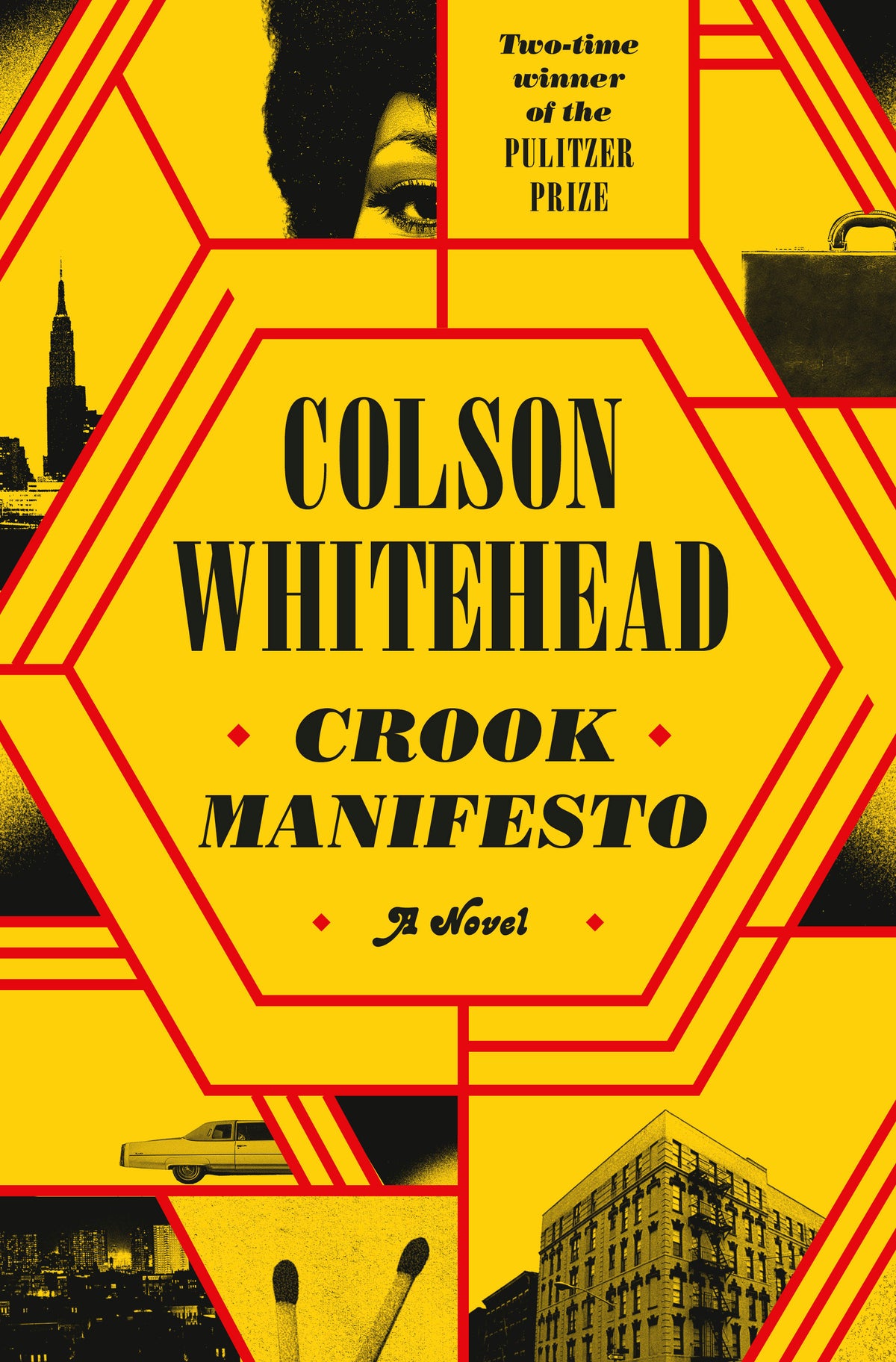

“Crook Manifesto” by Colson Whitehead (Doubleday)

In his bestselling 2021 crime novel “Harlem Shuffle,” Colson Whitehead introduced the complicated character of Ray Carney, a Black furniture store owner and small-time fence clawing his way into the middle class while resisting the urge to follow in the footsteps of his thuggish father. That novel played out in Harlem during the civil rights struggles of the early 1960s, and the city itself was a major character.

Now he’s written a sequel. When “Crook Manifesto” opens, it is 1971, Carney has been on the straight and narrow for four years, and civic harmony is in short supply, “like honest mayors and playgrounds free of nodding junkies and broken bottles.”

Carney’s desire to score impossible-to-get Jackson 5 tickets for his increasingly aloof teenage daughter prompts him to seek out the corrupt cop and fixer he used to do business with — and all hell breaks loose. With Carney back in the game, Whitehead proceeds to show us “the invisible barrier that separated his city from the white city” in a decade when the Bronx was burning and the Daily News blared “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”

The novel is broken into three parts loosely connected through the storylines of Carney, his family, and a handful of other characters, including Pepper, a hardcore criminal who is surprisingly endearing. The second section, set in 1973, revolves around the shooting of a blaxploitation movie on location in Harlem, including at Carney’s furniture store. The third part takes place in 1976, when the son of one of Carney’s tenants is severely injured in an arson fire and Carney can’t work up much enthusiasm for the nation’s bicentennial celebrations. As a store owner, he is expected to jump on the patriotic advertising bandwagon — “a dome of red, white, and blue smog” — but the only slogan about America that sounds right to him is “200 years of getting away with it.”

As he did in “Harlem Shuffle,” Whitehead mixes noir crime tropes and social history to present a slant, cynical view of New York as a thoroughly rotten Big Apple, only occasionally redeemed by individual acts of love, loyalty and kindness. Whenever Carney’s wife wants something that’s going to cost serious money, and Carney realizes he doesn’t have it, he says to himself, “What else was an ongoing criminal enterprise complicated by periodic violence for, but to make your wife happy?”

Whitehead’s sly sense of humor and encyclopedic knowledge of the city make “Crook Manifesto” an entertaining read, but as incident after incident piles up, you just want it to be over.