Max Rashbrooke reviews the memoirs of former Labour MP Graham Kelly, one of the last of the party's working-class representatives

Prime Minister Chris Hipkins makes much of his Everyman image as “a boy from the Hutt”, but his mother is a chief researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research and his career has arced smoothly from student politician to political staffer to Labour MP at 30. He's pretty much the the apotheosis of the PMC: the professional-managerial class, a term coined by American writers Barbara and John Ehrenreich to describe private- and public-sector managers, lawyers, accountants, doctors, teachers – exactly the kind of “salaried mental workers” who now dominate New Zealand Parliament, and the Labour Party, even though PMCs comprise just four in 10 people in the wider population.

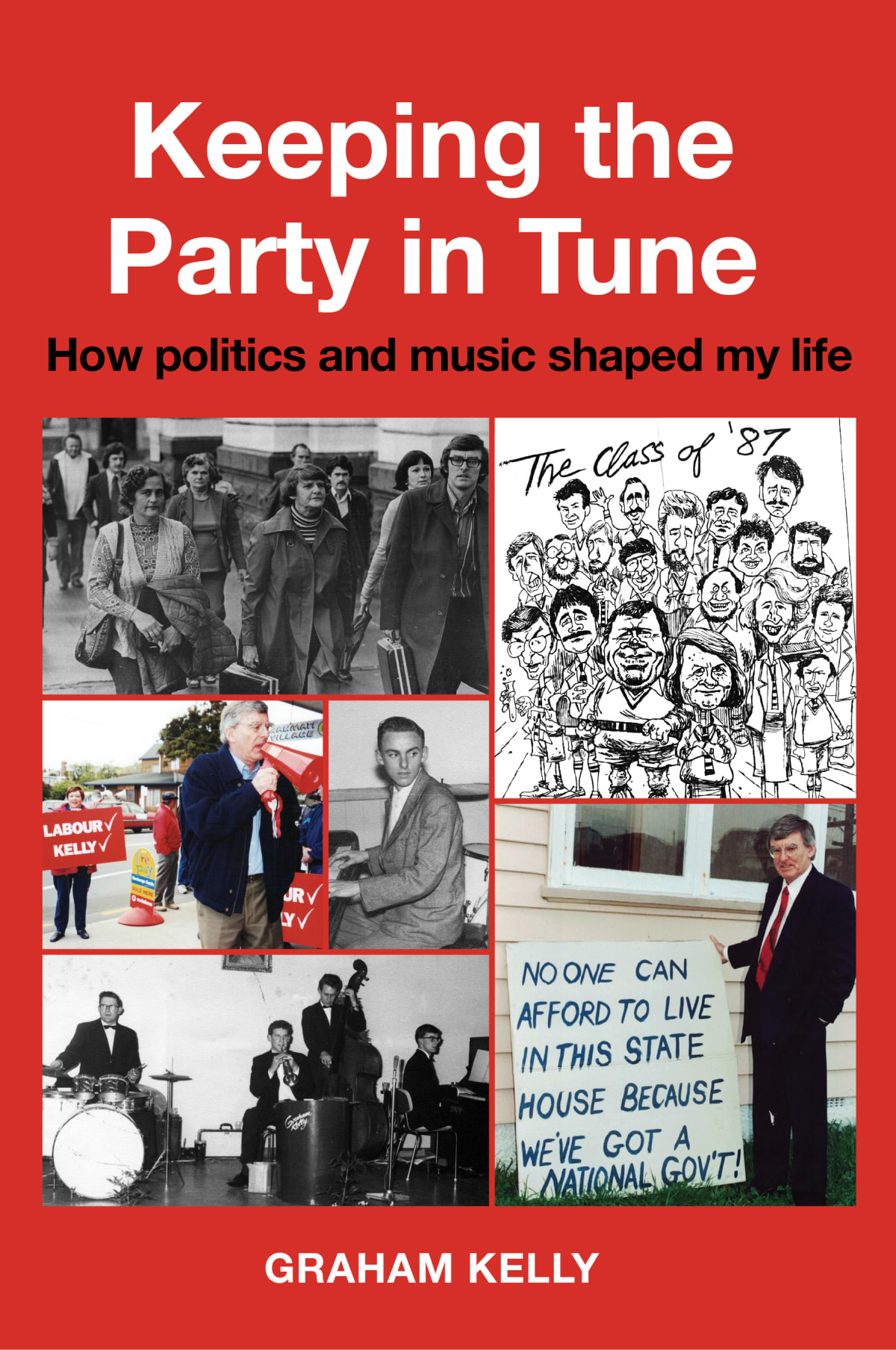

The new self-published memoir by former Labour MP Graham Kelly, Keeping the Party in Tune, invites us to reflect on what these changes have done to the Labour Party, and whether it can still effectively represent the interests of blue-collar workers or indeed those even more marginalised by society.

Right now, virtually no government MP can be said to be blue-collar, even if some, like Labour’s Willie Jackson, had held such jobs earlier in their lives. Research by Victoria University’s Simon Chapple and Peter McKenzie has shown that, in 1972, one MP in five had done blue-collar work – in clerical, service-sector or labouring jobs – immediately before they entered Parliament. The House as a whole was still from a different social stratum than the country at large, 71 percent of whom did such work, but blue-collar workers, and their trade-union representatives, were at least present in politics. The decline in the trade-union movement, Chapple and McKenzie concluded, has been responsible for much of this change in Parliament’s make-up.

This comes through clearly when Kelly writes of his campaign to become Labour’s candidate for the Porirua seat in the 1987 election. An outsider to the electorate, he was derided by a local newspaper, Te Awa Iti, as “the Poodle from Khandallah”. This same newspaper backed another candidate in a style that is sadly lacking in modern politics: “Porirua Dogs Are Real Dogs. They bark, chase cars, growl and bury bones. Poodles from Khandallah do not. They look pretty, sleep comfortably, and eat expensive doggie food. Porirua needs a Real Dog. DANIEL WINSTON. A real dog for real people.”

The dispute has ironic overtones now because Kelly would, by the standards of the modern Labour Party, seem about as real a dog as they come. As he recounts in Keeping the Party in Tune, he got his first job at 17, at the wholesalers AS Patterson and Co on Wellington’s Lower Cuba Street, and was immediately embroiled in a labour dispute. This was 1958; by the next year he was standing for election to the committee of the Clerical Workers’ Union.

In the process, he got an early taste of the rough-and-tumble of left-wing politics. The notorious trade-union operative Fintan Patrick Walsh, president of the Clerical Workers’ Union, had a cunning strategy for making sure members couldn’t vote at meetings: his staff would collect only part of their subscriptions, ensuring they were constantly in arrears and thus ineligible to take part. Walsh also attempted to fix votes by blatantly ‘stacking’ meetings with members of another organisation, the Seamen’s Union, of which he was also president.

Kelly fought his way through these and other underhand tactics to become a key figure in the trade union movement in its 1960s and 70s heyday, a process he recounts in some detail. (There are, it must be said, rather more anecdotes about trade-union administration than is strictly necessary.) And it was on the strength of this work that he stood for the Labour candidacy in Porirua, won selection, and was elected its MP later in 1987.

The memoir is also a reminder of the long shadow cast by the 1980s. For when Kelly enters Parliament, he is immediately thrust into one of the most controversial periods in New Zealand political history. An ostensibly left-wing Labour government is privatising and deregulating the economy at warp speed, in a manner that finance minister Roger Douglas later admits is expressly antidemocratic, deluging opponents with reforms so that they cannot keep up.

Kelly and a small band of fellow left-wingers – the legendary Sonja Davies among them – fight a doomed rearguard action against their own colleagues, in what he labels a “Caucus Civil War”. And they do so at some cost to their own health. One gets stress-induced “boils under his arm and nose”, while another develops permanent flu symptoms. For his own part, Kelly recounts, “My blood pressure went so high that I woke in the night with violent headaches.” Hearing his constituents’ despairing stories later leaves him so upset that his stomach churns and he can hardly eat.

Kelly’s left-wing grouping are quite rightly, and presciently, concerned about the damage Douglas is doing to the country’s social fabric. Tens of thousands of New Zealanders are made redundant with little or no state support to find another job; poverty and inequality start soaring. Corporate raiders make massive profits buying state-owned enterprises for relatively low sums, asset-stripping them and selling them on. Deregulation sets the stage for a laissez-faire health and safety culture that endangers lives and a hands-off style of building regulation that leads straight to leaky homes.

Kelly and colleagues can do little against this onslaught. “I often felt like a leaf in a flooded river being swept downstream,” he writes, “with little or no control about how fast we were moving”. His resistance, however, pays greater dividends once Labour is in opposition post-1990. He leads a civil disobedience campaign of non-payment of National’s user-pays hospital charges, forcing ministers into an embarrassing u-turn. Another telling anecdote concerns Jim Bolger’s brutal policy of requiring impoverished state-housing tenants to pay market rents. After a state-housing family in Kelly’s electorate, no longer able to pay the power bill, switch to using candles and a resultant fire kills two of their children, Kelly is ejected from the parliamentary chamber for demanding that housing minister Murray McCully be charged with manslaughter. Later, during his time in government between 1999 and 2003, he has the satisfaction of partially reversing some of the worst of these reforms.

*

Kelly’s account of this history is, at times, refreshingly idiosyncratic. Most political memoirs are chronological, streamlined to focus on the politics, and faintly self-important. Kelly’s is more in the vein of a loosely connected series of anecdotes culled from a very full life. The title references one of his great passions, music, a subject that generates amusing stories about dancing nuns, unreliable bandmates and gigs gone wrong.

Keeping the Party in Tune is not an excessively polished text: the sentences tend to be plonked down flat on the page. The book also suffers from Kelly’s desire to painstakingly note, and pay tribute to, the minor supportive acts of various colleagues, friends and family members who are clearly valued by him but – alas – of no interest to the general reader.

The memoir does, though, come at an apposite moment. Despite the oceans of ink devoted to its analysis, neither Labour nor the country as a whole has ever quite come to terms with the 1980s revolution. The right tends to laud it uncritically as a necessary destruction of the “Fortress New Zealand” that prime minister Robert Muldoon built, a liberation of entrepreneurial and commercial energy whose resultant swelling of poverty was simply the price paid for this freedom. The left, meanwhile, too often sees it as an inexplicable calamity, a conspiracy foisted on an unsuspecting public and the moment in which “an egalitarian New Zealand” died.

As we approach the 40th anniversary of Douglas’ blitzkrieg, it would be healthy for the country to adopt a more balanced position, one that acknowledges the failures of Muldoon’s protectionist economy but also points out that, in making New Zealand more open to the world, it was not necessary to make it more unequal. The country could have become more like Denmark – flexible, dynamic, but with widely shared growth and world-class public services – rather than becoming a poor imitation of the United States, with all the attendant inequalities and social problems. Our account of this period must also find a way to acknowledge the progress made since 1984 – especially in the recognition of women’s rights and te ao Māori – that has run alongside the damaging rises in poverty and social dysfunction.

For his part, Kelly acknowledges that Muldoon left the country in a mess – “there was a need to make change”, he notes – but does little to sketch out a compelling alternative to Rogernomics. This is not a criticism: in the post-1984 era hardly anyone has. Contra the fevered imaginings of the right-wing commentariat, this Labour Government has not – bar a couple of landmark pieces of legislation like the Zero Carbon Act – really upturned Rogernomics’ political settlement. Taxes remain low by European standards, unions weak, state housing neglected.

A different vision is waiting to be sketched out, one in which the economy serves people and planet – Kate Raworth’s famous 'Doughnut' metaphor comes to mind – and a sense of collective endeavour suffuses politics, public services and the country as a whole. Revitalised industrial policy, the indigenous independence foreshadowed in Matike Mai, and a fairer tax system would all play their parts in this new intellectual world.

Keeping the Party in Tune does not really enter this territory. It stresses instead a home-spun concern for basic kindness and decency that, even in this more individualistic age, is familiar to most New Zealanders. Kelly writes: “Any government worth its salt, if it ignores or pays insufficient attention to the poor in our society and allows the gap to grow between them and those at the top, or does nothing to reduce it … does not deserve the privilege given to them to govern.” It is perhaps this explicit defence of the underdog that gives the book its main character, and reminds us of what politics has lost.

Keeping the Party in Tune: How politics and music shaped my life by Graham Kelly (Graham Kelly Publishing, $35) is available in bookstores nationwide.