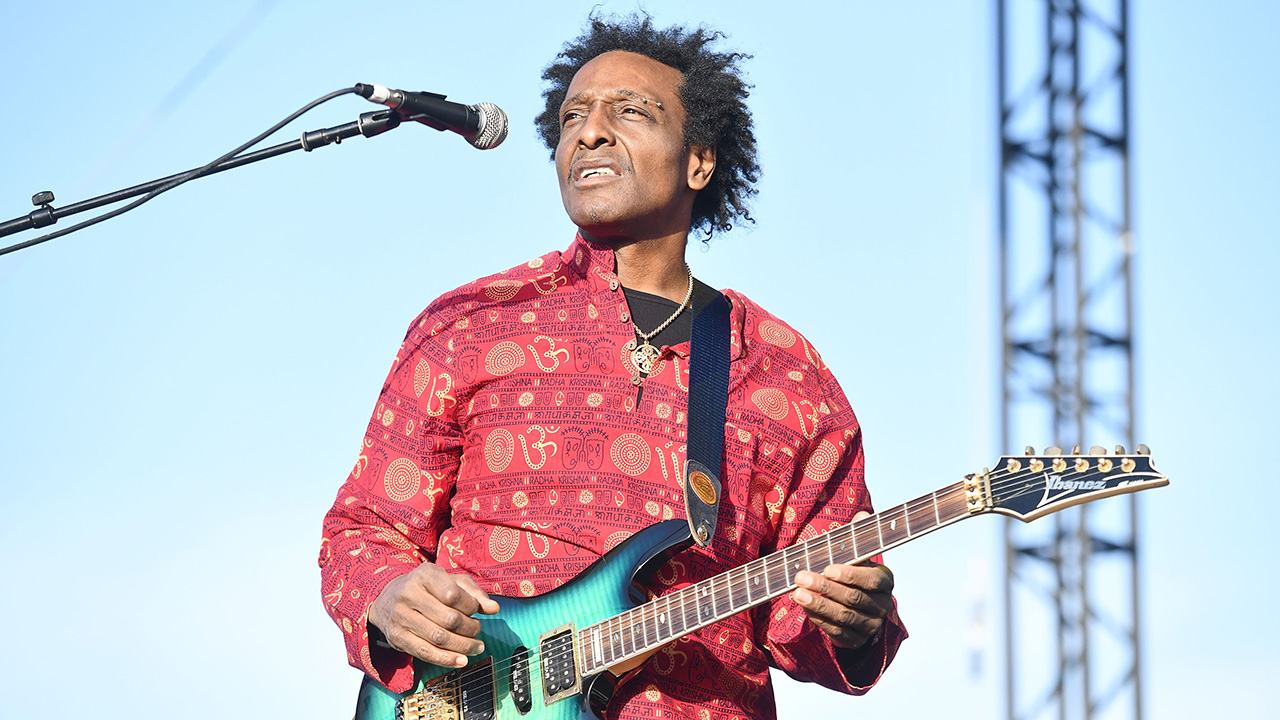

If you’ve ever spent lazy summer days digging classic Bob Marley cuts like No Woman, No Cry, Natty Dread and Revolution, you’ve feasted on the slow-burning, jazzy licks of Al Anderson.

With origins in New Jersey, he was born to create music. Looking back, he tells Guitar World: “My father was a bassist, and my mother played piano. And my father got a call once to sit in with James Brown for a few nights while James played in Northern New Jersey.

“I had good ears, and I could hear all the chords and the lines my mother would sing. My father said my uncle and cousin were great guitar players but weren’t into it. The first instrument I ever put in my hands was my father’s bass, and from there I was off and running.”

Reggae couldn’t have been farther from his mind in the ‘60s: “I got into trombone for a while, but I didn’t like it much because there were a lot of positions, and it was a lot of work, and all that saliva was nasty,” he laughs. “So my cousin said, ‘Hey, man, why don’t you keep trying with the guitar?’

“He taught me some chords and then got me into a country program on television from Nashville featuring Roy Clark. I immediately understood Roy, which influenced me to keep playing.”

Soon, he began gigging around New Jersey before moving to London and meeting producer Chris Blackwell, who invited him to play on Bob Marley’s Natty Dread (1974). Anderson’s jazz-rock leanings merged with The Wailers’ breezy vibes created a sound that would rocket Marley to international fame.

According to Anderson, he completed his work on Natty Dread in “45 minutes to an hour” and wasn’t immediately asked to stay on.

“About a week went by, and they liked what they heard,” he says. “They met to talk about where Bob wanted to take his music, and they knew he would have to fill the spot of Peter Tosh, who had vacated the guitar position.

“I wasn't so sure. My son had just been born. I didn’t want to go to Jamaica – but they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. I didn’t have much income and wanted to give my son a better life.”

He featured on classic concert recording Live! (1975) before detouring with Peter Tosh, then returning to Marley’s band for Survival (1979) and Uprising (1980). He stayed until Marley died in 1981 from malignant melanoma.

These days, Anderson keeps busy with The Original Wailers, which he formed in 2008 alongside other alumni. “It’s incredible,” he says. “The direction we’re going is a destination in and of itself. It’s like world music. It’s a jam band, but with an amazing selection of songs.

“We don’t play the songs like we once did, but the soul is there because it’s the stuff we created in the ‘70s. We play the catalog and do some of our stuff, which acts like a mirror between then and now.”

What were your early gigs before Bob Marley like?

“I had this group that was like Bread – we played at nightclubs in South Jersey, where you could play three sets a night. I was young, like 17, and snuck into these places. But it was cool because I got about $500 a week to play cover songs, like Mustang Sally and My Girl.”

From there, you moved to England, right?

“Yes. To that point, my teachers taught me to be a rhythm player. I wasn't free to play solos, which was tough because I wanted to play improvisational jazz after George Benson changed my world. When I was 19, I left. America was a drag then, man. There wasn’t enough substance.”

How did you end up in the studio for Marley’s Natty Dread?

“I got a job with Island Records and got to know Bob’s producer, Chris Blackwell. He calls me and says, ‘Hey, could you play on the Natty Dread sessions?’ I had never really heard Bob’s music, so I didn’t have a clue. The reggae scene was different. It was hip and a melting pot of African, Jamaican and English influences from that time.”

Did your lack of familiarity help you bring a fresh perspective?

“Absolutely. I had no idea what I was getting into because that music was alien to me. So, I walked into the studio with my guitar, met Bob, and just started playing. After I’d finished up in the booth, I met him again, and he said he didn’t want to hear the jazz-rock stuff I was doing.”

Did Bob give you any direction?

“He said, 'That's not it.’ So I played some more laid-back stuff that I thought would work. They played Concrete Jungle, which has a section where Wayne Perkins takes a fantastic solo, and I said, ‘That’s the sound. I’m gonna try and do that, but still do what I do.’ Bob said, ‘Yes, more blues, and add some salsa,’ so my playing sounded like a slower, more riff-filled version of country music.”

Sounds like a steep learning curve.

“It was. I had to start all over again; I needed to play much slower and add more feeling. Once I did, I said, ‘Yeah, this is what they want,’ and Bob told me, ‘Yeah, cool. That’s it, man!’ A big help was listening to No Woman, No Cry; I came up with the first solo, where it’s quiet and has interesting chord changes.

Soon after, you officially joined The Wailers. What was that experience like, given that Natty Dread hadn’t broken yet?

“They promised me that if I went to Jamaica, they’d get me a hotel and a car – but that never happened. I didn’t have any money, but the thing was, Bob didn’t have any money either. He spent all his money on recording and traveling, and his expenses were very high.

“When I first got down from London I was knocking on hotel doors, but there was no room for me. I got there with almost no money, a guitar, and one suitcase, and I ended up sleeping outside on a lawn chair with my guitar on the beach. It was rough, and the mosquitos fucking destroyed me.”

But you stayed and ended up going on tour.

“I didn’t see Bob for the first few weeks in Jamaica. And honestly, the whole first year was a nightmare. There was no food, no money – but I stayed. We didn’t rehearse much; we just hung out, drank juice, and ate porridge and fish.

“Before we even went out and played shows, I got sick. There was a lot of sleeping on pieces of cardboard with a blanket. Like you said, this was before Natty Dread came out, so there was no money.”

Of course, Natty Dread was a huge success. How did that change your fortunes?

“Every song I played on went to the top of the charts. Bob was becoming popular, but there was still no money. It took months to get the royalties, let alone the small crumbs I was promised. But don’t get me wrong – I would, if I had to, do it all over again. Bob’s songwriting had natural substance, like, an abundance of substance.

“I had never seen a guy who had so many people around him. Bob was observant, could read people’s energy and spirit, and put that into his music. I’ve never seen an artist like Bob – he could take negatives and make them positives. But it was weird because I went from making $500 a week as a kid to being in Bob’s band and having nothing.”

After Live!, you left to play with Peter Tosh, but later returned to Bob’s band, which now also featured Junior Marvin, who had replaced you. What was that like?

“Junior Marvin was told what to do when he joined. If you listen to his versions of Waiting in Vain or No Woman, No Cry, they’re exactly as I played them. But let’s be clear: he never liked me. I had such a bad experience with him and never said anything. I hate to say it, but Junior wanted to be me after I left Bob’s group – he even got the same guitar and hair.”

It must have been difficult locking in with him musically.

“It was impossible. Whatever I was doing, Junior was a complete copycat. And I don’t like copycats. I won’t say I hate him; I forgive him for many things I won’t get into.

“But it was very degrading and a mind-fuck, because he’s like five years old than me. I was young and didn’t want to play games. If you watch many old performances, I stayed away from him. And that’s because I couldn’t take what was going on.”

Are those issues why your contributions to Survival and Uprising were limited?

“The producer [Alex Sadkin] said, ‘I’m gonna get Junior to play lead,’ and I said, ‘Well, fine,’ and I left the studio. I played on two or three tracks from Survival, but he wanted Junior. I knew what to do, but he was squashing me in a corner, so I stayed away.

“Survival is excellent, but it has a different sound. It was tough; I just tried to fit in wherever possible. And if the other guy wanted to play guitar, that was fine; he could do whatever he wanted. I wasn't going to compete with him.”

Bob Marley is often unfairly boiled down to someone smoking a joint on a poster. What’s your take on Bob’s legacy in retrospect?

“Bob was a lot more than that. People are still fascinated by Bob Marley and The Wailers. But to me, it’s not just Bob – it’s Peter Tosh, it's Bunny Wailer; it's all of them. If people knew the whole truth, their perception would change. But Bob deserves everything. He sacrificed his life for his country and philosophy.

“But sadly, they made record and management companies and lawyers a lot of money. They were ripped off, but people don’t know that. Bob deserves so much credit, but all three are equal. It’s not about one; it’s about the trinity and their synergy. They're equal… but not all men are created equal in this world.”

You've kept the legacy alive with The Original Wailers. Where do things stand there?

“Before Bob passed he told me, ‘Don’t copy me. Don’t get a guy who’s going to go out there, act like me and copy me.’ So we don’t try and be like him; we found ourselves.

“But I’m pouring my heart out, and we went through many changes while trying to bring people together and play this music. A lot is happening, and new music is coming. But it’ll take some time to get to a place financially where we can keep it moving forward.”

- Keep up with Anderson’s progress via The Original Wailers website.