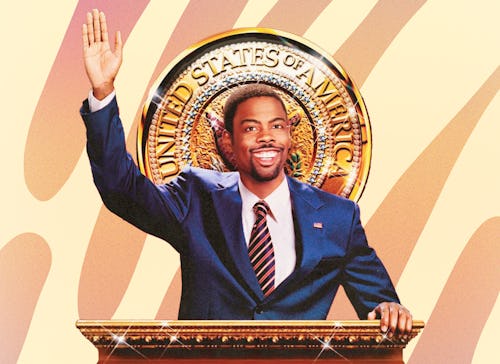

Extreme political ad attacks. A nationalist candidate with celebrity ties. Political machinations of a “progressive” party. These things are all commonplace in today’s hyper-partisan political climate. But when they were plotlines in the 2003 satire Head of State starring Chris Rock, most people thought the film was stranger than fiction.

Less than two years before President George W. Bush’s reelection, Rock played the role of Mays Gilliam, a D.C. alderman and bonafide “man of the people.” His working-class prowess was evidenced in a speech that was impressive then and would still resonate now, a commentary most known for its “That ain’t right!” refrain:

They had a speech written for me about what the people need. But you guys are the people. You know what you need. Better schools, better jobs, less crime. How many of you right now work two jobs, just to have enough money to be broke? If you work two jobs, and at the end of the week, you got just enough money to get your broke ass home, let me hear you say, ‘That ain’t right!’

And now, we got these corporations stealing all the money. They ain’t stealing their money, they stealing our money! The pension. You work for 35 years. You thought you was gonna leave your kids a will, now you gonna leave them a won’t! You show up to get your pension, they give you a pen! They give you a damn pen! Now, what in the hell am I supposed to do with a pen? I should stab you in the neck with this pen, Mr. Pension Taker. Taking everybody’s pension and nobody going to jail. Meanwhile, you or I, we steal a Big Mac with cheese, next thing you know, we on death row!

The speech — much more so than the movie itself, which is laden with heavy-handed stereotypes — spoke to our working-class condition. It was rewarding not only because it galvanized the people, but also because it inspired a progressive campaign derived from Gilliam’s true desire to help. Political polish or puppetry couldn’t deter him.

That said, class distinction isn’t Head of State’s singular hallmark; rather, it’s the way the film unapologetically factors in race, particularly the circumstances of Black people in America. As Gilliam aptly said to elderly community member Mrs. Pearl before the two narrowly escaped a building implosion, “You’ve seen churches burned to the ground; you’ve seen dogs sicced on children; you’ve seen Malcolm X killed, you’ve seen JFK killed; they shut up Muhammad Ali; they shut up Richard Pryor; they gave Magic Johnson AIDS; they turned Michael Jackson white. Now do you really think these people give a damn about you?”

And then there were the scenes that illustrated Senator Bill Arnott’s viewpoint of people of color. Arnott (James Rebhorn) was the political mastermind behind the plan to employ Gilliam as a token candidate. “The minorities will be the majority. The smartest thing we can do is be the first party to nominate a minority for President,” Arnott said in a clandestine speech that outlined the party’s intentions. “Now, we’ll lose, of course, but the minorities will be happy. The minorities will be happy, and they will vote for us in 2008 because we’ve shown we support them. And the white people will vote for us because our guy isn’t Black.”

Through moments like those, we can clearly see the uneasiness Black folks feel when faced with the cognitive dissonance of trusting electoral politics and distrusting the government.

Arnott’s speech was a cold, calculating assessment of a presumably progressive party that ended up being part of the establishment. And it feels even more chilling some 20 years later. Today, as “bipartisanship” looks more like conceding to right-wingers and corporations, progressives like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders are either boxed out of the process or forced to trade their silence for political points. Meanwhile, neither the Democratic or Republican party currently serves the interests of African-Americans, and “representation” becomes vacuous.

Generally speaking, the idea of “representation” is at the crux of Black political engagement. Within lies the promise of Black power, though in the present age, influence is substituted for imagery. We see that in the role of Debra Lassiter, played by the eternally gorgeous Lynn Whitfield. She and Arnott give off strong Biden/Harris vibes, and looking at the movie through that same lens, there might be an inclination to compare Gilliam to former President Barack Obama. At that moment, art teases Black political potential. Can you imagine Obama driving a bus around D.C. to pick up people trying to get to work, the way Gilliam did in the movie? Gilliam stiffed the Teamsters twice during the course of the movie, and still secured their endorsement because of his dedication and ethics. Meanwhile, in the real world, former AFL-CIO leader Richard Trumka apparently wasn’t so impressed by our country’s first Black president. In 2021, just months before his death, he said in an interview that Obama and former president Bill Clinton “didn’t understand the importance of labor.”

Certainly, Rock’s character wasn’t a perfect candidate. His views on spanking children would fall flat in the face of increasing research on how spanking actually increases aggression in young kids. And while many people associate beating children with religion, there are compelling studies and perspectives that refute the practice. With that said, while his views on corporal punishment might be conservative, overall, Gilliam’s political viewpoints translate well to the modern age, with his willingness to discuss gay rights and the need for childcare.

With so much going for this promising Black candidate, only one thing could stand in his way. Not political adversary Brian Lewis, a Trumpish opponent who touted political experience and celebrity kinship (“I’m Sharon Stone’s cousin”) while using a trollish political attack piece declaring “Mays Gilliam For Cancer” that is cartoonish even by today’s standards.

The only thing that could possibly take Gilliam down was white supremacy. It was ironic that Arnott conspired with the opposing party near the movie’s end, after his covert supremacist plan failed. Ultimately, the last-gasp scheme to deter Gilliam would be to tap into the fear of a Black president, and the reason for that unfounded fear is an indictment of America in and of itself. It could be argued that the final white wave of West Coast voters was just trying to “protect their way of life.” Of course, the folks who stormed the Capitol last January said the same thing.

OutKast’s “Bombs over Baghdad” was the perfect song to allude to that intent — the brutal mix of capitalism and imperialism. “God bless America, and no place else,” Lewis repeatedly declared.

Gilliam’s retort cut through the noise, both in terms of Lewis’ policy and the late wave of voter participation: “God bless Haiti. God bless America. God bless Jamaica. …God bless America, and everybody else.”

Revisiting Head of State was like opening a time capsule, and at the same time, the movie revealed a political future that Black folks have not yet enjoyed. The path to get there might be in question, but the passion and purpose required are not. It was fitting that Gilliam’s campaign incorporated some of the rap stylings of Master P’s famous record company – because of his love for working-class people, there was no limit to what he (no, WE) could accomplish.