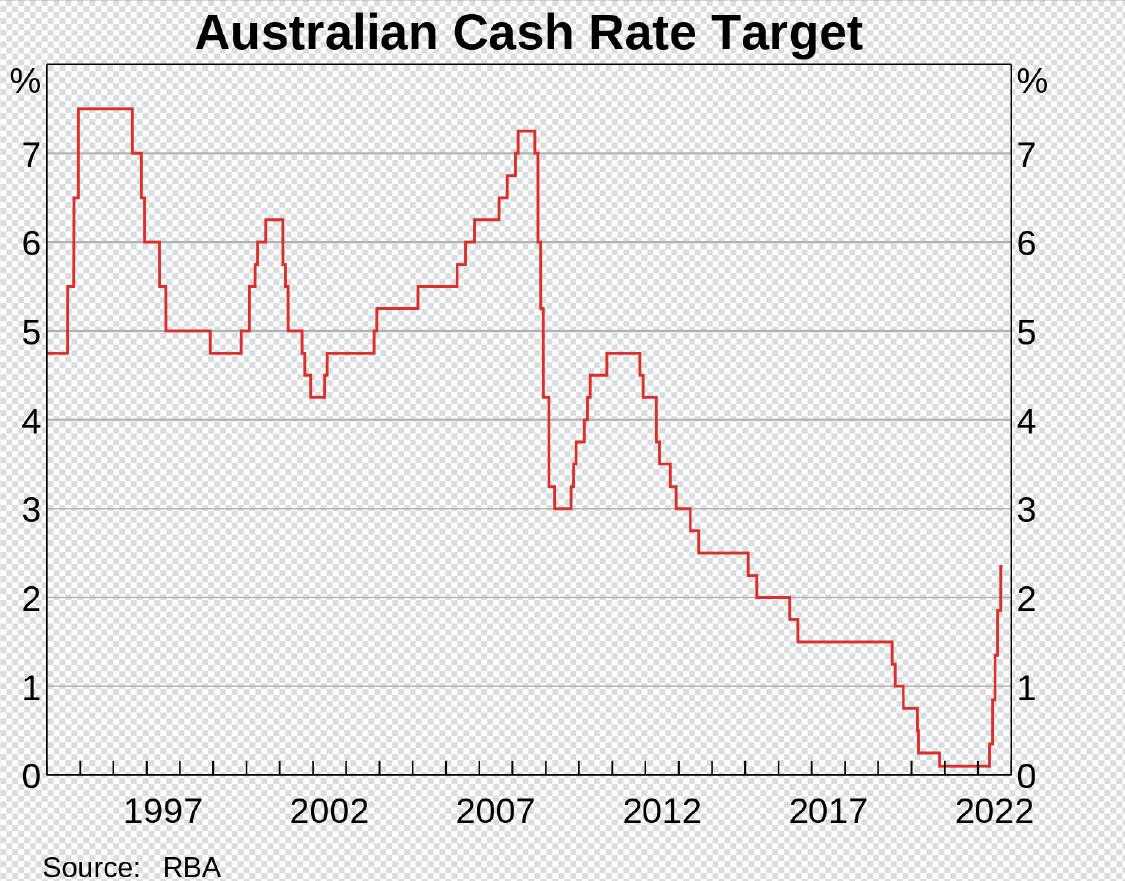

THE Reserve Bank of Australia has lifted interest rates for the seventh consecutive month, a 0.25 percentage point rise taking the cash rate to 2.85 per cent.

It was a smaller increase than some were expecting, but there is ample evidence to suggest that monetary policy will continue to tighten.

Official rates in most developed economies are still low by historical standards.

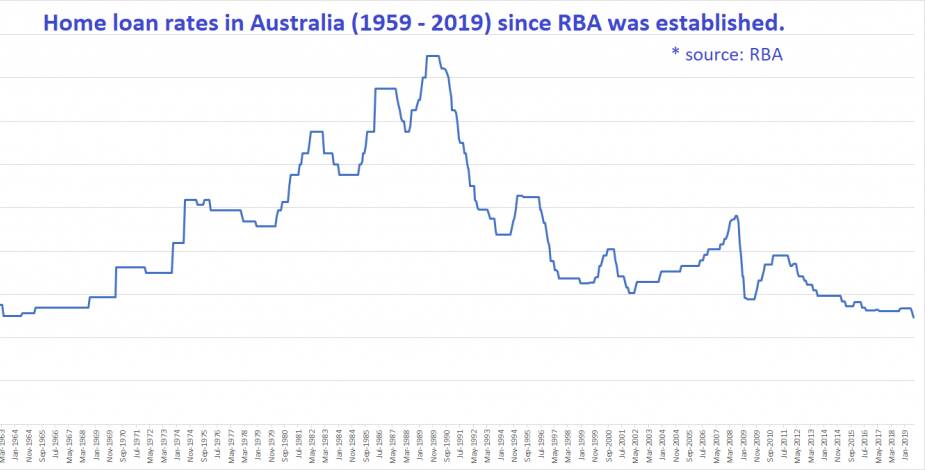

In the wake of the 1987 stock market crash, Australian interest rates hit an all-time peak of 17.5 per cent in January 1990, triggering the downturn that then-treasurer Paul Keating infamously dubbed "the recession we had to have".

Rates fell quickly afterwards. After a short-lived increase in the mid-1990s, they continued their descent to record-breaking lows, with some countries entering the previously unimaginable territory of negative interest rates.

But now, with the aim of curbing the post-COVID global return of inflation, interest rates are on the rise across the globe, and any reasonable assessment of the economic outlook includes more thunderstorms and lightning than blue skies and sunshine.

Interest rate impacts take months to work their way through any economy. On one hand, the Reserve Bank faces pressure to lift rates hard and fast to curb inflation.

On the other hand, the potential for a hard economic landing and a recession provides a counter argument to move more slowly.

For individuals and households, interest rates are an unavoidably blunt tool.

Rates are not rising this time to rein in galloping house prices.

Inflation, as noted earlier, is the target. Estimates vary but as much as half of Australia's national wealth is tied up in housing.

Some 3.3 million owner-occupiers owe about $1.3 trillion in mortgage debt. About 2.9 million households live in rented properties and the owners of these - many of them "mum and dad" investors - owe another $700 billion.

Whether it's the sharp nail of increased mortgage repayments, or the hammer blow of job losses as rising interest rates slow the economy, the bulk of the pain is felt by everyday Australians working as best they can to keep a roof over their heads.

Then there's our superannuation.

Indebted as we are as a nation, workers are also savers now, and our superannuation balances will rise and fall with the broader market.

In the end, everything swings on a finessing of interest rates, to tame inflation with the least possible collateral damage.

ISSUE: 39,743

WHAT DO YOU THINK? We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on the Newcastle Herald website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. Sign up for a subscription here.