Betty Bersinger was walking down Norton Avenue one morning in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Leimert Park, pushing her three-year-old daughter in her stroller, when she came across a gruesome sight.

At first she thought she had stumbled upon a discarded mannequin. But Bersinger had discovered the body of 22-year-old aspiring Hollywood actress Elizabeth Short, perfectly severed in two.

What was even more curious was that there was not a single drop of blood found at the scene.

It led the Los Angeles Police Department to believe that Short’s body had been moved from the spot where she was murdered 78 years ago this week on January 15, 1947, and deliberately left on the street.

Bersinger raced to contact the authorities.

The case of Short — nicknamed the Black Dahlia — has both horrified and gripped the nation, and the world, for decades. Short’s murder remains unsolved to this day and became the inspiration behind many books, films, and true crime series.

Who was Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia?

The case sparked a media frenzy when news broke and Short was dubbed “the Black Dahlia” by the press — partly inspired by the popular 1946 film noir The Blue Dahlia, and because the 22-year-old would often wear sheer black clothing and had striking black hair.

Born on July 29, 1924, Short was one of four sisters and grew up outside of Boston, according to the book The Black Dahlia: Shattered Dreams, written by Brenda Haugen. Short’s life was marred with family drama and health problems. Her father lost all of the family’s savings in 1929 after the stock market crashed and he suddenly disappeared. The family believed he took his own life after his car was found abandoned on Boston’s Charlestown Bridge.

Growing up, Short suffered from a respiratory condition and had to undergo surgery when she was 16. She spent the winters in Florida with family friends to escape the cold Massachusetts weather. And she had little education having dropped out of high school.

In 1942, Short’s mother received a bombshell letter from her husband, who they had presumed was dead. He had misled them and had a new life in California. Short temporarily went to live with him, but moved out in early 1943, according to Haugen’s book.

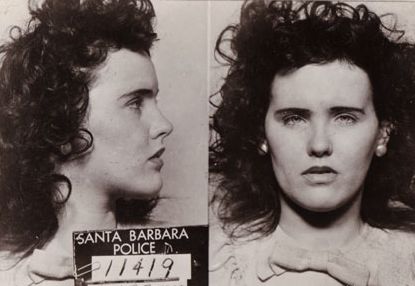

Her final years were unstable as Short moved from place to place. She relocated from her father’s house to Santa Barbara, where she was arrested for underage drinking and sent packing back to her mother’s. She then moved back to Florida briefly before moving to L.A. to make it as an actress.

The six months she lived in L.A., Short never seemed to be in one place for too long, working different jobs and moving between addresses. She had an active social life when it came to dating and men reportedly showered her with gifts. Police later discovered the names of 75 men in her alleged address book.

Former police officer Vince Carter said that Short’s life in Hollywood “seemed to follow a pattern,” he told Haugen for her book. “She didn’t have any visible signs of employment, she’d be broke, and then suddenly have some money,” he said.

“Her roommates, the bartenders, and the hotel clerks all came up with the same story. She was secretive — never one to confide,” Carter added.

Short remained in L.A. until her murder, apart from a brief stint where she fled to San Diego out of fear of an ex-boyfriend, according to the book Black Dahlia Avenger: A Genius Murder by Steve Hodel.

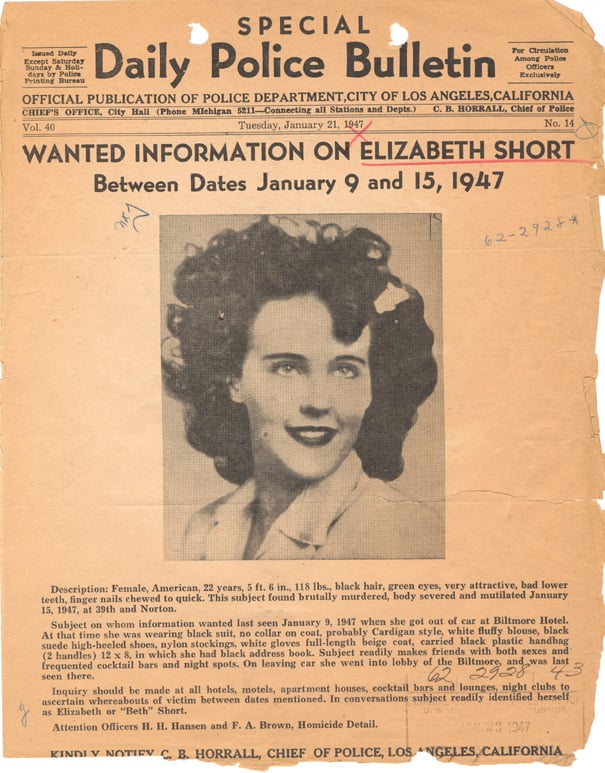

After this brief spell away, she returned to the city on January 8 with a traveling salesman she had been dating and was dropped at the Biltmore Hotel. She was reportedly “frightened.”

In the hotel lobby, Short was reportedly seen making several panicked phone calls that evening and left the hotel at around 10 p.m.

The whereabouts of her final days are contested, but that evening in the hotel lobby was the last confirmed sighting of her alive.

False confessions and a mysterious package

After Bersinger stumbled upon the grisly sight of Short’s mutilated body on January 15, authorities identified her via fingerprints which matched the set they had taken when she was arrested for underage drinking a few years before.

Their suspicions turned to medics because of the precision in which Short’s body had been cut.

“Based on early suspicions that the murderer may have had skills in dissection because the body was so cleanly cut, agents were also asked to check out a group of students at the University of Southern California Medical School,” the FBI’s historical account of the case says.

Police had several leads, but none ever led them to catch the killer. There was what many deemed to be a breakthrough on January 24, 1947 when a suspicious package containing Short’s alleged birth certificate, photographs, business cards, and an address book was mailed to The Los Angeles Examiner newspaper. Whoever mailed the package had used newspaper clippings to convey the message: “Here is Dahlia’s belongings.”

The package had been cleaned with gasoline — the same as Short’s body — and so police believed that they had their suspect. But the fingerprints were compromised and the lead went cold.

Police interviewed over 100 men in connection with the case, but still no one was charged. Several even falsely confessed to the crime.

But one former LAPD detective, Steve Hodel, remains convinced he has cracked the case. And the prime suspect? His own father.

Former LAPD detective who suspects his own father is the killer

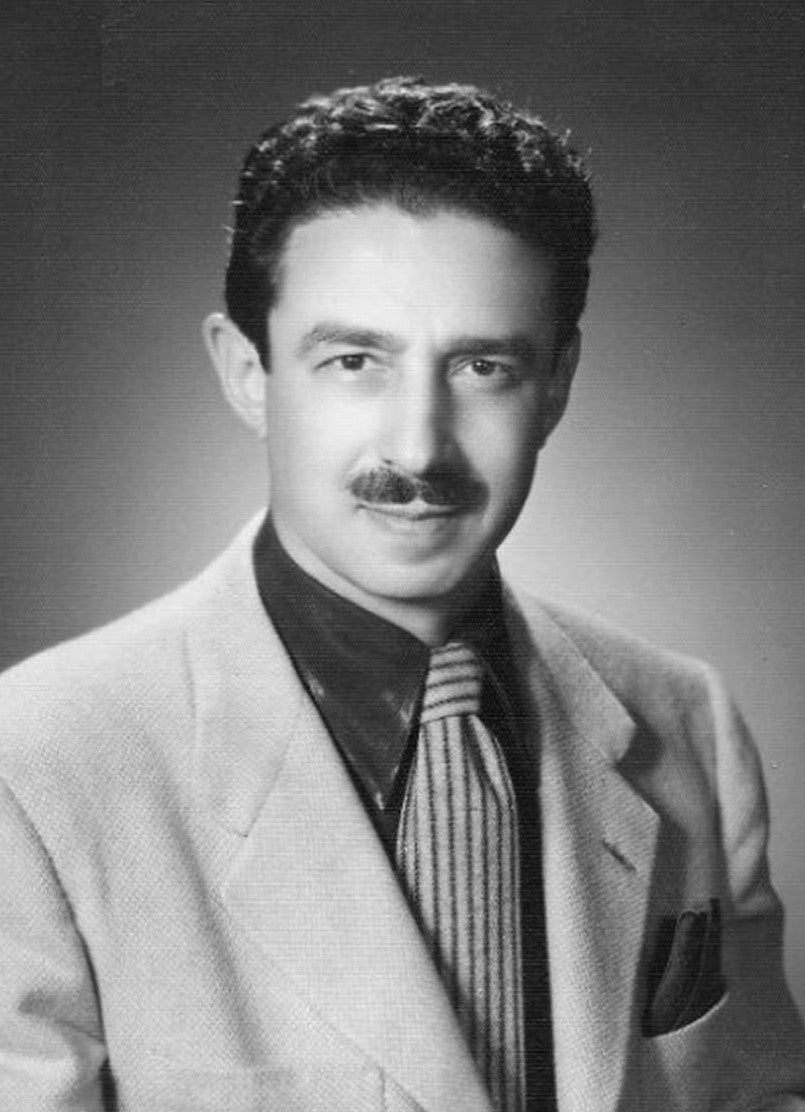

George Hodel was a gynecologist with his own clinic in L.A. who threw wild parties for Hollywood’s elite in the 1940s. His expertise fitted the theory that only a surgeon could have cut Short’s body with such precision.

Steve, whose 2003 book Black Dahlia Avenger: The True Story became a bestseller, became consumed by the case.

Hodel was rumored to have dated Short and he became a prime suspect after he was arrested in 1949 for allegedly sexually assaulting his teenage daughter. He was acquitted, but when the LAPD’s failure to solve Short’s case went before a grand jury later that year, Hodel was listed as a suspect.

His home was wire-tapped by authorities and in one chilling recording, Hodel appeared to confess to being involved in his former secretary’s death, and referred to the “Black Dahlia.”

“Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn’t prove it now,” Hodel was heard saying in the wiretap. “They can’t talk to my secretary anymore because she’s dead. Killed her. Maybe I did kill my secretary.”

Another tap revealed: “Realise there was nothing I could do, put a pillow over her head and cover her with a blanket. Get a taxi. They thought there was something fishy. Anyway, now they may have figured it out. Killed her.”

With the heat on him, Hodel left the city in 1950 and fled to the Philippines, where he remained for the next 40 years.

The wiretaps didn’t become public knowledge until 2003 when Steve shared what he had learnt about his father with the world after he died in 1999.

His evidence was compelling. Steve found five witnesses in newspapers that described Hodel as Short’s boyfriend around the time of her murder and he discovered receipts for bags of cement Hodel purchased days before the killing. Empty bags of cement of the same brand were found near Short’s body, which police believe her killer used to transport her to the street where her body was discovered.

A handwriting expert studied Hodel’s writing and compared it to the letters sent to the Examiner in 1947 – some of them were a match. And he discovered a photograph in his father’s belongings that bore a striking resemblance to Short, though it was never confirmed to be her. In his father’s possession Steve also found portraits by the surrealist artist Man Ray of a woman with dark, curly hair. He thought to himself, “My God, that looks like the Black Dahlia,” he told the Guardian.

More evidence materialized in 2018, when Steve claimed he had found a letter from a former police informant who said that Short was killed by a man with the initials “GH,” the South Pasadenan reported at the time.

Steve believed his father’s motive was jealousy – Short was reportedly involved with another man at the time – and also believed him to be a “sadist,” PEOPLE reported in 2003 when the book was released.

The LAPD looked into the evidence put forward by Steve, but never pursued it.

The former detective said he has given up on trying to convince officials to reopen the file.

“My judge and jury are the public,” he told the Guardian. “My readers. And they get it.”