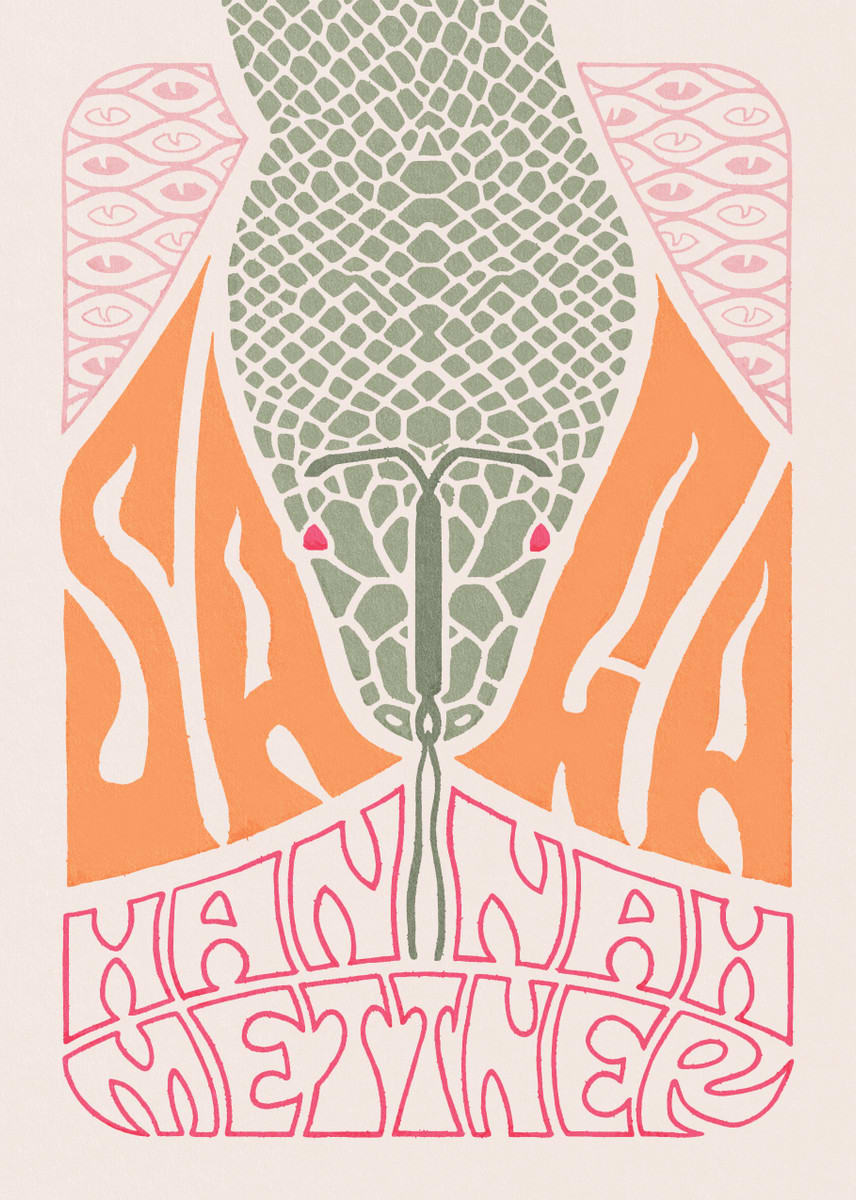

The best book of poetry of 2023 (so far) is electric with sex and reads like a MILF manifesto

Lately I’ve been thinking about fragrance. Where I write from now, in Michigan, pumpkin spice is the seasonal scent which cometh before the fall. Kerbside lavender smells wrong here – less the familiar grandma-sweetness of colonial garden varietals in the Aro Valley, more a stringently rangy herb that reminds me of my own strangeness in these streets. Before I flew my girlfriend gave me the last of her own perfume. It’s an indie Of Body concoction wrung from lavender and animals that almost chokes me with yearning on each spritz, lingering carnal as skin hunger on my wrists. And I’ve mostly been reading Fragrantica cologne reviews while avoiding the poetry that lured me to this place so far from love.

Olfactory sommeliers have much to say about what happens on the dry-down; what’s left after a perfume’s initial flourish, how it ripens or decays on the skin. It’s a bit like poetry. The test is what sticks with you ages after the first dizzy hit of sound or sentiment.

In Wellington writer Hannah Mettner’s new poetry collection Saga, the signature aromas are thunderhead ozone, prosecco fizz, and citrus with a knife-blade twist; settling to organic base notes of dank cave mildew, powdery library stacks and rich, metallic blood. I’ve now spent good time with Saga, let it cure, and complexities continue to develop. Matters of motherhood and inheritance are central concerns – and while contemporary capitalist polycrisis is an inescapable undertone, love poems that promise gratuitous sex are enjoyably messy as bedsheets.

This book is seductive, possessed of an easy narrative voice whose charming bemusement belies the sense of grisly risk that undergirds the poems. Saga continues the concerns of Mettner’s lauded debut Fully clothed and so forgetful – reckonings of the ungainly body, in love and/or lust; of birthing and having been born. In the chronology of the poems, the narrator’s children are now nearly young adults, and her own mother not getting any younger.

Saga situates its stakes amid links in an ancestral chain. The title poem begins “in the tradition of my people” as history tightens like a knot, exploring Pākehā family lore only by learning that in the language of this country “it is rude to introduce / myself with nothing more than a name”:

My aunt reports that we used to be Vikings, but it is clear that that was a very long time ago. For example all my hobbies are activities that involve sitting and not being killed.

From this outset, Saga meticulously interrogates genetic and cultural heredity. What do you do with a legacy manifested as a dud recipe for pineapple cheesecake? Mettner combs through the pasts and futures carried in familial bodies, life recording its small accidents in the rosy skin of a daughter while mothers grow into their ancestors’ bones. Found ingredients for an alchemical elixir contain generations: “the milky reflux of my babies” and “the hipflask / with my grandmother’s lipstick still on the rim”.

Lipstick becomes a recurring talisman to not just inscribe one’s own feminine visibility but to commune with the dead, iconic lip prints being all that’s left of some women in memoriam. The relative invisibility of women’s lives in the historic record is a critical thread, illuminating patriarchal exercises of power throughout history. In her poem "Anita", the speaker seeks the story behind a hand-me-down name, but finds:

I’m a woman, and women have been thrifty with their appearances on the record…

attending to the context of men, then –

blip, disappearing. Try searching their husbands’

names, the archivist suggests, their sons’.

The only way I find them is through

births, deaths and marriages.

They are not mapped to anything

that doesn’t concern their bodies. I want

to know them in the moonlight – thinking.

Isn’t being known in moonlight all a woman can ask for? Much of this book’s power rests in the good-bad gift of knowing, reaching to a shared education in the conditions of womanhood under patriarchy, into which every initiation seems also an initiation into pain. But a woman who knows too much has long been called a witch.

As Mettner observes, it’s a fine line between curse and verse: “Spells, jokes, poems – same, same. I can be / very articulate for short periods of time, so what?” Saga embraces witchiness – seasoned with alchemy and horoscopes, and elevated by Mettner (slightly prematurely, if I may say so as a friend) taking up the mantle of the hag. Putting the ‘wise’ into ‘wizened crone’, Mettner’s hag messes with the pressures of heteronormative domesticity, but doesn’t underestimate the ongoing riskiness of queerness or hard-won freedoms – counting buried gay icons, wondering if God or His Holy Metal Detectors at the Vatican City will spy a contraceptive IUD.

The more openly polemic poem Three times a cat lady, a character study of a strong independent woman in the wrong century, states the dangers that underpin encounters in the rest of the book:

The Cat Lady has nine lives too. How else do you think she survived the drowning the burning the crimes of passions the rough sex gone wrong the childbirth the hysteria myth the male bias in medical research the walking home alone at night the systematic culling of women over the centuries?

Women’s work is at the core of this collection. This includes the labour of survival – not to mention keeping everyone else alive as well. All the effort of raising kids, keeping friendships buoyant, and variously kindling/tending/snuffing out romances takes place alongside the work of making art (often un- or barely- paid), and the exchange of life-hours at work where the “performance” in your annual review is pretending you have any fucks left to give.

The poem "Beep Test" transplants the rigorous abjection of PE class to the adult workday. Sprinting from beep to beep to the point of collapse like a tormented schoolgirl has somehow become the normative mode of the more sedentary adult body, trying to keep meeting milestones, seeing people, and being tricked into taking annual leave to pick up parents from the airport. But “having a good job means our parents / can measure us against the kids we grew / up with and feel smug that they did a good job / raising us, patting us back into their wallets / like a big wad of cash saved up for later”. Generations are caught in the test, trying to keep each other happy with what measures they have. Mettner keenly captures the way time thins as the zoetrope years flicker past, and there’s never enough of the stuff – no more eternal feral girl summers, no time to play with the kids or check in properly with friends and sisters.

The onslaught of labours in Saga becomes, like a Vatican fresco of the girlies hanging out with babies at their breasts and sandalled feet resting on decapitated heads, “the pastel chaos of womanhood / and behind them, all in black, a neat semicircle of men”. And in this pastel chaos there are opportunities for unfettered enjoyment – the riotous delights of OMG, am I a hedonist?, soft-focused futures attuned to libraries and trees, newfound unselfconsciousness in a butch/bitch era. Mettner says the cat lady “forgets it is a crime not to fulfil / the mandatory requirements of womanhood – / wife and mother, meek and smothered”. But Mettner’s poems of marital fluidity and maternity do not portray a total smothering, and only perhaps a highly selective meekness…

Now to the salacious! At Mettner’s launch I described this book as a MILF manifesto. I stand by it. Saga is electric with sex and explicitly queer, honouring the manifold labours of motherhood while refusing any puritanical sensibility that procreation should be the endpoint of desire. Pleasure is crucial to the book, but not without its attendant anxieties – shame, fear, awkwardness and complexity. I like this. A hint of risk only elevates the sexiness; keeps it honest. If these poems can be taken as confessional, they are also wry in their raunchiness. Permit us our butch moments, our bad man kinks, our charmless body chocolate, our clumsy breakups via text, our awkward encounters with literal-minded exes who shush their own toddlers at the seaside rather than looking for what they see in the water. And while poeticised trysts reaffirm Mettner’s status as a bi icon author, love suffuses the book – complicated love for children, partners, parents, friends, all trying to do right by each other even if we don’t always have the words (O that wonderful quote from a mother “well, you decided to be a poet… didn’t you sign up for a life of misunderstood suffering?”)

Speaking of suffering, in my long-distance volcel era I recently tried to buy a cheaper dupe of my boyfriend’s Maison Margiela. The smell is an initial hit of his smoky chestnut signature that sadly obliterates to nothing on the dry-down - proof that the real lingering thing doesn’t come easy. I’m not shoehorning the sniff test in too hard here either – in one poem “a bad man but my smell / is on you now” recurs a few stanzas later as “‘three months and your spell/ is still on me’, you say, a little afraid / because I like to play / the witch”, the ghost of scent memory crucial to the thesis.

One of the most affecting poems to me was a love letter to Chauvet Cave, the site of some of the world's best preserved Paleolithic art. The poem culminates in a visit to a precise replica of the fragile archaeological site – its exact dimensions and temperature, artworks and humidity. Mettner’s at her very best in moments like this – revealing a cave-dark heart below the witticisms and tender attention that reaches back through human sagas to crave what’s original, primal and unforgiving in us.

Give me true art, real desire, genuine darkness, or nothing. Even if the replicated cavern with its faux-dankness ultimately didn’t trigger the hairs at the narrator’s nape, this book reeks of realness. I’d give it five stars on Fragrantica.

Saga by Hannah Mettner (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $25) is available in bookstores nationwide.