Around 46 million people across the UK are expected to have visited their local high street to go shopping over the last weekend in November, encouraged by so-called Black Friday sales. The projected spend in-store and online is forecast to reach close to £9 billion.

How much of a saving there is to be made on Black Friday is debated. But even if they are a way to get a head start on your Christmas shopping – and important for retail businesses – by encouraging people to buy things they don’t necessarily need Black Friday sales can have a detrimental impact on the environment.

In 2022, research estimated that 400,000 tons of CO₂ would be released into the atmosphere due to transportation associated with Black Friday in the UK that year. When considering the waste from packaging and the fact that up to 80% of Black Friday purchases end up in landfill after only one use, the damaging consequences of these mass sales become clear.

Clothes are, unsurprisingly, among the most popular items purchased during this period. Fashion is already the world’s second most polluting industry, accounting for up to 8% of global carbon emissions. On Black Friday, the carbon footprint of clothing sales is reportedly 72% higher than on any other day.

These statistics show that we need to consume more sustainably. The practices employed by the Victorians to mend, sell and reuse old clothing might offer us some valuable lessons this Black Friday.

Mending, wearing again and buying second hand

For the Victorians, clothes were much more economically and emotionally valuable than they are today. Before the introduction of the sewing machine in 1851 and the rise of the ready-to-wear industry, clothes were made by hand, often at home.

A basic knowledge of fabrics and textiles was therefore commonplace, especially among women, who would have undertaken the majority of the household work. Making and repairing clothing were important practices that women devoted much of their time to, and sewing was a valuable domestic skill.

In contrast to today’s “throwaway culture”, where clothes are produced cheaply and quickly before being bought and disposed of after only a few uses, the Victorians carefully extended the life cycles of their garments. Employers even often handed lightly used articles of clothing down to members of their household staff.

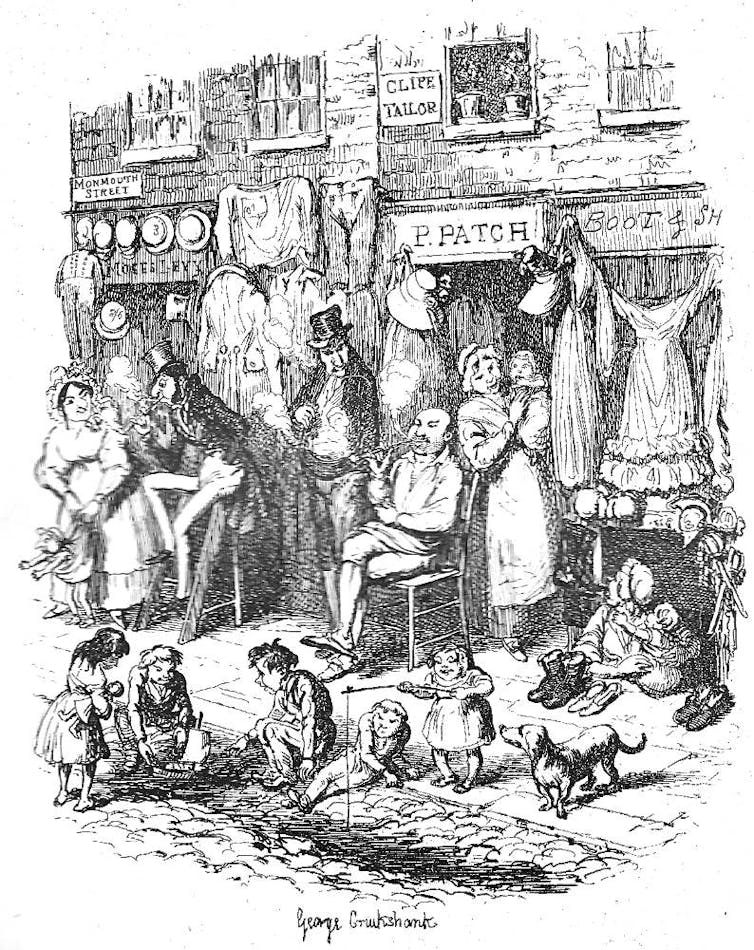

The trade in second-hand clothes also became increasingly widespread from the late 18th century. Except for the very wealthy, the majority of people living in the UK would have worn at least some second-hand clothing.

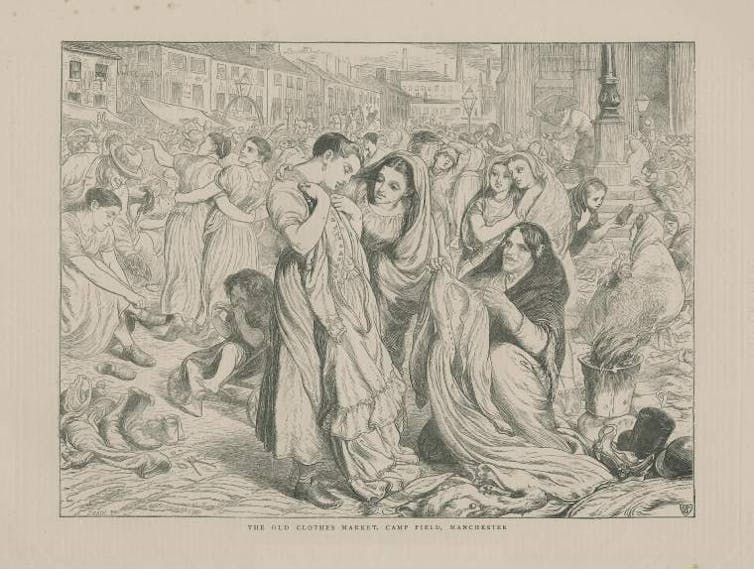

During this period, old clothes were routinely collected by itinerant hawkers whose job it was to exchange flowers, china or money for cast-off clothes. They would then deposit old clothes in second-hand markets in major cities, where they would be repaired and sold on again.

Recycling clothing

Even when clothes were seemingly beyond repair, they were rarely thrown away. In 1865, an article that was published in The Leisure Hour, a Victorian era magazine, explained that “old clothes, after they have served their purposes of two or three classes of society, are yet far from closing their career.”

Rags could be collected and taken to papermills to be recycled into paper, while woollen textile waste was ground in mills to produce “shoddy” – a type of recycled cloth.

Beyond that, rags were even used as manure for growing Hops, or as English poet and philosopher Edward Carpenter claimed in 1887, for growing his potatoes:

“When my coat has worn … and got weather-stained out in the fields with sun and rain — then, faithful, it does not part from me, but getting itself cut up into shreds and patches descends to form a hearthrug for my feet. …when worn through, it goes into the kennel and keeps my dog warm, and so after lapse of years, retiring to the manure-heaps and passing out on to the land, returns to me in the form of potatoes for my dinner.”

The Victorians were not always motivated by environmental concerns in quite the same way that we are today. Nevertheless, they were driven to care for their clothes for reasons of thrift, economy and to prevent waste.

The European Commission announced in 2020 that it aims to achieve a circular economy by 2050. The initiative includes a vision to minimise textile waste and increase the recycling of garments. To bring this vision to fruition, there could be valuable lessons gleaned from the Victorians and their approach to handling old clothing.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Danielle Mariann Dove does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.