That’s how Boz and I clicked – we were both jazz fans. Monk, Mingus, Miles Davis. Boz got me really educated in all of that.”

By the time they were married a few years later, Boz’s time in Bad Company was all but over. “They hadn’t broken up – they just didn’t bother recording any more. It was that time. I think they all wanted a rest from touring. It does make you ill.”

Patto Junior says, “Anyone as smart as Boz couldn’t overlook the Spinal Tap [connotations]. They can’t go, ‘Stonehenge? Is that really what we’re doing tonight?’ Boz can’t sit there listening to that while reading George Russell’s Lydian Chromatic Concept Of Tonal Organisation. There’s nothing wrong with R&B, but if you’re going to play R&B, it has to be done with conviction. Once it becomes faking the funk, man, that was just not his thing. Boz saw rock as a really great, funky, funny style of music, but the moment it became padded shoulders and hairspray and make-up, it’s bullshit.”

Cathy, who accompanied Boz on his final, fateful ‘comeback’ tour with Bad Company in 1999, describes the experience as “very stressful. Obviously not having toured for so many years, it was hard work as well. Some bits were great fun but the other bits weren’t.”

She adds: “The main thing was there were two people that didn’t drink or smoke [Rodgers and Kirke], and two people that did drink and smoke [Boz and Ralphs], and you can’t have them on the same bus, obviously. Mick and Boz got on like a house on fire, those two. And Simon’s a good egg. But you just couldn’t mix non‑smoker, non-drinkers with smoker-drinkers. It was a fact. You can’t do that on long journeys.”

Boz would never tour with Bad Company again. He and Cathy lived in England for a while, then later went to live in Spain. “Every day he’d pick up the bass,” she says. “There was usually a couple round the bed. Choose one and just start playing, constantly. Practising for hours. Then playing along to anything that came on the telly. And then swearing at them for cutting it. You know, when they splice music to make it fit for an advert? He got really angry about all of that. He’d have his kettle with him, drinking black tea. He’d stopped having milk because it would go off in the bedroom. That’s how laid-back he was. Earl Grey, mind you. It had to be Earl Grey.”

It sounds like he didn’t leave the bedroom. “Not a lot. Unless he had a gig. In the summertime he’d be out like a lion, ’cos he was a Leo, sunning himself in the garden. We had a train track; a nought-gauge train track. So I’d make the tea from the kitchen, then I’d send it off over to him.

“He got into model airplane flying. We hooked up with [session drummer] Henry Spinetti and he was a member of Cranleigh Model Flying Club, so he dragged us down there. I’d build them and Boz would crash them, and I’d go and pick them up in the next field, covered in cow manure, take it home in a plastic bag and rebuild the buggers. I was the first lady member of the Cranleigh Model Flying Club. Those were the days!

“After that it was stunt kites. Three-metre kites – huge airfoil kites you stack on top of each other and you can do all these stunts with them. I’ve still got the buggy on the top of my shed that we used. Boz [would be] pulled along the beach. You’d just hear Boz screaming, going down the beach, ‘I can’t stop the fucker!’ Then you’d hear this almighty crunch and that would be Boz and the buggy in bits. I was dragged all round the country with these kites. Sitting there freezing with the windbreak around me, just waiting for the scream…”

They had quite a life together. “Yeah, we did. We were joined at the hip. I’m a garden designer and he’d come out and dig holes and smash things up for me. That was his favourite thing. Man stuff. So whenever he came off his tours, it was into the garden or practising or playing silly buggers. That’s how laid-back he was.”

Cathy recalls how when Boz died, in September 2006, “I was doing his belated 60th birthday party and we had a whole load of people coming and flying over to Spain. He was playing Alvin’s [Lee’s] guitar, doing a little bit of practice with some friends, and he just fell off the chair. He was playing Autumn Leaves, his favourite tune.”

She pauses, then adds: “People had just got off their flights and stuff like that and it was going to be a bit of a humdinger. But he didn’t quite make the party.”

His cause of death was reported at the time as being a heart attack, but Cathy says, “I think it was probably an aneurysm or an embolism, something like that. Because he’d just had a little operation on his arteries in his thighs. They were all clogging up, and all that jumping about… he probably shouldn’t have been doing that. I don’t think it was a heart attack.”

She adds with a wry chuckle: “He was something like 60, six weeks and six days. I think he made it to the seventh day, so he wasn’t the devil.”

Atlantic Records’ founder Ahmet Ertegun issued the following statement when Boz’s death was made public: “Boz was a great musician and a great human being. Atlantic began its long relationship with Boz when he was a member of King Crimson in the early 1970s, and so we were thrilled when he was recruited to become a founding member of Bad Company. The band went on to make a string of great records, and they were one of the most important and successful groups in the history of Atlantic. Steeped in jazz and blues, Boz’s rock-solid playing was the anchor of the band’s sound. We will miss him terribly, but his many fans will never forget all that he contributed to the history of rock’n’roll.”

Boz’s godson, Mike Patto Junior, insists that Boz died just as he had lived: by his own rules. “He knew he was going. He’d had a big scare about a year before and ended up in hospital. And he’d made up his mind how he wanted it to happen. He already had the pacemaker in, the veins in the legs that were going wrong. He had blood pressure issues. I mean, man, he had, like, six very serious medical conditions. And he was staring it straight in the face. It was coming for him and Boz knew absolutely that he was going to go. And this was just going to be his body falling apart on him.

“And he’s got two choices. And he chose: fuck it, I’m going the quick road. I’m not gonna go out the long, protracted, lying in bed for fucking years on end, eking it out till the end. He chose: I’m gonna go rave my heart out, and he did.

“Boz came out of hospital, got his musical chops back, back on his feet. Bam! Back on the chisel [cocaine], back on the booze. Back on everything you can imagine. And he rocked out. That last six months of his life, he had a fucking party! And that’s what he did. And that was a conscious decision on his part. It wasn’t hedonism, it wasn’t laziness, it wasn’t because he just couldn’t be bothered to get healthy again. It was because he knew his body had fallen apart, to a state that there was no coming back from. So he decided to go out that way.

“What happened was, Tam White, who was our long‑time collaborator and a massively talented musician and singer, was learning guitar and he was getting really good at it. Boz is sitting at the table with him, listening to him playing, and he’s halfway through this standard [Autumn Leaves] and Tam plays the wrong chord. Boz went, “No, you cunt. That’s a half‑diminished!” And he grabbed the guitar out of his hands and played a half-diminished – and then collapsed on the floor and died.”

But, says Patto, that’s not how those who knew Boz will remember him. Instead, it will be this way: “Boz was a really genuine, warm, loving, passionate, funny dude that would light up a room as soon as he walked in. As soon as Boz walked into any studio or gig or wherever, everyone would have a great time. Anyone who wants to know, you can tell them: that’s who he was.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Bad Company, March 2014