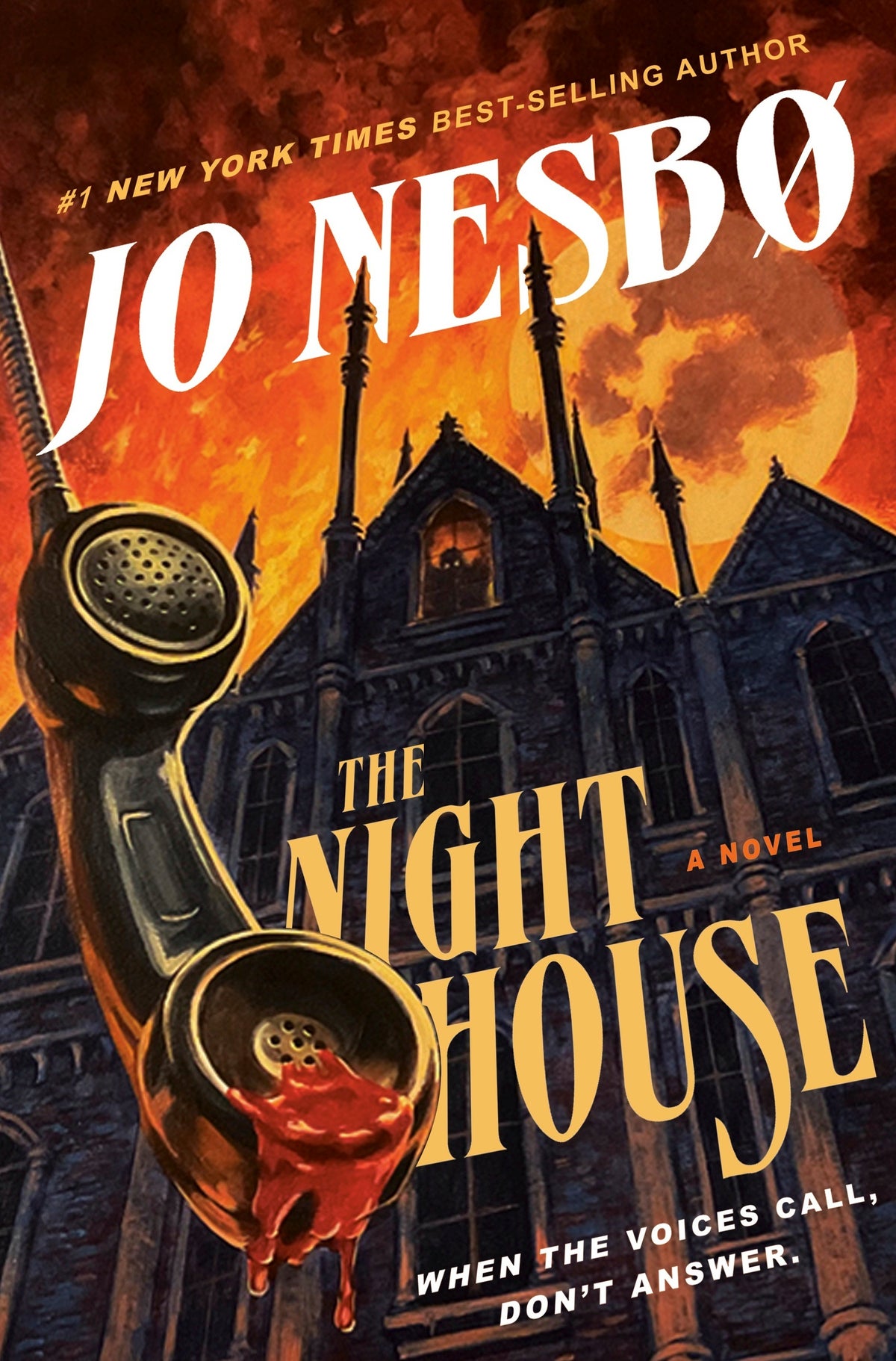

Jo Nesbø, the Norwegian author best known for his 13-book crime series starring Harry Hole (“The Snowman” was made into a 2017 movie with Michael Fassbender), is out with something completely different.

“The Night House” begins like something from the mind of H.P. Lovecraft, as a young, bullying boy in the English countryside dares a classmate to make a prank call from a phone booth. By page eight, the classmate’s ear is “stuck to the bloody, perforated listening end,” and the phone is making slurping sounds as it liquifies Tom and sucks him into oblivion. Suddenly Richard, the young bully, is a chief suspect in Tom’s disappearance.

When another classmate mysteriously disappears after spending time with Richard, Richard is sent to the Rorrim Correctional Facility for Young People while authorities investigate. We learn bits and pieces of his back story in the next 100 or so pages — his parents died in a London fire when he was 14 and he’s now living with relatives in the U.K. — which end with him breaking out of the facility as he tries to save the life of a third classmate who is possessed by whatever evil lurks on the other side of that phone line.

And then at a little over the halfway mark of this slim horror novel, Nesbø begins “Part Two” and readers are forced to rethink everything they just read. It’s a remarkable about-face, but not altogether surprising. Narrators aren’t always reliable, after all, and telephones that eat boys are the stuff of a vivid imagination. How things piece together for the remainder of the book shouldn’t be spoiled, but suffice it to say “The Night House” really isn’t a classic who-done-it horror novel, but a story of one traumatized young man’s search for meaning in the wake of a personal tragedy. Or as one of the characters Richard meets in his journey tells him: “There’s hope for you. … That you’ll find yourself. Your real self. The nice, kind boy you’re trying to hide.”

After readers turn the final page of the book, it’s fun going back and picking up all the foreshadowing, some of which seems heavy-handed in hindsight, but goes barely noticed on first read. Nesbø inserts some references to Kafka and “The Lord of the Flies,” even “Night of the Living Dead,” which by the end of the novel function like that final scene in the 1995 film “The Usual Suspects,” as Verbal Kint reveals how he created the legend of Keyser Söze.