Developers broke ground on a vacant lot Tuesday that would be the first of 11 newly constructed homes on a single block in West Woodlawn as part of an initiative that encourages a collective of Black developers to fill the void left by demolition crews years earlier.

Five developers — Sean Jones, DaJuan Robinson, Bonita Harrison, Keith Lindsey and Derrick Walker — acquired 11 vacant lots on 6300 block of South Evans Avenue from the Cook County Land Bank as part of an initiative dubbed Buy Back the Block.

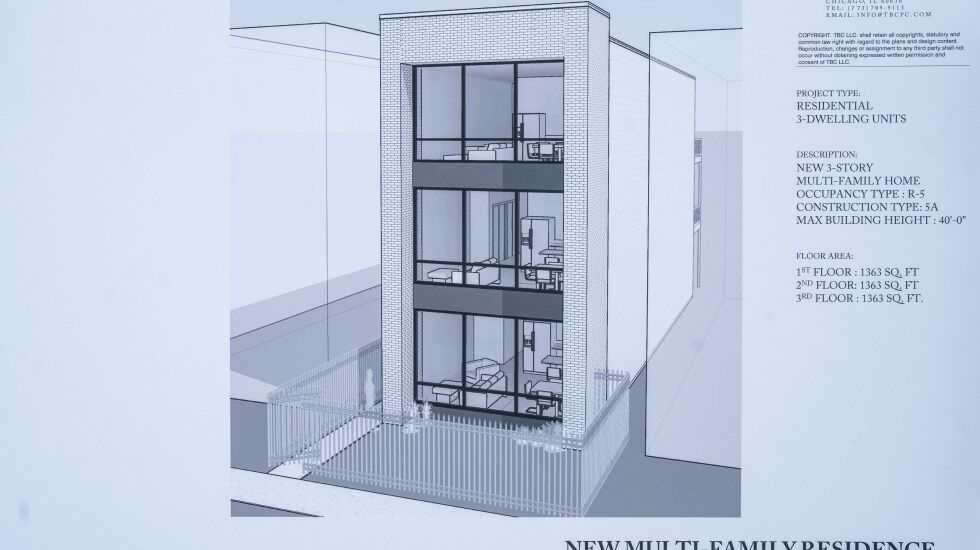

The plan is to build three-flats on each of the lots that will spur 33 new housing units in an area that is riddled with vacant lots. Each of the units will offer three bedrooms and two baths and will be known as West Woodlawn Pointe.

The all-Black team hopes to transform the block through the development, which is said to create more than 150 jobs with an “emphasis” on hiring locally. Each of the developers acquired the lots from the Cook County Land Bank for $1,000 per lot, according to public records.

Renderings of the new multifamily building indicate each floor will be over 1,300 square-feet and with large open windows.

The Cook County Land Bank Authority, an independent agency of the county, was founded in 2013 to help address communities hit hard by the mortgage crisis. Much of the services have focused on rehabbing vacant homes, but the Buy Back the Block initiative indicates a shift to new construction properties.

“I do hope this is a model that we will continue throughout Chicago,” said Eleanor Gorski, executive director of the Cook County Land Bank Authority. “It takes a special vision to look at a block full of vacant lots and see a thriving community like this development team did, but West Woodlawn Pointe will be bigger than just this block.”

Gorski said West Woodlawn Pointe is a “development by the community, for the community and with the community” and she hopes the model of Buy Back the Block can be replicated across the county to trigger economic growth in under-resourced communities.

Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle appeared at the ground-breaking to show her support, speaking candidly about how South and West Side neighborhoods have suffered from “racist disinvestment for generations” as predominantly white neighborhoods in Chicago have received the “lion share of investment.”

Preckwinkle said vacant lots across the city — concentrated overwhelmingly in Black communities — are a primary example of systemic failure and racist policies.

“Failure to prioritize our residents who have been most impacted by predatory lending and housing discrimination,” Preckwinkle said, — “That’s why programs like Buy Back the Block increase fair housing in Black communities and build Black wealth.”

Preckwinkle blamed the city for its longstanding policy of tearing down uninhabited homes for leaving thousands of vacant lots around Chicago today. She reflected on when she was an alderperson of the 4th Ward.

“The city’s policy for decades — didn’t start in 1991 when I became alderman — the city’s policy for decades was to tear down housing in Black and Brown neighborhoods,” Preckwinkle said. “It’s just incomprehensible.”

Preckwinkle said she was grateful for the Cook County Land Bank’s mission in helping boost homeownership in under-resourced communities to help reverse some of these impacts of some of these polices, but it was important for people in government to recognize the “profoundly racist, disturbing public policy” that has “destroyed so many of our neighborhoods.”

The Chicago Department of Housing in partnership with the Chicago Community Loan Fund has put up a $1.4 million commitment in loan loss reserves to help back the construction loans for the West Woodlawn Pointe development. The commitment is part of the Housing Department’s Neighborhood Rebuild program focusing on supporting local developers of color to help revitalize communities historically disinvested.

“Too often the story of places like Woodlawn are focused on what’s absent, the absence of amenities, the absence of investments, and it’s right to point out that neighborhoods like this didn’t get this way organically,” said Marisa Novara, the city’s housing commissioner. “We need to name that wealth was stripped from these communities.”

Novara said the commitment from these developers to build on these vacant lots is a story about what is working in Woodlawn rather than what it is lacking. Once completed, she said, there will be 11 new homeowners living in the 3-flat buildings with 22 rental units available just steps away from public transit.

“We are extremely excited about this development and what it means to the West Woodlawn community,” developer Sean Jones said.

.png?w=600)