A big part of what makes them an enjoyable media hub is the superior sound we've come to expect from them. Whether you listen through the built-in speakers or a pair of the best wireless headphones, things sound great.

But not everyone is into audio, and there are so many odd-sounding words and abbreviations and secret codes getting thrown around. Of course, you don't have to know all of the different Bluetooth audio codecs or what any of them mean to enjoy the music, but we all want to know what we're reading or hearing. So let's dig in and check out what some of the most common things you'll hear actually mean!

General terms you need to know

There are a few terms you'll see in every audio discussion. And like every other audio term, they really don't mean what it seems like they should mean sometimes. So here are the basics to get you started so you can keep up with just about any audio talk.

Bitrate:

The number of bits of data that are processed per unit of time. When talking about audio, that rate of time is usually measured in seconds as bps (bits per second). Standard SI-prefixes apply (not Binary Prefixes), so kbps (kilobits per second) = 1,000 bps, Mbps (megabits per second) = 1,000 kbps and Gbps (gigabits per second) = 1,000 Mbps. A higher number means more data is being processed, so audio will sound better.

Bit:

The way audio bit depth is written. Bit depth is the number of bits of information included in each individual sample (see Hz below). For example, CD audio uses 16-bits per sample, while DVD audio uses 24-bits per sample. Hi-resolution audio players will also be able to play 32-bit audio, and this includes some specialty phones like the old LG V series.

Container:

A metafile format that controls and describes how multiple types of data exist inside a single computer file. A good example of this difficult idea is an MP4 file. An MP4 file can hold encoded audio, encoded video, metadata like subtitles, lyrics, and album art in any combination.

A container doesn't decide how its data is encoded, so you might be able to open an MP4 file and be unable to play back any of the data without the proper codecs. Yeah, it's kind of a mess and impossible to describe without using computer-speak. All you need to know is that audio containers hold encoded files, and you'll need the proper codec installed to play any of them.

Codec:

Software (we'll leave hardware codecs for another day) used to encode and decode digital data. Codec is short for encoder-decoder. The encoder translates data and gets it ready for some sort of transmission, and at the other end, the decoder reverses the encoding. MP3 is a popular audio codec.

Applications like Audacity can use an MP3 coder to encode music into a .mp3 file, and your favorite audio player uses an MP3 decoder to turn it back the way it was and play it.

Compression:

Popular codecs compress an audio file while encoding it to make it smaller and easier to transmit. This is the same concept a .zip file uses to crunch down the contents of a folder. Ideally, you want an uncompressed file to be a bit-by-bit copy of the original, but most compression algorithms discard data that won't drastically change the way the audio sounds. Or at least they try to.

DAC:

A Digital to Analog Converter that turns computer bits (the digital) into sounds (the analog) that can come through a pair of headphones. Every device that can play digital music has a DAC, as does every pair of Bluetooth headphones. Some just have a better DAC than others and are able to create cleaner analog audio from the digital source.

Dolby:

A company that specializes in noise reduction and audio encoding. Dolby licenses its tech to several phone manufacturers.

Hz/kHz:

Hz is the abbreviation for Hertz, which is a unit of measuring time. When talking about digital audio, you'll usually see it measured in kHz (kilohertz). It designates the sampling frequency — the number of times the audio is sampled (analyzed and recorded) per second. Landline phone audio is 8kHz. VoIP telephones are 16kHz. Audio CDs are 44.1kHz. This continues all the way up to 5,644.8kHz, which is Philips and Sony's Double-Rate DSD (Direct Stream Digital) format and is absolutely insane.

Generally, the higher the sample rate, the better the audio will sound, but there are diminishing returns once you pass the upper limit of what most people can hear.

Lossless:

Lossless is a type of audio compression that can create an (almost) exact copy of the original when a file is uncompressed. FLAC and ALAC files are lossless.

Lossy:

Lossy is a type of audio compression that rebuilds an "approximation of the original data" but compresses the data into a smaller file. MP3 files are lossy.

Bluetooth profiles

Bluetooth has its own slew of audio-related terms, and they are equally important as most phones don't have an analog headphone jack. It gets its own section, so we can break a few things down.

Bluetooth profiles are a set of specifications that both the source (the device sending the audio like your phone) and the destination (the device that receives the audio like your favorite headphones) know what each other can do and how to work together and stream audio to your ears. Even the Bluetooth earbud of old needs a Bluetooth profile to connect, and this is the only way to make everything work.

HSP (Headset Profile):

The HSP profile is required for basic headset operation. It has very limited remote control capabilities, and the audio quality is 64 kbps (mono) maximum.

HFP (Handsfree Profile):

HFP is an advanced version of HSP that's also designed for headsets (not headphones). It provides redialing and voice dialing through remote control. HFP version 1.6 uses a mono configuration of the standard SBC codec. See the codecs section below for details.

A2DP (Advanced Audio Distribution Profile):

This profile was designed for stereo audio for things like multimedia. This is the profile your headphones (not a headset) need to use.

AVRCP (Audio/Video Remote Control Profile):

AVRCP is used with A2DP to provide a remote control for things like play/pause or track skipping. Versions 1.4 allow for full volume control of both devices, while lower versions control the volume of the headset only and not the source.

If you want to use Bluetooth earbuds or the like to take calls and don't care about other audio, you need a device that uses HSP, but you want a device that uses HFP, so you have more control.

If you want to also listen to music through a stereo Bluetooth device — headset, headphones, portable speaker, etc. — you want both A2DP and AVRCP for the best experience.

Bluetooth audio codecs

Bluetooth audio codecs don't have to be Bluetooth only. They are encoding and decoding instructions that the right encoder and decoder use to take raw audio, turn it into something better for transmission, and then turn it back into raw audio once it reaches your headphones. You can't play any audio without the right encoder and decoder, so support for audio codecs is pretty important.

You'll usually find information about what codecs a pair of headphones can use in the box they came in, and you'll find information about the codecs your phone can use in the manual or on the manufacturer's website.

SBC (Subband Coding):

This is the default A2DP codec and the minimum required for stereo audio. Every stereo Bluetooth device must support SBC because it's the failsafe fallback if no other codec matches both the source and destination hardware. It provides an uncompressed stereo audio stream of up to 328kpbs at 44.1 kHz. Because it's not compressed, there is no need for the target (your headphones) to decompress it.

It does tax Bluetooth's limited bandwidth and is subject to skipping or buffering (depending on your source) when conditions aren't ideal. There are several "levels" of SBC (low, medium, and high), and the quality is determined by the source device.

AAC (Advanced Audio Coding):

This is the same AAC encoding you'll find for music that's not streamed wirelessly and is what iTunes uses. It provides better audio than MP3 compression at the same bitrates and can rival lossless files in quality. Most headphones don't include AAC, but high-end models designed for use with the iPhone or iPod will, and they transfer data at 250 kbps.

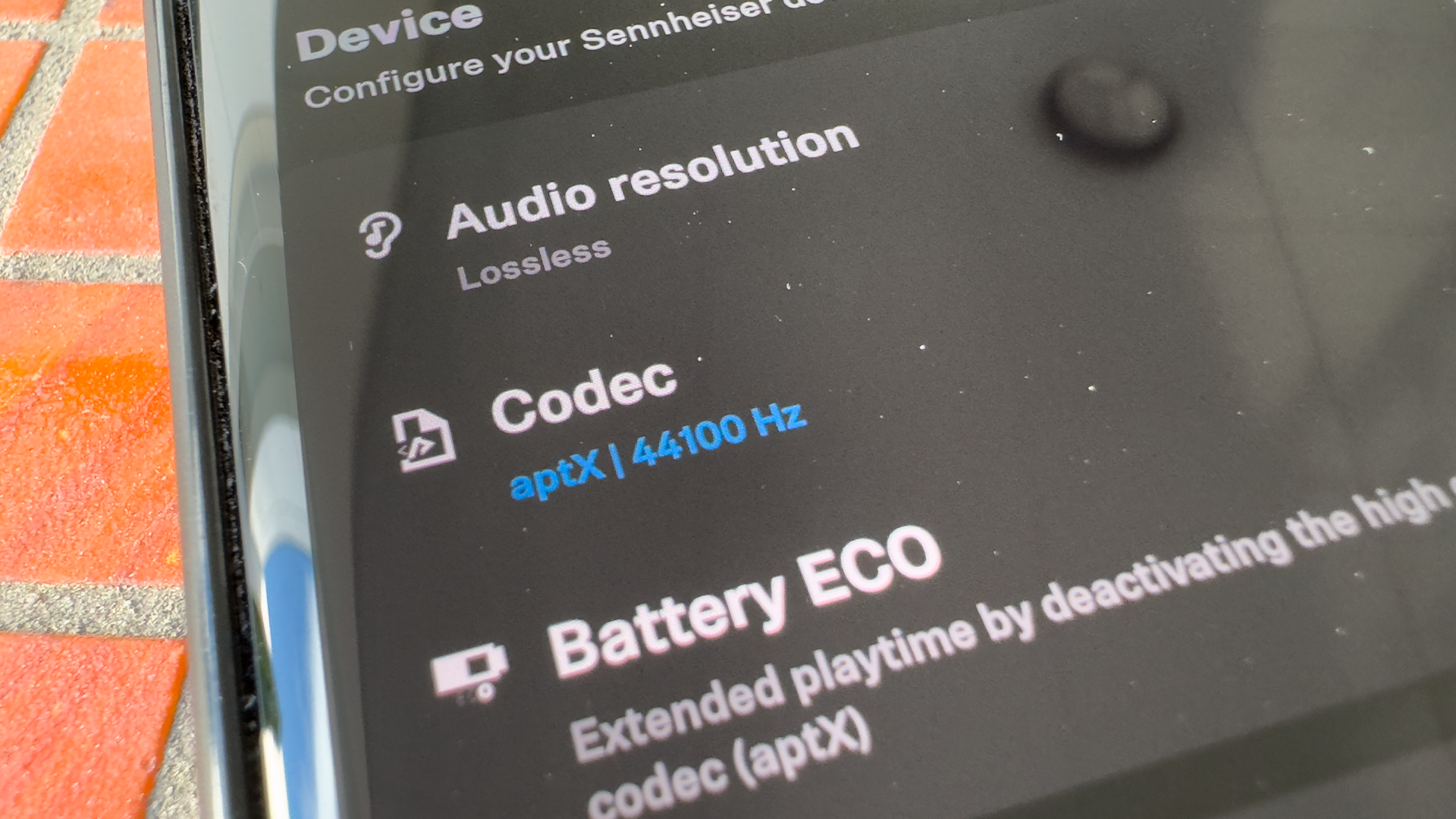

aptX:

aptX is a proprietary audio codec developed in 2010 by APT (hence the name) to provide higher-quality audio than SBC can deliver. It encodes a CD-like quality (16-bit / 44.1kHz) audio stream using a more efficient audio encoding (compression, much like the .mp3 codec) and a higher data transfer rate of 352kbps. aptX is not required for stereo audio, and you'll find a lot of equipment doesn't include it.

That said, there are a few different versions of aptX:

- aptX LL: This is a version of the aptX codec designed for especially low latency. It's used in devices like gaming headsets that value low latency over quality but still provide audio comparable to SBC. aptX LL can transmit stereo audio with latency as low as 32 milliseconds, which is faster than we can process, so it appears to be latency-free.

- aptX HD: This is a version of the aptX codec that uses newer and better compression methods and higher data transfer rates (576kbps) to deliver 24-bit / 48kHz stereo audio. the compression algorithms have been designed to inject very little noise, and aptX HD streams approach lossless hi-resolution audio in quality.

- aptX Adaptive/Lossless: Qualcomm released the adaptive version of the codec in 2018, and at that time, it was only capable of scaling from 279kbps to a 420kbps max bit rate. In late 2021, Qualcomm released an update to adaptive, which it called "Lossless," and is a version of the aptX codec that scales bit-rate based on environmental interference and supports up to 24-bit 96kHz playback with lossy compression. It also features low latency for gaming and voice calls. Initially, the Adaptive version was focused on delivering CD-like quality, but with the introduction of Snapdragon Sound with aptX Lossless, Qualcomm promises “it retains all of the original content, bit-for-bit, resulting in music identical to the original recording.” Being the first codec to claim fully lossless Bluetooth audio, aptX Lossless purports to deliver playback of CD-quality audio (1411kbps) files by being able to achieve a theoretical bit rate of over 1Mbps. It should be noted that Snapdragon Sound is an umbrella name that includes Bluetooth radio components and optimized software to ensure the type of connections between source and receiver, which can sustain aptX Lossless quality audio streams.

LDAC:

This is an audio codec designed by Sony to deliver "true hi-resolution" audio over Bluetooth. It can transmit audio at a maximum of 24-bit / 96kHz at speeds up to 990kbps. Like SBC, it has three settings: low (330kbps transfer speeds), medium (660kbps transfer speeds), and high (990kbps transfer speeds). Sony claims LDAC can transmit audio playback up to 24-bit / 96kHz without any downsampling (lowering the sample rate in Hertz) at the source. LDAC on our phones has been supported since Android Oreo, but not a lot of headphones do right now.

LC3:

This codec is a part of the Bluetooth LE Audio standard and is designed to be more efficient at transmitting audio. Those efficiencies show up in battery consumption, audio quality, and lower latency. According to the Bluetooth SIG, it should provide higher-quality audio at the same data rates as the older SBC codec which is a part of the Bluetooth Classic standard. Unlike aptX, manufacturers don’t have to pay a licensing fee to use it, so it could lead to cheaper products if widely adopted.

SSC:

The Samsung Seamless Codec features a variable bit-depth and has some sample rate improvements to its initial release when it was called the Samsung Scalable Codec. It now supports a 24-bit/48kHz–sample rate, so technically, it is capable of streaming Hi-Res audio. This codec is exclusive to Samsung devices and works only with Samsung Galaxy Buds paired to a compatible Samsung phone running One UI 3.0 or later. For 24-bit audio playback, you’ll need the Galaxy Buds 2 Pro and a Samsung phone running One UI 4.0 or later.

LHDC/LHDC-V:

The acronym here stands for low latency and high-definition audio codec. Version 5 (LHDC-V) is able to deliver 24bit/192kHz sample rate transmission, and scales from 128kbps to 1Mbps (1000kbps) based on environmental factors which places it in competition with LDAC.

Audio file types

There are hundreds of audio coding formats. Some are specialized, like aptX for Bluetooth or ATRAC for the PlayStation or Walkman, but there are a handful of standards you'll find on portable devices like your phone. Most of the time, the format defines the file type — MP3 format audio uses a .mp3 file extension, AAC audio uses a .m4a file extension, and so on. Audio coding formats need to be supported by the player software, not your device itself, but for many, your device must have a license to use them.

AAC (Advanced Audio Coding):

This format is also a standard Bluetooth audio codec, though not very popularly supported. It supports audio compression with little data loss, so audio sounds are clearer than MP3 but still have comparable bitrates. This is the native format your old iPod uses, and some audio players can play it through an MP4 container with the .m4a file extension.

ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec):

Developed by Apple as a lossless audio compression format, ALAC is now open-source and royalty-free. It delivers eight channels of audio at 16, 20, 24, and 32-bit depth, with a maximum 384kHz sample rate. ALAC is also stored in an MP4 container with a .m4a file extension, but it's not the same lossy compression used with AAC.

FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec):

FLAC is an open and royalty-free audio codec that supports 4 to 24-bit audio at any sampling rate between 1 Hz to 655.35kHz on eight channels. FLAC is capable of compressing an audio file by 60% and still have an exact copy when uncompressed. Files using the FLAC coding format have a .flac extension.

MP3 (MPEG-1 or MPEG-2 Audio Layer III):

MP3 is a lossy codec that can shrink CD quality (1411.2kbps) audio by up to 95% and provide comparable quality when uncompressed at playback. There are various sampling and playback rates, and the higher the number, the better it will sound. The MP3 codec intelligently reads audio files and discards data that we won't be able to hear during compression and encoding. You'll find .mp3 files just about everywhere, and almost any player can play them back.

Vorbis/Ogg:

Ogg is an open-source container format that can multiplex independent streams for audio, video, text (subtitles and lyrics), and metadata. It can house numerous audio coding formats, but the most popular one you'll see on your phone is Vorbis. Vorbis is an open-source audio format that can encode source material from 8kHz to 192kHz with a maximum of 255 channels and create output files between 45 and 500kbps. Files with the extension .ogg are native to Android and play through the system's default player or any number of third-party players.

WMA (Windows Media Audio):

WMA is an audio codec that consists of four separate audio codecs: WMA, WMA Pro, WMA Lossless, and WMA Voice. WMA was developed by Microsoft to compete with MP3 and covers the spectrum from single-channel mono audio with WMA Voice (it's actually important to handle this type of audio in a special way) to 24-bit / 96kHz using six discrete channels. The compression ratio for music varies between 1.7:1 and 3:1. All WMA-encoded files carry the .wma extension and are supported by third-party players.

The most important part

You don't need to know any of this to enjoy listening to your music through your favorite headphones, and that's what really matters. Like everything else, some people will care and will debate about individual products until the end of time, and that's because they enjoy the underlying tech and how it works. Neither group is right or wrong, so don't feel left out if this just isn't your thing.

Just know that audio from our phones is getting better, the companies who make headphones are making better ones, and the music you love today will sound just as good, if not better tomorrow.

Rock on!