Victor Billot on a history of state surveillance in New Zealand - and the modern threat of China

Twenty or so years ago I visited the late Dick Scott at his Mount Eden home. I had recently got a job putting together the Maritime Union magazine, and had been inspired (and intimidated) by Scott’s accounts of the 1951 Waterfront Dispute. As a young man, he had much the same job as me – as the editor of the wharfie’s newspaper The Transport Worker.

Scott did the job throughout New Zealand’s most severe dispute which turned very nasty, very quickly. Emergency wartime regulations were used by the National Government of Sid Holland, chafing at the bit after long years in opposition to have a crack at the militant section of the New Zealand working class.

1951 saw heavy curtailments of freedom of speech, the closure or banning of public meetings, and other heavy-handed tactics such as the raiding of houses and violent repression of protests. Shortly after the end of the bitter struggle, where the wharfies and their allies were comprehensively crushed, Scott wrote a seminal and partisan history entitled 151 Days. He was an old man by the time I met him, hard of hearing but still sharp. He put up with my no doubt familiar questions. He had a well-known Tony Fomison painting on his kitchen wall that he had been gifted by the artist. He said he’d been offered a lot of money for it, but wasn’t interested. “I like it there,” he said. He seemed to warm-up a bit over our conversation and as I was leaving, he said, “Wait a minute, I have something for you.”

He went back into the house and returned with a small cyclostyled pamphlet. It was an original 1951 pamphlet he had helped produce. Producing information in favour of the locked out wharfies was illegal.

At the time, not many voices were raised in defence of the supposed open society we are proud of. A few academics and lawyers disapproved of the ‘emergency regulations’. The Labour Party prevaricated. Meanwhile the watersiders and a few other union allies were systematically pounded into submission, attacked in public, silenced, beaten by police, watched their families go hungry (it was also illegal to feed the families of locked out workers), and reviled in the media.

The gentlemanly pipe-smoking cartoonist of the New Zealand Herald, Minhinnick, did a series of cartoons representing these otherwise ordinary New Zealand workers as unshaven thugs, fifth columnists, and lazy malingerers. Many of the wharfies had served in the Second World War and were stunned to find themselves branded as traitors. More than one spoke about the lifelong bitterness they carried with them as a result of their treatment.

It was a shocking time, largely submerged in New Zealand history. It brought into sharp relief the ability of the State and its agents to go on the attack against those who challenged the status quo. It showed New Zealanders were prepared to snoop, hound and ruin lives, an attitude that did not gel well with the relaxed, decent self-image of ‘God’s Own Country’.

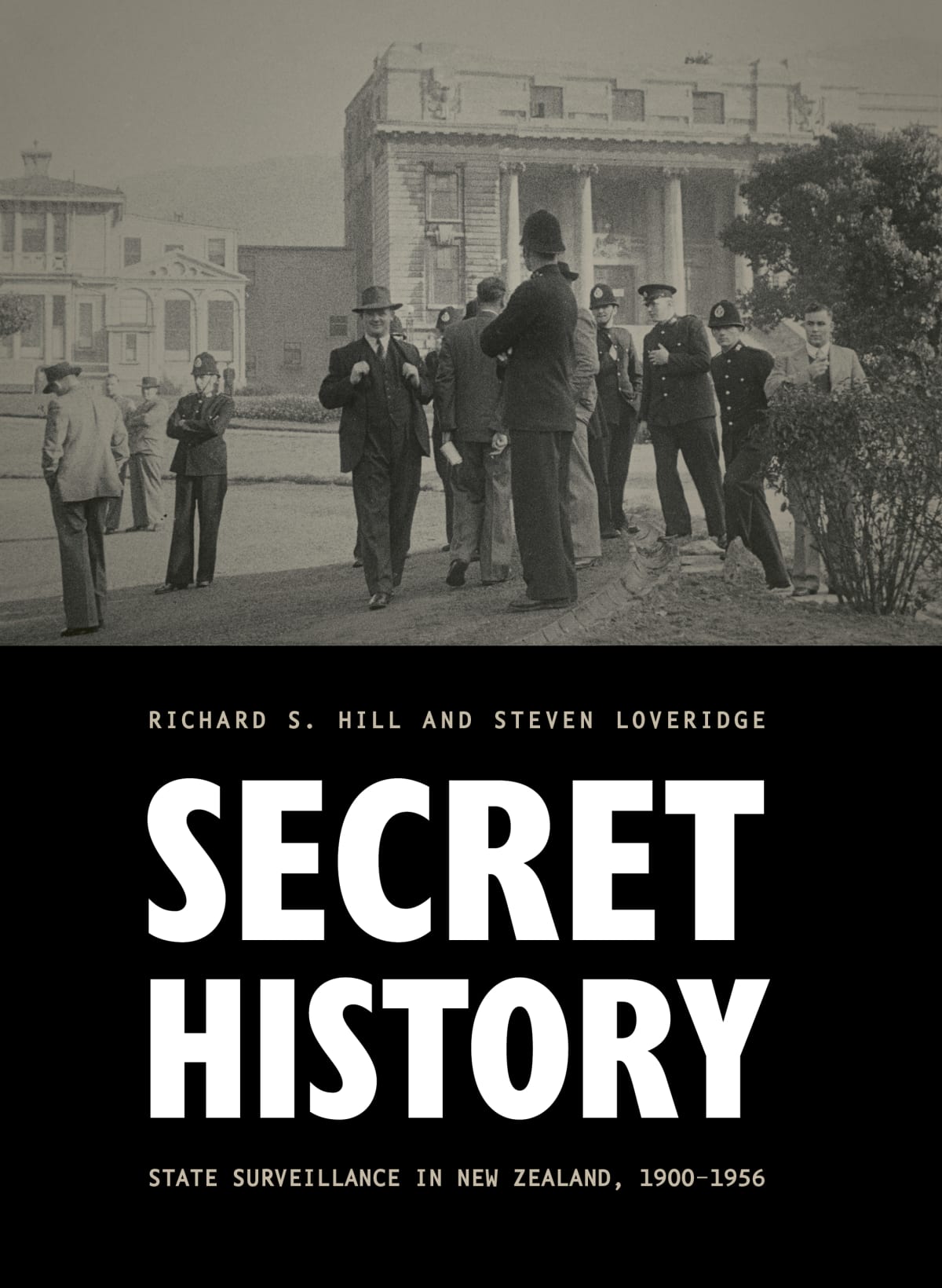

1951 features heavily in the new, massively detailed and co-authored study Secret History: State surveillance in New Zealand, 1900–1956, in the context of wider issues of the Cold War. After reading this book, I went and ferreted out the old leaflet Dick Scott had given me. Its meaning seemed even more heavy, a token of a time when it was unlawful to state an opinion, and when police searched the homes of New Zealanders not for illegal drugs or stolen goods, but for illegal books and leaflets.

Secret History is a substantial book, a rigorous academic study of political policing in New Zealand from the beginning of the 20th century to 1956. The history it contains is anything but dull. Even if New Zealand was a remote, small colonial outpost at the start of the twentieth century (with Māori pushed to the margins), at the fringes of mainstream society there were colourful characters and a fermenting of new and radical ideas.

Secret History illuminates a lost world – a world where public servants saw themselves as loyal Imperial minions, where the bulk of communication was carried out through letters and printed material, where there was one radio station whose content was overseen by the State.

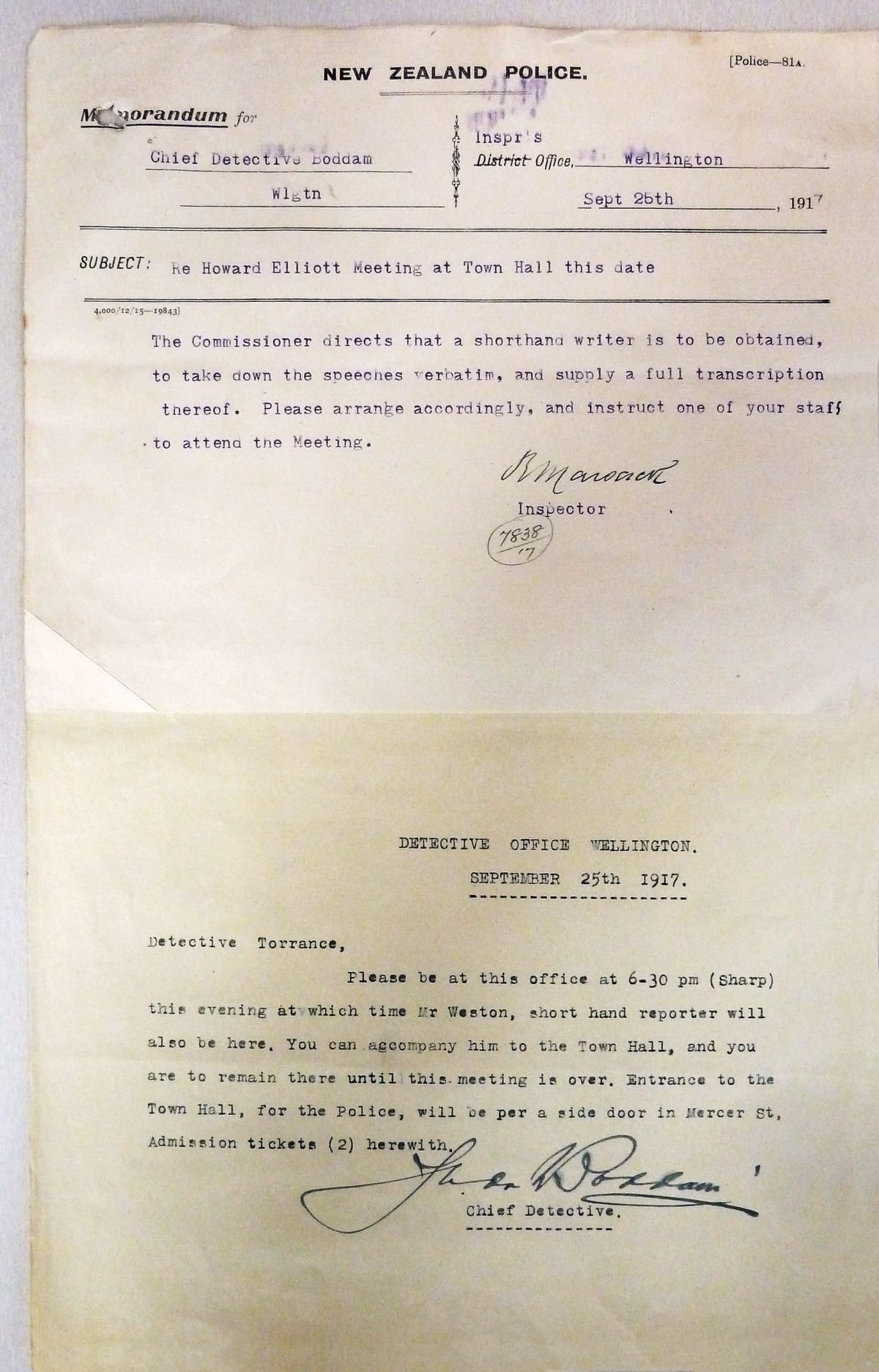

There is extensive analysis of the finer points of interdepartmental intrigue in the Police and bureaucratic machinations, the petty resentments between plainclothes detectives and uniformed officers. An early attempt to set up a police union was rapidly squashed (it eventually was permitted.) There were tensions between the Police with their ‘professional’ attitude and defence officials about whose job it was to keep oversight of subversives, especially ‘foreigners’ and ‘Bolsheviks’ suspected of being under the direction of alien powers during times of war.

‘Mission creep’ happened a century ago. Officials tended to see subversion festering throughout the Dominion, which in turn justified greater status and investment in their surveillance activities. This ‘reds under the bed’ mentality was also promoted in the establishment media whose line was largely mindlessly subservient, crawler mode middle-class prejudice. (Some things have not changed that much.) The different leadership styles of the senior leadership strata of career policemen also influenced outcomes.

The police charged with maintaining order took a broad view of their responsibilities. Their own ideology was of course taken for granted. The political outlook they brought to the job was in general conservative, imperialist, and reactionary, even by standards of the day. Anyone who disagreed with the system was automatically under suspicion.

There is great detail here about the interaction between senior police and their political masters, and the personal ambitions of these figures. In fact, the level of detail becomes overwhelming for a casual reader. It is of course necessary given the definitive nature of the research. That’s the type of book it is.

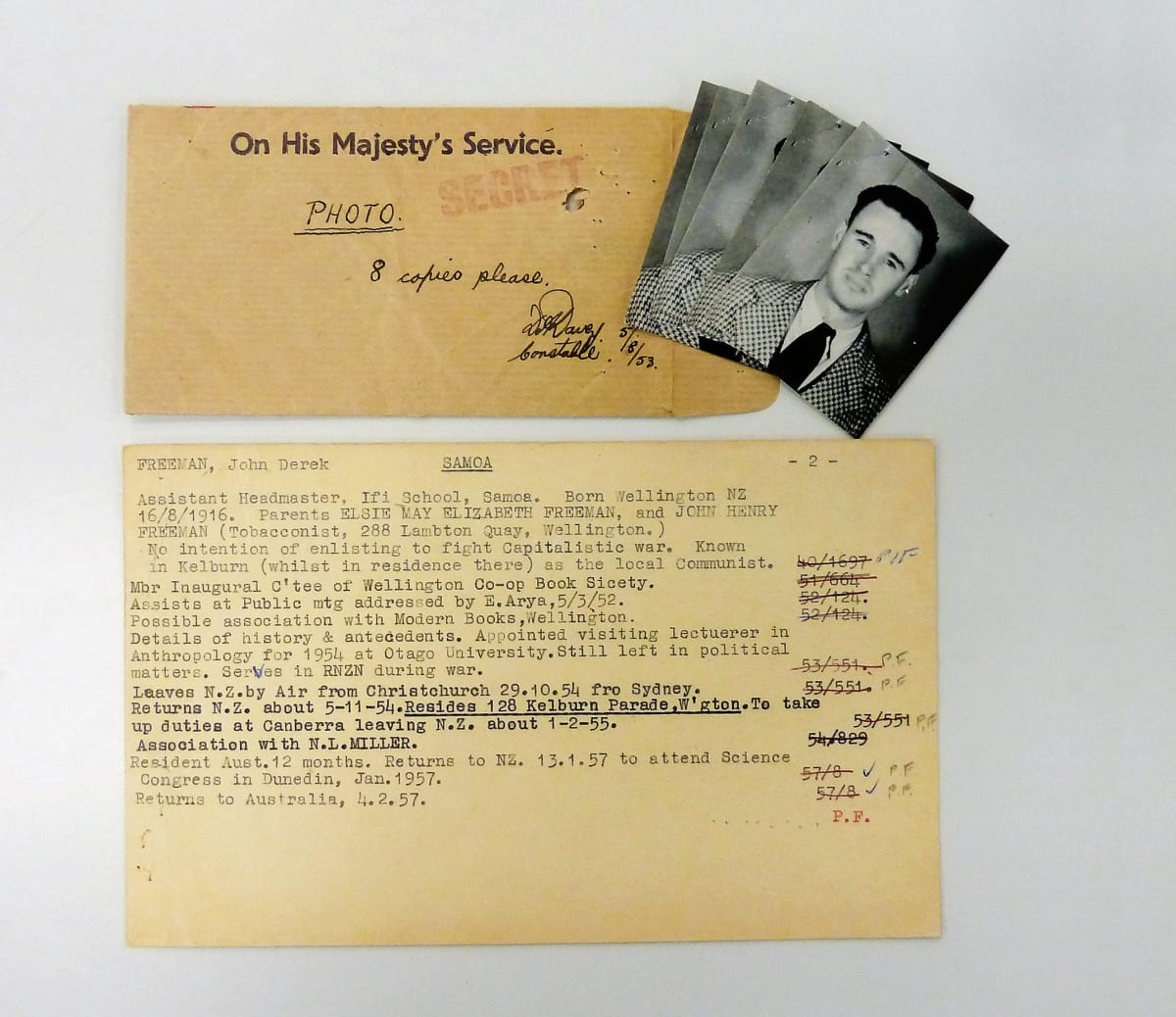

But at the same time, this is also is a kind of default history of the political and sometimes personal lives of those under surveillance. It covers both the watchers and the watched.

*

One thing I took from Secret History is the first half of the 20th Century was dominated by the police and the political establishment fighting an ongoing war against the political left, with a particular focus on the small Communist Party, which did indeed engage in increasingly optimistic and then delusional support of the Soviet Union as it degenerated under Stalin.

Some of it seems faintly bizarre looking back from our era where socialist politics of this type have vanished from New Zealand, to be replaced by conspiracists and wokesters battling it out against a background of capitalist realism.

The years leading up to the First World War were marked by increasing agitation. There was widespread concern amongst the well-to-do classes and political establishment about the growth of militancy, encapsulated by the “Red Feds,” the newly formed radical union federation. The reforming Liberals had been replaced by a conservative Reform Government led by Prime Minister William Massey. Things came to a head with the 1913 General Strike where ‘Massey’s Cossacks’ – mounted “special” constables (usually farmers armed with cudgels) – were unleashed on groups of striking workers.

Surveillance was enforced by people with strong ideological preferences of their own, who saw themselves as guardians of all that was good and right

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 had a contradictory effect. In some ways it collapsed the support for radical social change as the mood shifted towards patriotism. However, there was a small but active minority who opposed the war, or in some way criticised the State, and they came under the purview of an emboldened and enabled police who saw a diverse range of malcontents and misfits to keep under control. We think globalisation is a modern thing but the world 110 years ago was highly globalised. People were coming and going constantly. New forms of communication and technology were speeding life up. There was a ferment of ideas as literacy grew and the working-class grew increasingly confident about their rights.

The First World War saw the growth of the security state. Communists and socialists were high on the watch list, especially after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Then there were other radicals such as the “Wobblies”, members of the anarcho-syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World, whose roving advocates travelled around the Pacific.

Christian pacifists refused to go to war (one was Archibald Baxter of Otago, who wrote a disturbing account of his torture by the military). There were many New Zealanders of German heritage or citizenship who were instantly under suspicion (other Europeans also suffered the same fate) and vulnerable to harassment, false accusations and public scorn. This extended to those of Irish Catholic background, who fell under deeper suspicion after the bloody repression of the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916. They too came under the eye of the censor and the secret police.

And particular iwi or groups of Māori were identified as problematic. The prophet Rua Kenana and his people refused conscription. Their village in the remote Ureweras was raided by police in 1916, shots were exchanged, and two died – one of them the son of the prophet. Kenana was sentenced to hard labour for resisting arrest.

*

The purpose of policing was to protect the State and society, but defining this in law and in practice was not a rigorous process. In reality it was left to be enforced by people with strong ideological preferences of their own, who saw themselves as guardians of all that was good and right. God, King and Country, plus capitalism and hierarchical social relations, in other words.

The contradictions became obvious in 1935 when a Labour Government was elected in the midst of the Great Depression. Now senior police were dealing with Ministers who had previously been arrested and jailed for their political activities. Peter Fraser, who served as Labour Prime Minister for almost all of the 1940s, had spent a year in jail during the First World War for speaking out against conscription.

Another example of a monitored subversive who rose to become part of the establishment is noted in Chapter Four. In 1921, police sought information from their American counterparts against a young radical by the name of Fintan Patrick Walsh, described as a “dangerous man of excitable temperament.”

Walsh would rise to the leadership of the Seaman’s Union, and eventually become President of the national union body the Federation of Labour, an office he held to his death in 1963. This was in the days when this position meant something. Later in his career he became noted for his authoritarian methods as he dominated the large Union movement, ruthlessly squeezed out left wing challengers, and operated fairly much as a law unto himself, as one of New Zealand’s most powerful figures at a time when wages and conditions were centrally negotiated by employers, Unions and the State. Walsh’s nickname was ‘The Black Prince’ which apparently referred to both his saturnine looks and tactics.

While the security forces had to deal with this confusing development, it helped that the rise of the radicals saw many shed their radical baggage. Fraser was happy for the communists to be kept under watch. One of his last acts as Prime Minister in 1949 was to hold a successful referendum to continue with compulsory military training, against the opposition of the left. Likewise, the ‘Black Prince’ was instrumental in working against militant unions in the 1951 waterfront dispute. Poachers had turned gamekeepers.

Then of course there are the oddities and sometimes ludicrous situations caused by the sometimes amateurish Kiwi efforts of the police and related State officials. There is an element of humour in some, although of a dark kind. In the 1930s, the inventor of a supposed ‘death ray’ was taken into an official protection programme and relocated him to a secret laboratory on Somes Island in Wellington Harbour. The death ray was later dismissed as worthless.

Later, during the Second World War, a new Security Intelligence Bureau was set up under the directorship of a Major Folkes (described as "pale, thin, weakly looking, with semi-thick spectacles …"). His career ended ignominiously after his pursuit of a non-existent spy ring based out of Rotorua ended in fiasco. He had been duped by a couple of ex-cons turned informants, one of whom managed to get himself put up at Rotorua’s best hotel at the taxpayer’s expense during surveillance operations.

Detective Sergeant Nuttall of Dunedin advanced innovative styles of information gathering. On his instructions a hole was drilled through a wall at the Good Templar’s Hall and disguised by a picture, so officers could listen in on the proceedings of the local Militant Workers League.

Great effort was expended on monitoring, interfering, and harassing. The victims were often New Zealanders who were simply those of “independent mind,” as the old poem by Robbie Burns celebrates. All this effort seemed to achieve little in the way of "protecting" New Zealanders.

This musing about the distant past might seem to have little relevance to the modern world. But the culture and focus of the modern security apparatus has its roots in this world. Jumping forward a century, the most serious terrorist attack in New Zealand’s history did not come from a bomb-throwing anarchist, a rebel Irishman or a Māori insurgent, as the secret police of the past obsessed about. In fact, many of the causes championed by these ‘threats’ have now come to pass – and society is better for it.

The terrorist act did come though, in 2019. It came from a right-wing extremist convinced white, Christian civilisation was being overrun. His answer was to murder defenceless men, women and children in cold blood. The question has been asked as to why our modern intelligence and security agencies did not detect this agent of carnage who plotted in our midst. This history perhaps gives us some starting points to consider, in the roots and culture and most obvious blind spots of the State’s guardians of ‘our way of life.’

*

Through the accumulation of massive detail in Secret History, from the sifting through the minutiae of official records, a complex picture of the Police (and subversives) emerges. Outside in the everyday world, society evolved despite the best efforts to control and freeze change. What the secret policemen of 1923 would have made of life now would be interesting to consider. I suppose we still live in a hierarchical, capitalist society, although unrecognisable in most other ways.

A recurring thought I had reading this book was how radically New Zealand had changed in the decades since the era it covers. However, this is not the distant past. Many of the events recorded here are within living memory. Obviously, there has been a shift towards greater sensitivity around ‘human rights’. But as the Urewera raids of 2007 demonstrated, the fault lines of history go deep.

We live in a time when the flow of information is so great it is effectively uncontrollable, and the focus has shifted more to the manipulation and degradation of information, so the methodology of the security State has evolved.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, and the evolution of the People’s Republic of China to a form of authoritarian State capitalism, has blown up the main 20th century theme of secret policing in New Zealand, or at least reoriented it so dizzily that it is hard to grasp. The ideological challenge has vanished – after all, we are all capitalists now. Concerns about China are about power politics and the shuffling of national interests, not international working-class revolution. The pictures of Karl Marx up on the wall at a meeting of the Chinese Communist Party have all the authentic quality of a Mickey Mouse costume in Disneyland.

Nonetheless, China is now New Zealand’s major trading partner. Our exports to China are far greater than those to the US, UK, Australia and Canada combined. Yet the Anglo-American nations remain our military and security partners. We are enmeshed in the AUKUS alliance, creating an uncomfortably ambiguous position. (Our relationship to the big players of the Anglo-American fraternity has echoes of the hapless Madge, Dame Edna Everage’s silent bridemaid – an “oppressed, inarticulate New Zealand spinster who life had passed by.”)

The new head of the SIS, Andrew Hampton, has an astoundingly good record collection

National and Labour Governments have eagerly jumped into free trade deals that further integrate our economic life with China. Mass immigration from China has been encouraged. At the same time, China is seen as a threat to New Zealand’s democracy. Given New Zealand’s historic racism towards Asians, and the stress on housing and infrastructure in recent times, it’s surprising there hasn’t been more open ethnic conflict.

Recently, the new head of the SIS, Andrew Hampton, released a report that noted a small number of states engage in interference against New Zealand, and “some do so persistently and with the potential for significant harm.” The names pointed to were the People's Republic of China (PRC), the Islamic Republic of Iran and Russia.

Here I should make a disclosure that I know Andrew Hampton, although I haven’t been in contact for a number of years. My purpose mentioning this here is to illustrate in a roundabout way the contemporary security scene, in comparison to the world outlined in Secret History.

Andrew and I used to play in small time rock bands back in the early 1990s. I was in Dunedin and he was in Christchurch, and me and my band mates used to crash at his flat in Riccarton Road after we headed up to the Flat City to play at Warners or the Dux or some other joint. We were both Politics students as well. Even at this stage, it was obvious that Andrew was meant for bigger things, and within a few short years he had disappeared (or appeared) on an impressive career trajectory into the upper reaches of the bureaucracy in Wellington. His later appointment as head of the Government Communications Security Bureau (prior to the SIS) was for me a little surreal but it also made complete sense. After all, the security agencies were obviously being upgraded to a new 21st century image and the appointment of a mainstream public servant as their head signalled this modernising shift clearly.

After his GCSB appointment, Andrew made a notable guest appearance on a music show on Radio New Zealand where he discussed his love of indie guitar rock (and it is true he had an astoundingly good record collection).

*

I guess my point here is – apart from an example of the small town, one degree of separation aspect of New Zealand society – is how the contemporary era is so much more contradictory and complex, and how deeply the world has changed. In the 1950s. where the idea of a vinyl fiend and ‘civilian’ public servant being in charge of the lead security agency would have been far-fetched to say the least.

The recent imbroglio about foreign spies in New Zealand brought about by his release of the report is a case study of how strange things have become. Our security agency is openly stating we have agents of foreign powers operating in New Zealand in fairly hostile ways, yet at the same time we are deepening our relationship to those powers (modern day Russia is the current exception.)

Politically this leads to all sorts of absurdities as the wider population struggle and often fail to comprehend the processes at work. Actually, I struggle with them too.

Consider that at the same time as we engage with China, we have a radicalized right wing who abused Jacinda Ardern as a “communist.” Remember the placards at the Parliamentary protest, or the signs on tractors at Groundswell meet ups? The same people write in Facebook comments we need to get rid of the “communist” Government, then confusingly also attack it as promoting apartheid through co-governance.

Despite this reasonably widespread perception, the left are nowadays bigger critics of the “Communists” than the mainstream Right. In 2010, then Green Party leader and MP Russel Norman was manhandled by Chinese security agents on the steps of Parliament when he staged a protest against visiting Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping. Norman had been waving a Tibetan flag that was ripped from his hands. He was roundly condemned at the time by the National and ACT leadership. The-then Prime Minister John Key was highly embarrassed by the fracas and apologised to the Chinese, and since that time has gone on to become a great booster of China.

In 2022, Key’s positive comments appeared in Chinese state media: “I think the very strong focus of the Communist Party of China has been about lifting people out of poverty, about economic growth and development. The CPC focused on how to improve the financial well-being and therefore opportunities of the least well-off in China.” The concept of a former National Party Prime Minister (and merchant banker) praising the results of Chinese Communists in helping the lot of the downtrodden proletariat is surreal too. Sixty or 70 years ago we were preparing for an Asiatic horde to sweep down and install Maoism in Johnsonville and Geraldine. Our soldiers died – and killed – in Korea and Vietnam. The bitter irony of the evolution of the National Party and the mainstream New Zealand political right – the natural ‘party of Government’ and the political establishment – from bomb droppers and paranoiac red-baiters to PR agents for Red China seems to be lost.

Key’s comments reflect the attitudes of smart money, the people who know what is going on. One could see him as operating quite successfully in the Chinese system – Comrade Key, a loyal party member developing the People’s Capital Markets, in a very, very long and drawn-out transition period towards the classless society.

Meanwhile, the dimwits thundering along in their tractors screeching about the “Communists” are trapped like hapless bugs in the ideological amber of the Jurassic Age. The livelihoods, fate and indeed new tractors of the rural and provincial communities of New Zealand are now inextricably linked to “Communism” – or at least, the shape shifting, flexible ideology that has taken its place in ascendant China, our Great Frenemy.

In all this, it is worth remembering the only incident of state terrorism in New Zealand by a foreign power was by one of our allies, France, in the 1985 bombing of the Rainbow Warrior. A parallel to how domestic terrorism in New Zealand has been the territory of the extreme right, including the Trades Hall bombing of 1984, despite the State’s constant obsession with the radical left.

No doubt these issues will form part of the planned, post-1956 follow up to Secret History.

This monumental scale and density of this volume will be regarded as a central reference work in New Zealand history. There are several sets of high-quality colour plates throughout the book featuring some well-selected illustrations. Pages 287-410 are made up of exhaustive footnotes, comprehensive bibliography and index – only fitting for a book about the keeping of detailed records.

Secret History: State surveillance in New Zealand, 1900–1956 by Richard S Hill and Steven Loveridge (Auckland University Press, $79.99) is available in bookstores nationwide.