Maksim Goldenshteyn recounts a story his late grandmother once told him about how, as a 4-year-old child, she snuck out of a Jewish ghetto during World War II to retrieve her favorite dolls that had been left behind the day her family was forcibly evicted from their home in occupied Soviet Ukraine.

“She knew even at that age that because she had lighter hair and blue eyes, she could pass for a local Ukrainian girl,” said Goldenshteyn. “She put on a kerchief and slipped out of the ghetto.”

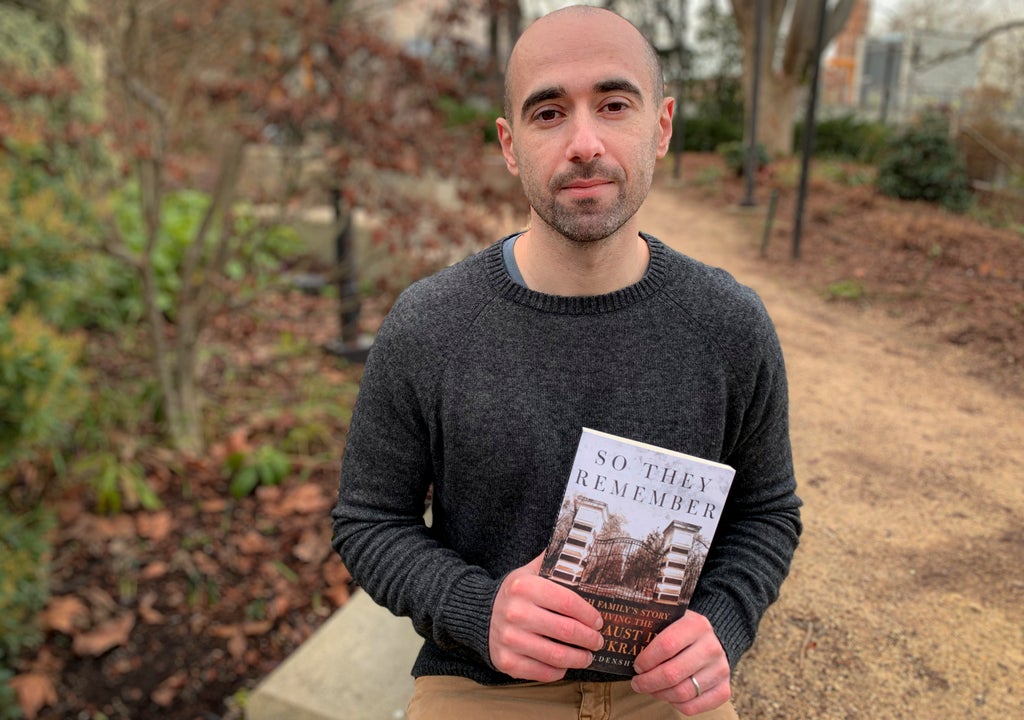

It is one of the stories that Seattle native Goldenshteyn tells in his book, “ So They Remember,” which recounts — with a blend of intimate family memoir and vigorous historical research — the Holocaust in Transnistria a territory in occupied southern Ukraine that was controlled by Romania, a close ally to Nazi Germany for most of the war.

In that territory, where around 150 camps and ghettos operated, there played out a lesser-known but equally sinister chapter of the Holocaust, where hundreds of thousands of Jews were brutalized, exploited, and murdered.

Many died of starvation; some succumbed to disease or exposure; some were executed.

Goldenshteyn, 33, whose family moved to the U.S. as refugees from the former Soviet Union in 1992, says he heard fragments of his family’s past while growing up, but he never linked it to one of humanity’s darkest chapters.

“They didn’t really align with the image of the Holocaust that I thought was representative,” he said. Then, 10 years ago, his mother told him the story. “I was shocked at first,” he said.

Moved by what he’d learned, Goldenshteyn embarked on a decade-long journey researching a part of the Holocaust he feels is largely overlooked.

His starting point was to interview his grandfather, Motl Braverman, in his Seattle home over a series of weekends. Braverman, who died in 2015, languished as an adolescent with his family in the remote Pechera death camp, which became known to many prisoners as the “death noose.”

He cuts a central figure in the book. “My grandfather spoke with a certain detachment, as if relating someone else’s experiences,” Goldenshteyn writes. “Later, he assured me that the death camp he survived was never far from his mind.”

Awareness of Romania’s role in the Holocaust, at home and abroad, is far less than that of the Nazis' role. But in Romanian-controlled territories under the military dictatorship of Ion Antonescu, between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews, plus some 12,000 Roma, were killed during the war. The decades of communism that followed, much like in the Soviet Union, all but erased memories of the Holocaust.

“I don’t think many people realize that Romania was Germany’s principal ally in the East,” Goldenshteyn said, adding that the country’s communist period under Nicolae Ceausescu became the “traumatic history that is more immediate” to Romanians.

A late 2021 study by the National Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania “Elie Wiesel,” showed that 40% of respondents were not interested in the Holocaust. Nearly two-thirds of the 32% who agreed that the Holocaust took place in Romania mistakenly identified the deportation of Jews to “camps controlled by Nazi Germany.”

Stefan Cristian Ionescu, a historian and Holocaust expert at Northwestern University, said that most Romanians “think that it’s a responsibility of Nazi Germany.”

“I think a lot of Romanians still have a problem accepting that the Antonescu regime and the Romanian authorities … were involved in the Holocaust,” he said. “In the mass murder, deportation, and dispossession of Jews in Romania, and in occupied territories such as Transnistria.”

In a push for wider public awareness, Romanian lawmakers passed a bill last fall to add Holocaust education to the national school curriculum, a move that was applauded by many. But it was met with controversy in January when the far-right Alliance for Romanian Unity, which holds seats in parliament, called it a “minor topic” and an “ideological experiment.”

David Saranga, Israel’s ambassador to Romania, strongly condemned the party’s comments online and said such statements are “outright proof of either a lack of taking responsibility, or of ignorance.”

Goldenshteyn believes that Romanian authorities have made progress in recent years in acknowledging the country’s role in the Holocaust, and said he was troubled by the party's comments but also encouraged by the reaction of the diplomatic community.

“It’s important for any country with a dark past to confront it,” said Goldenshteyn, the father of two small children. “Because it’s impossible to chart the way forward without knowing where you’ve been. There is not enough knowledge about what happened during the Holocaust in Eastern Europe.”

In late January at a Holocaust memorial event at the Choral Temple Synagogue in Romania's capital, Bucharest President Klaus Iohannis said that the pandemic has “amplified the virulence of antisemitic attacks” and warned against “conspiracy theories and misinformation.”

“Let us not close our eyes to these real dangers, which are often cleverly hidden behind a claimed freedom of expression,” Iohannis said.

At the Pechera camp, the gates of which sported a wooden sign that read “Death Camp,” hunger was such that cases of cannibalism were reported. As an adolescent, Motl Braverman would evade guards and take perilously long roads in sub-zero temperatures to return with small amounts of food to keep his family alive. He would later help others escape from the camp to head to relatively safer ghettos.

Goldenshteyn said that what affected his grandfather most was that “his story was never validated” because of the taboo about discussing the Holocaust. “So They Remember” tells that story, and it is as much about human bravery and kindness as it is about the depraved indifference to human suffering.

“I think the strength of this book is that it combines this personal, family story ... with historical research. It makes it interesting for the general public, not just for a small circle of scholars,” Ionescu said. “There is still a lot to be uncovered about Romania’s participation in the Holocaust — specifically this territory of Transnistria.”

Goldenshteyn writes in his book’s prologue that, after his grandfather died, he avoided listening to the audio recordings of their interviews made five years earlier. Then, in 2017, when he did finally press play, he heard his late grandfather's words.

“You should write this so that no one forgets,” his grandfather said. “So they remember.”