Soon, bones said to belong to Mark, who died in or around 68 A.D., will be on display at the Shrine of All Saints in Morton Grove.

The shrine is home to thousands of religious relics — objects “often associated with a saint’s body” or belongings that are kept for “historical interest or spiritual devotion.”

The Rev. Dennis O’Neill, who founded the shrine, says he recently purchased ulna (arm) and carpal (hand) bones from a middleman who got them from the family of a deceased Italian cardinal who’d gotten them from a Venetian church where most of Mark’s body might be interred.

“It’s unquestionably St. Mark, as sure as anyone can be,” O’Neill says of the bones. “He’s someone who knew Jesus, he wrote the first of the four gospels and was present at all the important events — he was right there at the beginning.”

While Mark wasn’t one of Jesus’ 12 apostles, he was believed to be close with Peter, a prominent disciple some scholars believe is likely to have been one of the main sources for the Gospel of Mark.

The gospels of Matthew and Luke each appear to draw from Mark’s book, which is the “oldest and shortest” of all four and “emphasizes Jesus’s rejection by humanity while being God’s triumphant envoy,” according to a description by Franciscan Media. “Probably written for Gentile converts in Rome — after the death of Peter and Paul sometime between A.D. 60 and 70 — Mark’s gospel is the gradual manifestation of a ‘scandal’: a crucified messiah.

“We cannot be certain whether he knew Jesus personally. Some scholars feel that the evangelist is speaking of himself when describing the arrest of Jesus in Gethsemane” that preceded his crucifixion, according to the Franciscans.

The account in the Gospel of Mark says, “Now a young man followed him wearing nothing but a linen cloth about his body. They seized him, but he left the cloth behind and ran off naked.”

Other scholars question whether Mark was actually the author of the book bearing his name.

Mark’s home in Jerusalem also is thought by some religious scholars to have been a meeting point for Jesus and the apostles — possibly the site of the Last Supper and later where the Holy Spirit was said to descend on disciples after Jesus’ crucifixion, resurrection and ascension to heaven.

Afterward, as the disciples spread Jesus’ teachings, Mark traveled with Paul and Barnabas on an early missionary trip to what is now Turkey, according to traditional Christian accounts.

Paul’s significance to Christianity is vast. In part, that’s because he “translated both facts and doctrine into a broad theological synthesis characterized by a universalism of salvation, an intricate theory of grace and a central function of Jesus as man and as God,” according to Encyclopedia.com — an apt description, experts say.

Mark was believed to have been the first bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, where there are conflicting stories of how he died — peacefully or violently, dragged through the streets with a rope around his neck.

In 828 or so, merchants smuggled Mark’s body out of Alexandria by hiding it in “wicker baskets . . . protected by cabbage leaves and pork,” according to the Basilica di San Marco, the ancient Venetian church that says it houses most of his remains today.

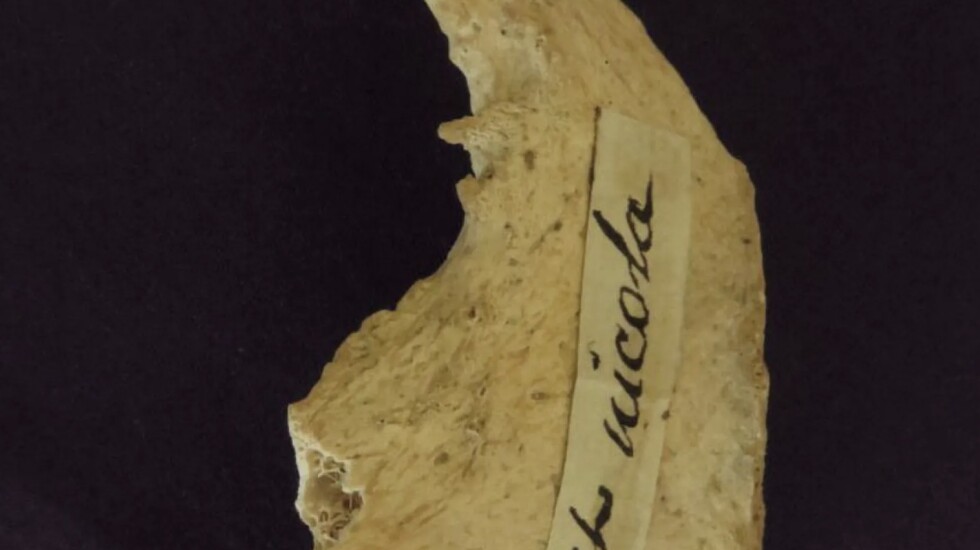

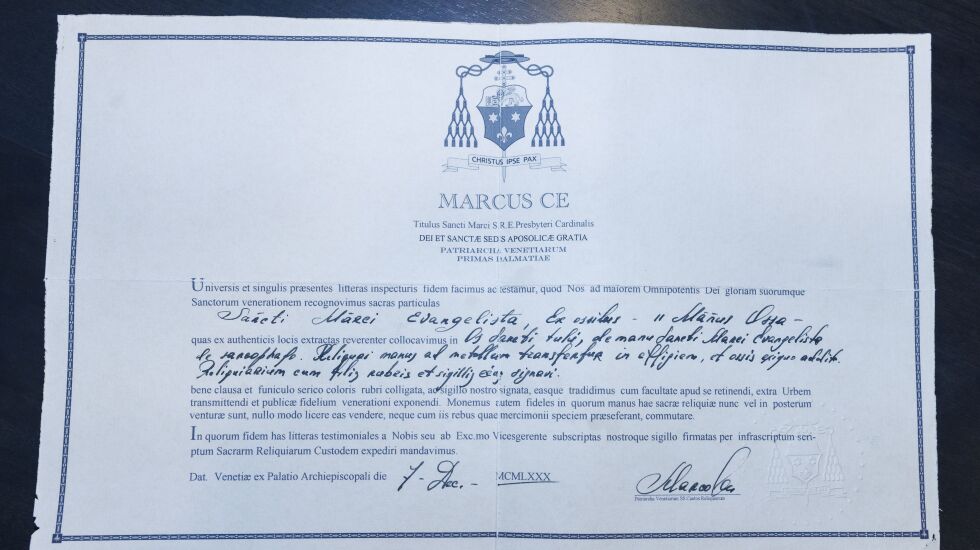

In 1980, the patriarch of Venice, the late Cardinal Marco Ce, “removed from the sarcophagus the right ulna and a carpal bone from the right hand of St. Mark and placed them in a gilded bronze arm reliquary,” according to a written account O’Neill recently authored for parishioners.

“He kept this reliquary in his private collection,” and, after his death in 2014, “his family obtained it,” according to O’Neill.

He says a dealer bought the bones, which, along with other relics, were being kept in Italy “in a barn wrapped up in old vestments,” and the priest bought them from him.

He declined to discuss the cost but says he uses his own money to obtain relics, “rescuing them back for the church.”

The shrine, located in what used to be a multipurpose room at the now-closed St. Martha School, includes relics associated with more than 3,000 saints, either given to or purchased by O’Neill, sometimes over eBay.

Many of the relics were from shuttered Catholic churches whose altars often contain what are said to be remnants of saints, churches that had seen attendance plummet amid growing secularization in the West.

O’Neill says relics serve a number of functions, including helping the faithful better understand and model holy women and men of the past and providing another means of reflection and connection with God.

Georges Kazan, an archaeologist who studies Christian relics, wrote in 2015: “Many Christians saw relics as earthly repositories of God’s Holy Spirit, able to work miracles and bestow healing. They became invaluable commodities and symbols of status, particularly during the Middle Ages. After the Reformation, the trade in relics was seen as the embodiment of the worst excesses of superstition and cynicism.”

Several years ago, Kazan and a colleague took tiny samples from items at All Saints, including a chunk of pelvis thought to possibly be from St. Nicholas, a Greek bishop — now familiarly known as Santa Claus — from the third and fourth centuries in an area known as Myra, now part of Turkey.

The result of subsequent radiocarbon testing “suggests that the bone dates to the time of the saint’s death in ca. 343,” Kazan wrote. “This means that, while it is not possible to identify its precise origin, science cannot disprove the tradition that this is a relic of St. Nicholas. For the faithful, this relic therefore bears witness to the life of the saint who is today celebrated by many as Santa Claus.”

O’Neill knows that some of his relics might not be authentic, that they might have been misidentified over the years or forged.

Still, he says, if they bring people closer to God, they have value.

O’Neill says he’d be fine with someone similarly testing the bones attributed to Mark to see whether they could be proven to fit someone who lived during his time and offer further evidence of their authenticity.

But he says that, given what’s already known, “I don’t see the need.”

O’Neill is a Catholic priest, and the shrine is at a Catholic parish. But he says, “All Christians are interested in the four gospel writers . . . This is everybody’s gospel.”

Over the years, relics also have played a role in other religious faiths, including Eastern Orthodox and some Protestant traditions as well as non-Christian faiths.

Mark’s relics, which were shipped to O’Neill in February, can be viewed by the public at All Saints, 8523 Georgiana Ave., Morton Grove, mostly by appointment, starting in a week or so.