Who benefits from choice in education? The answer, of course, is everybody—at least, everybody can benefit if they're allowed to choose schooling options that work best for them and their children. That opportunity is perfectly captured by a recent article about black families in Texas who hope to use school vouchers to launch microschools that do a better job than the public school at teaching their children.

When Public Schools Don't Suit Your Kids

Sneha Dey writes in a Texas Tribune article about a push in that state for school choice:

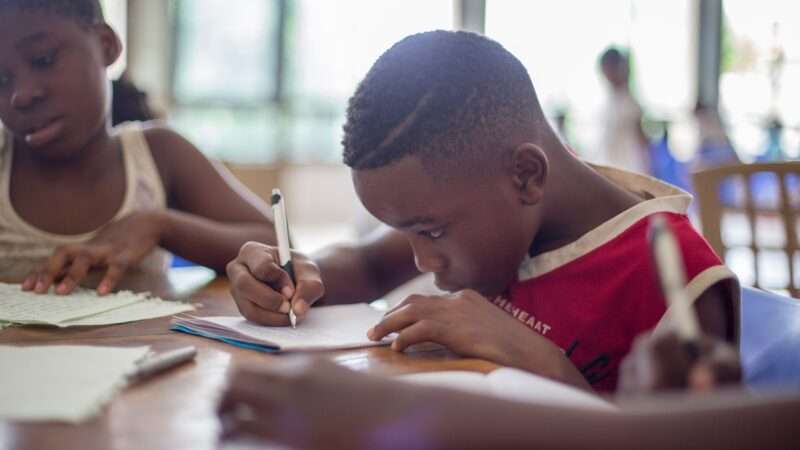

Here in the eastern suburbs of Dallas, three mothers are home-schooling to reimagine education for their daughters. During school days, the girls get in about two hours of core instruction like reading and math, but they also draw, go on nature walks and build fairy villages with the rocks they find.

The mothers say their public schools were not equipped to create a learning space that's wholly safe for Black kids or embraces their culture and identity. Together they create lesson plans to meet each girl's learning needs and adapt their pace when a child is struggling….

The mothers already have spoken with other parents ready to pull their kids out of private and public schools to participate in their collective. But to grow, they say they need the Legislature to create education savings accounts, a voucher-style program through which families could access state funds and pay for private school or alternative education settings.

The model the Dallas mothers want to emulate is that of Arizona's Black Mothers Forum, whose efforts I covered last year in a piece on microschools. The Black Mothers Forum dedicates itself to "tear down barriers to academic excellence due to low expectations, and break the cycle of the school-to-prison pipeline." Like the mothers in Dallas, its founders were motivated by doubts about public schools that are common to many families, as well as concerns specific to their experiences as African Americans.

A Surge in Tailored Education Options

As Dey's piece suggests, microschools span a continuum of education efforts between homeschooling co-ops, private schools, and learning pods. If that sounds a little amorphous, it's because such arrangements are structured to meet the needs of their participants, not to match institutional definitions. In whatever form they take, microschools are increasingly popular across the United States.

"Currently approximately 125,000 microschools exist across the country, reflecting an increase since the pandemic," The Wall Street Journal's Megan Tagami reported in August. "Across the U.S., microschools likely serve between one to two million students."

Dey and Tagami both emphasize that growth in microschools and other DIY education approaches is spurred by programs that make education funding portable so that it follows students rather than being dedicated to government-run schools. That's because many families find it financially difficult to shoulder the costs of education choices on top of the taxes they pay to support public schools they consider inadequate. And no, they wouldn't be satisfied with increased funding of public institutions—they see that as throwing good money after bad.

"I didn't just remove my daughter from a building in a school. I removed her from the consciousness that was there that was creating the symptoms of what I was seeing with her in her learning," Chantel Jones-Bigby, one of the Dallas moms, told the Texas Tribune. "Even if [schools] have more money, if you still have the same culture and consciousness, but new technology, what does that change?"

Funding Students, Not Schools

The usual approach for linking funding to students rather than buildings comes in the form of vouchers, which pay all or part of private school tuition. But flexible education approaches require equally flexible support, which is increasingly provided by Education Savings Accounts (ESA). Adopted so far by 13 states, ESAs put per-student education funding in an account to be drawn down by parents for tuition, homeschooling materials, and other related expenses. In Arizona, ESAs provide 90 percent of the money that would have been spent on each student in public school to be used by families for other approaches. As of this month, over 70,000 students in the state are taking advantage of the program. The Dallas parents want the same opportunity.

"Education savings accounts would allow families to exit the public education system and use taxpayer dollars to pay for alternative learning settings like a microschool," notes Dey. "The three mothers would welcome those funds to scale up and pay for instructional materials and a dedicated learning space."

Texas lawmakers are debating whether to add their state to the list of those offering ESAs. Opposition comes not just from Democrats allied with public school teachers unions, but also from rural Republicans who fear diverting resources from traditional district schools. But as the example of the Dallas (and Arizona) moms makes clear, attaching funds to students instead of schools is likely to create more education opportunities as supply increases to meet demand.

A 2022 report from Florida, which offers ESAs, found that "in 2021-22, 16.7 percent of students in Florida's 30 rural counties attended something other than a district school, whether a private school, charter school, or home education. That's up from 10.6 percent a decade prior." According to the report, the number of private schools in rural Florida almost doubled from 69 to 120 between 2001 and 2021.

Public Schools Can't Serve Everybody

Fueled by ESAs and vouchers, flexible approaches like microschools serve a wide variety of needs and preferences. That's important at a time when, as The Washington Post recently reported, the ranks of homeschoolers have swelled by 51 percent during a period of declining public school enrollment with participants who are "more racially and ideologically diverse" than in the past. The Dallas moms are part of a wide spectrum of families who aren't well-served by one-size-fits-some government-run institutions staffed by government-employed teachers using government-developed curricula.

"If there's been anything that's been highlighted in a postpandemic world, it's how necessary being attuned to the individual needs of the student is," the head of a New York City microschool told The Wall Street Journal.

"As much as I would love the public school system to work for my child, it doesn't," Jones-Bigby told the Texas Tribune. "Am I responsible to the system or am I responsible to my child?"

Millions of other American families have faced the same conflict and understandably chosen the needs of their children over sacrificing those needs to keep the system going. Lawmakers who want to help could best do so by getting out of the way of families' education choices.

The post Black Moms in Texas Want Vouchers for Microschools appeared first on Reason.com.