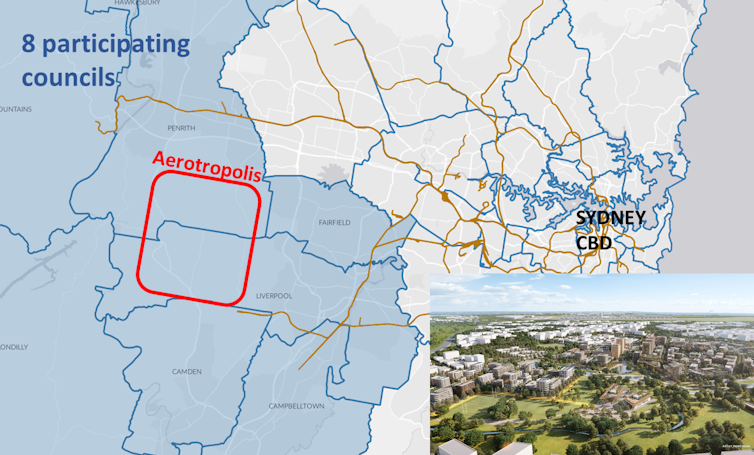

A massive project is unfolding in Sydney’s Western Parkland region. The building of a new city from the ground up is central to an infrastructure-led restructuring of metropolitan Sydney. The catalysts are the Western Sydney City Deal and the Western Sydney Airport being built alongside the new Bradfield City.

Bradfield city is being developed on unceded Aboriginal land with complex ongoing settler-colonial legacies and high stakes for diverse First Nations communities – including the largest urban Indigenous population in Australia. Yet it is named after a colonial figure with no connection to the land.

Our case study research acknowledges what is happening in the Western Parkland development as being at the forefront of urban and infrastructure governance across Australia. It’s particularly notable how all three tiers of government – federal, state and local – have come together in this massive project.

Yet we have also identified a range of concerns, including public consultation, project funding, urban heat and water demand, the need for affordable and public housing, and other social equity issues.

Read more: 3 planning strategies for Western Sydney jobs, but do they add up?

City’s name is not a good start

The case study is part of a three-year (2020-2023) research project, the Infrastructure Governance Incubator, across three universities – Sydney, Melbourne and Monash. Our study includes 55 interviews with key stakeholders from all tiers of government, as well as non-government and community voices.

Participants from across the board have seen the “Bradfield” naming as a shameful decision. It’s in stark contrast to the positive steps towards supporting Indigenous voices throughout the project. These steps include the award-winning Recognise Country guidelines, Indigenous-led design projects, a Koori Perspectives Circle, and new Indigenous roles within government authorities to support engagement efforts.

In Australian cities, it is critical we explore the role of infrastructure in perpetuating settler-coloniality and in making space for Indigenous-led futures. The complex challenges of a case like this can inform important discussions about how we might improve infrastructure planning to produce just and sustainable approaches.

Our research participants saw a need for governments to give meaningful attention to building relationships and developing cross-cultural understandings. This involves early conversations with Aboriginal groups and adequate resourcing for engagement. Too often, these groups are brought on late in processes after key decisions are already made.

Interviewees stressed the importance of governments “learning to listen”. This requires having the openness to hear what is being said even if inconvenient. Many participants wanted to see Indigenous voices empowered in decision-making, not simply advisory.

“Listening” also means “listening to Country”. Part of demonstrating commitment to relationship building involves sustainably protecting Country. Early and ongoing public scrutiny is essential to ensure the project’s short-term approaches align with long-term perspectives on sustainable outcomes. It may also mean taking steps more slowly and carefully to get it right.

The state government could take some key actions. These include committing resources to advancing the many Indigenous land claims and applying exemptions to development barriers such as biodiversity offset obligations. These currently treat First Nation stakeholders like a developer, ignoring their long and ongoing care for Country.

Many participants also raised serious environmental concerns, including water management and extreme heat in the new city. Heatwaves can be 5-10℃ hotter there than the rest of Sydney.

Some fundamentally questioned a massive greenfield development in such a vulnerable environment. Others saw this as a chance to make much-needed transformational changes to our planning systems.

Read more: Why Western Sydney is feeling the heat from climate change more than the rest of the city

Focus on jobs overshadows other issues

The political focus is on creating jobs in Western Sydney. Participants generally agreed it’s important to rebalance the metropolitan job market and economy.

However, many were concerned this focus has come at the expense of attention to other aspects of inequity, including access to affordable and public housing, public health and social services.

In terms of metropolitan planning, the centralised way the new strategy was adopted is a problem. The concept came from the then Greater Sydney Commission and was supported by the region’s councils.

The communities of the wider Sydney region, however, were not given strategic alternatives to consider. In particular, the concept was not put to traditional Indigenous custodians before being adopted.

One of the alternatives might have acknowledged the outer west as the hottest part of Sydney. It could instead have considered development in cooler parts such as Dural or the Central Coast. These sites might have been better placed to manage global warming challenges.

Read more: Half of Western Sydney foodbowl land may have been lost to development in just 10 years

Governance is still a work in progress

Our participants agreed the complexity of urban challenges requires a concerted effort to better integrate infrastructure decision-making. Part of the challenge is to overcome legacies of fragmented urban governance. It’s a result of divisions of responsibilities between tiers of government and siloed decision-making across and within these tiers.

The Western Sydney City Deal is generally seen as a major step towards better integration of all levels of government. Nevertheless, participants note important shortfalls.

City Deal funding committed to date is likely too little, given the major place-making ambitions. While it’s useful for short-term projects, local governments need solutions for their major long-term funding issues, especially in the face of new growth pressures. Lack of funding fuels existing cultures of competition between authorities.

The Western Sydney City Deal has had some welcome successes in improving collaboration between the three levels of government. Local governments have secured “seats at the table”, where they have been able to renegotiate the terms of collaboration and governance.

However, important questions remain about how governments collaborate with community infrastructure sectors, non-government organisations and community advocates. Many have raised concerns about lack of meaningful inclusion or being engaged too late for meaningful impact.

Read more: As Western Sydney residents grapple with climate change, they want political action

An example of these issues is the three-year review required under the Western Sydney City Deal signed in 2018. An independent university group completed the review in 2021. It has never been released to the public.

Interviewees told us the review was productive and made useful governance recommendations. However, some suggested it was not released due to state government discomfort with the findings.

We strongly urge the newly elected state government to make the review public and commit to a timely release of all similar documents in future. This will help build trust with the community.

Tooran Alizadeh receives funding from Henry Halloran Research Trust and Australian Research Council. The Infrastructure Governance Incubator is funded by the trust and partnered by the Planning Institute of Australia.

Glen Searle receives funding from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Rebecca Clements receives funding from the Henry Halloran Research Trust.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.