Bob Dole was one of the most durable and dominating figures in the American politics of his era. He was also a profile in courage, an object lesson of how, however humble one’s background, whatever the obstacles life throws up, there are few that sheer determination and cussedness cannot overcome.

The most salient fact about Dole is not his long service on Capitol Hill, nor his skilful leadership of the Republicans in the Senate, nor even his four attempts at national office – once for the vice-Presidency and three times for the White House itself. His defining moment came in April 1945 in northern Italy, when the 21-year-old infantryman led a charge against a fortified German position near the village of Castel d’Aiano in the hills above Bologna.

Dole was so badly wounded in the action that he was not expected to live. A medical orderly gave him morphine on the battlefield, marking a letter M on his forehead with his blood. Though he did survive, it was only after years of rehabilitation, paid for in part by donations from his fellow citizens of Russell, Kansas. While undergoing treatment at a Michigan hospital, he almost died for a second time, as a result of a blood clot. His weight at one point plunged from 88kg to 55kg.

He lost the use of his right arm forever, and was forced to learn to write with his left. Later, Dole would insert a pen between the fingers of his right hand to prevent people from shaking it. For the rest of his life, even simple acts like getting dressed would cause physical pain.

And yet Dole rose almost to the summit of US politics. For eight years he was the senior Republican in Washington. Over the years he moved from the right to the centre of his party. He had little in common with the East Coast grandees who once ran the party. Neither though was he one of those brass-plated conservatives who came to dominate it in later years. He was above all a man from the plains, a product of the sparsely populated American heartland, where men are tiny creatures indeed, on endless prairies beneath endless skies.

The Dole family house is today signposted in Russell, the small wheat and oil town in Kansas where he was born. “Anyone who wants to understand me must first understand Russell,” Dole later wrote. “It is my home, where my roots lie, and a constant source of strength.”

Throughout his life, Dole was a “doer”. His war wounds put an end to his childhood ambition of becoming a doctor. Instead, having completed the education with a belated law degree, he entered Kansas politics, winning a seat in the Kansas state legislature before becoming attorney for Russell County. By 1960, he was elected to the first of four terms in the House of Representatives. Eight years later, Dole captured the Senate seat he would hold for more than 27 years.

The young Dole was a hard-edged operator, whose natural combativeness often turned to bitterness. By the mid-1970s he had the reputation as a Republican hitman, saying out loud what others in the party privately thought. After Gerald Ford had picked him as his running mate in 1976, Dole even used his vice-presidential debate with Walter Mondale to suggest that the Second World War, Korea and Vietnam were “Democratic wars”.

In 1980 Dole made his first bid for the top prize, only to be knocked out of the contest by Ronald Reagan during the early primaries. Eight years on, he seemed to have a better chance against George HW Bush But having won the Iowa caucuses, Dole faced Reagan’s sitting vice-president in a TV debate a few days before the crucial New Hampshire primary. “Stop lying about my record,” he snapped before a national TV audience. Bush in fact had misrepresented Dole’s views on taxes. More important, however, the Kansan’s dark side was there for all to see.

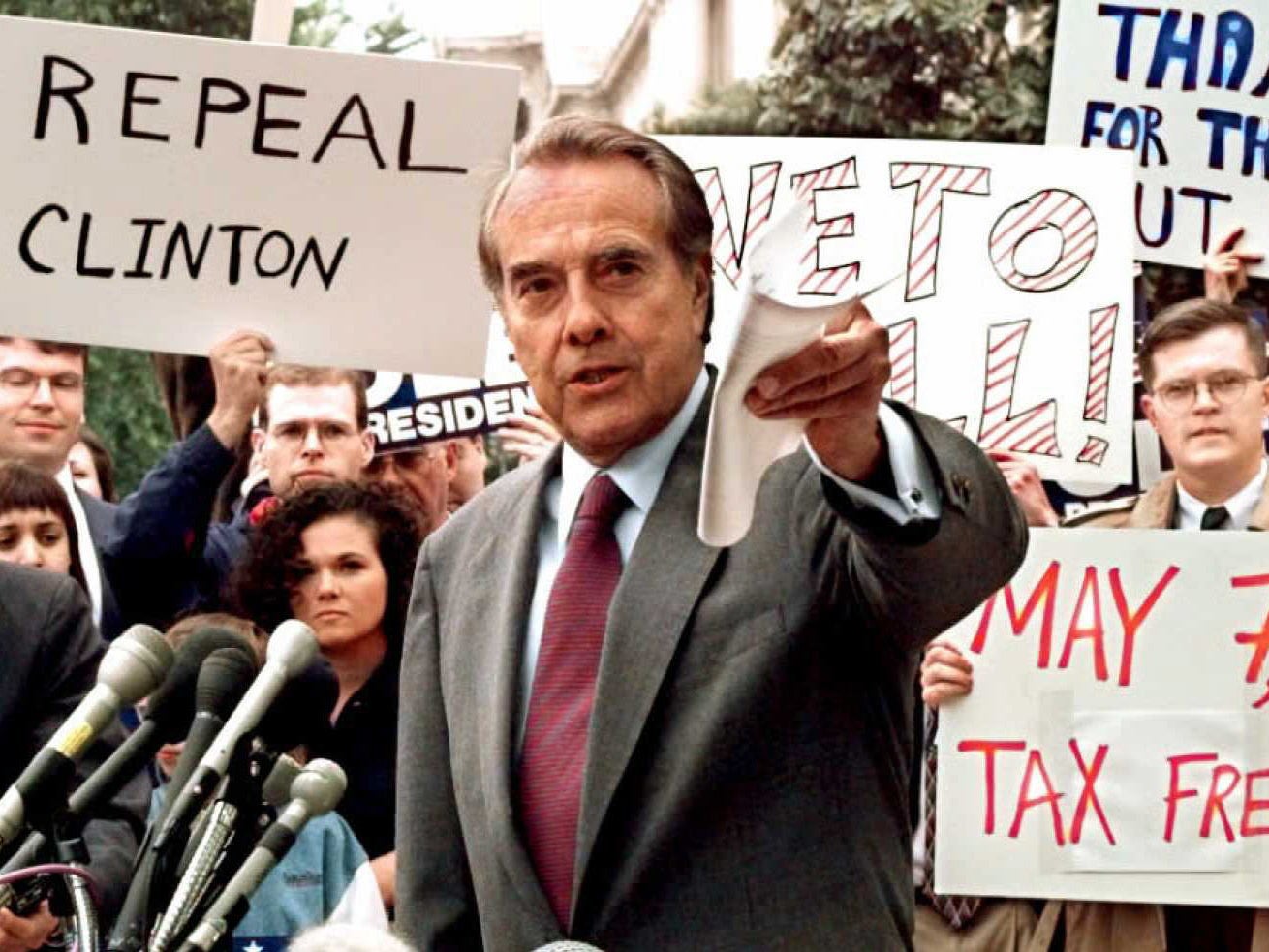

By then, Dole was Republican leader in the Senate, a towering figure, and after Bill Clinton’s victory in 1992, the party’s de facto spokesperson in Washington. In 1996, he might have been 73 (and showing his age), but the nomination was his for the asking if he wanted it. Dole did want it, and the crown was duly bestowed at the San Diego convention in 1996.

His acceptance speech, painted in sepia hues and harking back to the vanished America of the war-time “Greatest Generation”, set the contours of the campaign. Defeat was not entirely his fault. Bill Clinton had recovered his poise, while the independent candidate Ross Perot was again eating into the Republican constituency.

Unlike Clinton, Dole was anything but an inspirational campaigner. He was no orator, while a gritty upbringing gave him a clear sense of the limitations of the human condition. Nor, endearingly, could he hide his contempt for many of the antics a candidate was supposed to get up to.

Above all however, the elderly senator came across as yesterday’s man, the antithesis of the youthful, high-tech-savvy “Bridge to the 21st century,” that was Clinton. Late night hosts would joke how Dole was so set in his ways that he insisted on being back in Washington after a day’s campaigning before 10pm when Reagan National Airport closed, so that he could sleep in his own bed. To no one’s surprise he was soundly beaten on 5 November 1996, by 49 per cent to 41 in the popular vote, and by 379-159 in the electoral college.

If that campaign was quickly and deservedly forgotten, Bob Dole the politician would be remembered for two things. One, naturally, was his 11-year-stint as Republican leader in the Senate. Gradually, the old slash-and-burn Dole gave way to a more nuanced and conciliatory figure. On occasion he could be brutally partisan, and was always a tough negotiator.

But once given, his word was his bond. Whatever the divisions of policy or personality, he maintained a good working relationship with Republican and Democrats alike. Dole was not one for the big picture. But he was a master of tactics, acutely aware that politics was the art of the possible.

Dole’s second and increasingly famous legacy was his wit. Not for him the treacly banalities in which American politicians are wont to indulge. His jokes were laconic, acerbic and often self-deprecating. He had an odd habit of referring to himself in the third person, “Bob Dole thinks...”

In typical style, as he surveyed a thin turnout for a post-election speech, he remarked that “we only invited people today from the states we carried. We didn’t want too big a crowd.” Dole even compiled a couple of decent books on the subject, Laughing (Almost) All the Way to the White House, and Great Presidential Wit.

Remarkably, Dole even established a warm and droll rapport after the election with his conqueror Bill Clinton. “I, Robert J Dole, do solemnly swear,” he began his reply when Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom shortly after the 1996 election – before deadpanning: “Sorry, wrong speech.” Later the two briefly even had their own joint political commentary slot on network TV.

By now Dole was little short of a listed national monument. With grace and humour, he carried out the unaccustomed role of supportive spouse to his wife Elizabeth, thrice cabinet officer under Presidents Bush and Reagan, Republican presidential candidate in 2000 and North Carolina's first female US senator from 2003 to 2009.

In 2018, Dole received the Congressional Gold Medal in recognition for his service to the nation as a “soldier, legislator and statesman”. Congress also unanimously passed a bill in 2019 promoting Dole, then aged 95, from captain to colonel for his service during the Second World War.

He is survived by his wife and daughter, Robin Dole.

Robert Joseph Dole, US politician, born 22 July 1923, died 5 December 2021

Rupert Cornwell died in 2017