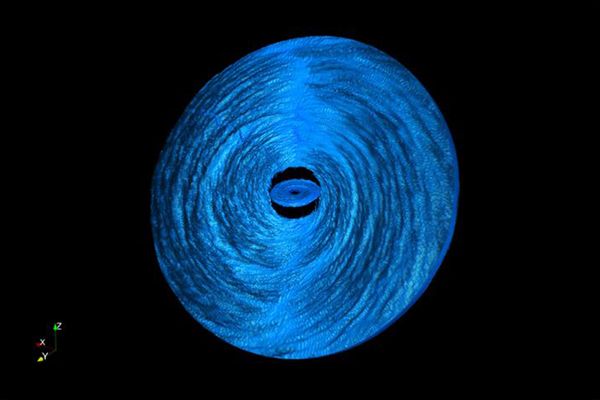

Across the universe, the immense gravitational pull of black holes sucks up whirlpools of gas called accretion disks. Due to something called the "Lense-Thirring effect," surrounding matter falling into black holes doesn't just fall straight down as an object dropped on Earth would. Instead, upon entering the black hole, objects start rotating in a process called "frame-dragging," which swirls surrounding plasma into spiraling accretion disks. A study published this week furthers what we know about what happens once that disk enters the black hole — and it's quite a violent process.

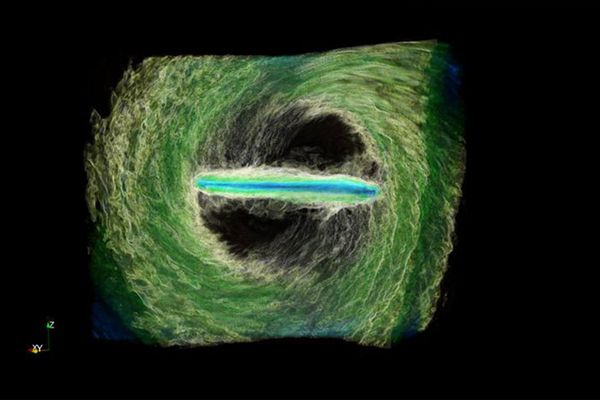

Using computer simulations, researchers saw that the rotations caused by the black hole actually warp the entire accretion disk such that its gas begins to cave in on itself and drive mass inwards faster. As it gets pulled in closer and closer to the belly of the black hole, the gravity gets so strong that the black hole eventually tears the accretion disk in two before devouring first the inner disc and then the outer one. Think of it like you'd tear a sandwich in half to be able to handle it more easily on its way to your mouth.

The study suggests black holes eat away at this accretion disk in a matter of mere months — rapid, on an interstellar time scale, and 10 to 100 times faster than prior research suggested, the authors reported in The Astrophysical Journal.

"This is a very violent process that definitely would look interesting observationally," said study author Nick Kaaz, a graduate student in astronomy at Northwestern University. "This is another one of those processes that can force the black hole to eat extremely quickly."

Astronomers have been working to understand accretion disks' behavior since the 1950s, with decades of research conducted to understand one of the most high-energy systems in the universe. Initial studies assumed that the angular momentum of the accretion disk would synchronize with the angular momentum of the black hole, Kaaz said. In the 1970s, scientists realized the two could actually be misaligned, but calculations at the time were limited to what could be done with pen and paper, and the full extent of how that misalignment affected the system wasn't well understood, he explained.

"In reality, things can be really severely misaligned, and in those extreme cases we have to resort to computer simulations," Kaaz told Salon in a phone interview. "It was only when computer simulations got advanced enough that we were able to look at this and say, 'We're missing something.'"

This study leveraged the power of one of the "smartest" supercomputers in the world, Summit, to calculate what happened when an accretion disk got dragged in by a black hole's gravity. Running at 200 petaflops, or 200,000 trillion calculations per second, Summit is about eight times faster than its predecessor supercomputer. Even with that computational power, the simulation took between three and four months to run, Kaaz said.

"This is basically at the limit of what scientists do," Kaaz said. "There are very few astrophysics simulations that are comparable on scale to what we looked at here."

The relationship between black holes and accretion disks is one of the most energy-consuming processes in the universe, right up there with gamma-ray bursts, in which black holes devour entire stars, Kaaz said. One mystery Kaaz is particularly interested in is "changing-look quasars," in which black holes feeding on gas at the center of galaxies experience alternating periods of luminosity and darkness.

Understanding how the black hole feeds on the gas in its accretion disk can provide clues into why the light that is emitted from the system changes over time. It could be the black hole consuming a portion of its accretion disc causes its light to dim in periods of changing-look quasar darkness.

"This supports the tantalizing hypothesis that some [changing-look quasars] may be the observational result of the tearing process," according to the study. "We plan to perform a dedicated comparison of [general-relativistic magnetohydrodynamic] disk tearing to [changing-look quasars] in an upcoming work."

.png?w=600)