WHOLE communities have been wiped off the map in the Upper Hunter as a result of the expansion of the region's mining boom and urbanisation.

Some that remain, like Bulga, only exist because defiant and determined residents fought tooth and nail to save the areas where generations of their families have lived.

Dozens of villages and hamlets scattered throughout the valley, including Ravensworth, Mount Thorley, Hebden, Long Point and Wambo, are now little more than names on a map.

While the region's coal addiction appears impossible to shake, the global push to meet climate change targets is forcing the pendulum to swing.

Experts warn that without intervention, the Upper Hunter's narrow economy is set to teeter, hingeing on the fortune of its major employer, the coal mining industry.

Economist calls for "immediate action"

Newcastle-based economist Bill Mitchell says crucial towns, such as Singleton and Muswellbrook, home to 40,000 people, could be left "ghost towns" if no action is taken as momentum for leaving coal in the ground accelerates globally.

In between, small hamlets and villages throughout the Upper Hunter will be caught up in the economic twilight zone, the precursor to more being wiped off the map.

Professor Mitchell, director of the Centre for Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE), says unless urgent action is taken by the state and federal governments to implement a structured transition plan to invest in new industries and support business and retrain workers, the Upper Hunter will be "doomed by coal".

Jobs will vanish, wages decline or disappear and businesses will be left counting the cost.

Everything from local cafes to real estate, health and education will be affected.

Worse still, young people and families will be forced to leave the areas where they have lived for generations.

He fears if government intervention is too little, too late, coal will become the latest calamity in Australian economic transitions - a disaster for thousands of Upper Hunter workers and businesses.

"There will be after the fact sweeteners and sugar hits, closing the gate when the horse has bolted type strategies," he says.

"Unless there is a major shift in the way the federal government thinks, then I think those towns are in for a bad future."

The only remedy for counteracting the coming woes is "immediate action" on a "structured plan", he says.

According to analysis by REMPLAN Economy, mining contributes more than 73 per cent, or $11.1 billion, of Singleton's economic output and employs 6626 people, representing 40 per cent of the town's jobs.

The industry contributes $960 million a year in wages and salaries, accounting for about half of the money in workers' pockets.

A 40-minute drive up the New England Highway, the picture is similar.

Mining accounts for $5.2 billion, or 60 per cent, of Muswellbrook's economic output.

It's also the largest employer accounting for more than 30 per cent, or 3120, of the town's jobs.

The data also reveals that the two Upper Hunter towns account for about 20 per cent of the Hunter Region's economic output.

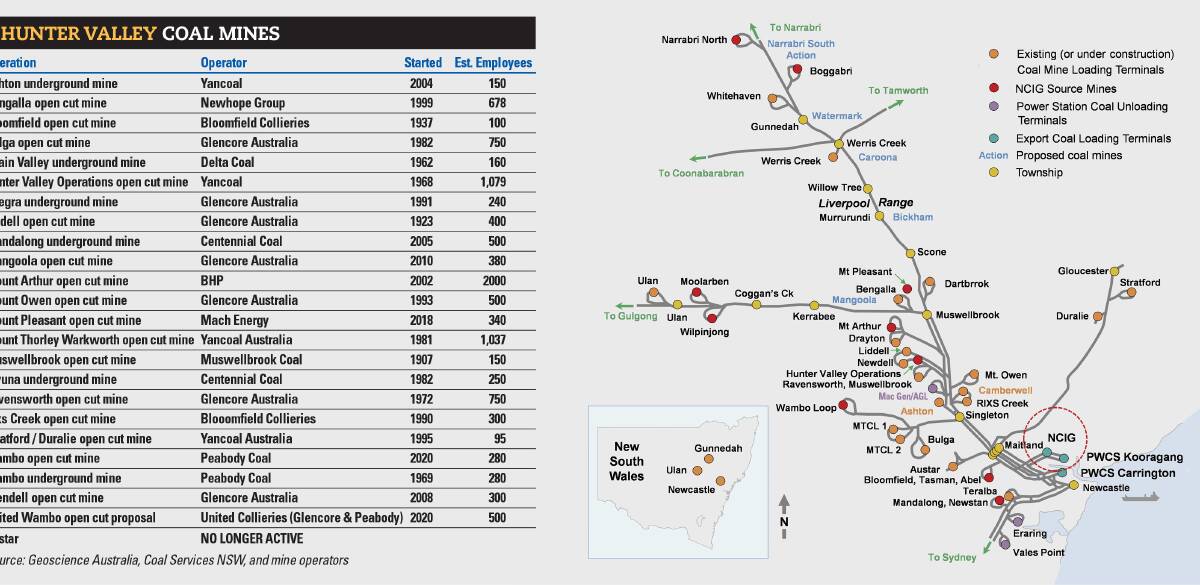

The NSW Minerals Council's latest annual member survey issued last week found the region's 28 mines supported more than 13,250 jobs last financial year, a slight increase on the previous year and the third highest result in the report's ten-year history.

Mining companies directly injected $6.1 billion into the Hunter economy, down just slightly on the previous year and the equal second highest result reported in a decade.

This includes more than $1.53 billion in wages and salaries, as well as almost $4.5 billion for goods and services purchased from 3160 Hunter businesses.

Minerals Council chief executive Stephen Galilee says the "very strong" expenditure highlights the importance of mining to the Hunter's economy, especially the Upper Hunter.

"These results also demonstrate how mining was able to provide economic strength and stability to the Hunter at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic," he says.

Coal mining reliance weighs heavy

Singleton and Muswellbrook chamber of commerce presidents, Sue Gilroy and Mike Kelly, agree that without mining the Upper Hunter would be on its knees.

They estimate up to 90 per cent of the towns' businesses rely on mining.

Mr Kelly, managing director of Wear Parts Services which supplies mines in the Upper Hunter and Western Australia, says mining is Muswellbrook's lifeblood.

He points to the recent spike in coal prices, strong export demand and lack of alternate energy source to fill coal's void as proof the industry isn't going anywhere soon.

Muswellbrook's Mount Arthur open-cut coal mine generated more than $1.4 billion in revenue for the six months to December 31 as owner BHP benefited from "all-time high" coal prices and "very strong demand" for power station coal.

Newcastle coal soared to a record price of $367 a tonne in late January, more than five times the $70 a tonne the same product was bringing when the market bottomed in mid-2020.

The main driver of the price surge is a global shortage, brought on by climate-change reluctance to approve new mines or extend the approvals of existing operations, exacerbated by production shortages as mines in NSW juggle their workforces around COVID-19 outbreaks and isolations.

Mr Kelly says if the coal industry died abruptly, Muswellbrook - the town that many see as the Upper Hunter's most vulnerable - would lose three-quarters of its population and the majority of businesses would close.

"At the moment if things go south for the mining industry we are in very big trouble," he says.

"The reality is though that there has been an influx of people into the Upper Hunter due to the pandemic, we have a shortage of rentals, property prices are going up and we're running at 3 per cent unemployment."

The "them and us attitude" when it comes to talking about coal mining and transition in the Upper Hunter isn't helping the debate, he says.

Rather, it should be a collaborative approach across all business sectors, government and the community to form a pathway forward.

In his view, the Australian export thermal coal industry has a long and healthy future.

"There are 16,000 people in Muswellbrook, if you get rid of mining and power generation, it would come back to about 4000 people. That is the reality," he says.

"The whole debate is wrongly phrased, we should be talking about a transition with mining.

"There is just no way we can throw out a labour intensive export industry when we don't have something to replace it."

Confronted with the choice between adapting or slowly dying off, Ms Gilroy says the Upper Hunter has great potential to reinvent itself.

She wants the region to become a case study of how mining towns can respond to a shifting economic landscape.

The way forward without coal

Investment in renewables, a shift back towards agriculture, including vineyards, boosting the equine industry and investing in emerging industries including tourism, are all possible avenues.

The time, however, is now.

"If we're being real, people know coal will eventually not be there and it does scare them," she says.

"People want their kids to grow up here and they want to know what that is going to look like. We have no plan, and we need a plan."

Hunter Jobs Alliance, a coalition of unions and environmentalists, was launched last year to help plan a post-coal future for the state's mining communities.

Its aim is to get past what is described as the "failed" jobs versus environment "dynamic".

The alliance has been calling for a new "Hunter Valley Authority", modelled on Victoria's Latrobe Valley Authority and on work done in the Western Australian power station town of Collie, south of Perth.

Coordinator Warrick Jordan says the Hunter has a lot of capacity and ability to adapt, but lacks coordination.

He says there are a lot of reasons to be optimistic and confident about meeting the coming challenge, and the coal industry will be around for some time to come.

But taking a "she'll be right" attitude will not serve the Hunter as many other regions around Australia are vying for "a slice of the action" when it comes to attracting new industries and creating jobs.

"We don't need to be thinking the sky is falling in, but we're not as coherent as we should be," he says. "There is a big absence as far as the Commonwealth having policy specific to the Hunter region. There is just a big blank space, actual policy is what we are missing."

The Hunter gets attention at "moments of crisis" or "political opportunity", but there is not a consistent approach.

"I have to give the State Government its dues, the initiatives they are planning, there is a more coherent suite of policy in critical areas," he says. "But we still need a well resourced local entity to do the practical things."

The Upper Hunter has had precious little traction attracting new industries outside of mining, which Professor Mitchell says is no surprise.

He says many regional centres around Australia are built around one major employer and if they leave or downsize it constricts consumption, shrinks businesses and forces workers into greater competition for an even smaller number of jobs.

"It's kind of inevitable, you can't really have a diverse labour market in a regional city like Singleton," he says.

"But what you can do, is in the proximate cities, the bigger cities like Newcastle or Maitland, you can make them attractors and provide skilled work opportunities and a more diverse labour market for those slightly further out regional cities to feed off."

An example of this would be the NSW government relocating one of its major departments like education, to a hub between Newcastle and Maitland.

Professor Mitchell says this would take pressure off Sydney and the whole Hunter region, including the Upper Hunter, would benefit.

Workers and wages

The average full-time total earnings in mining was $144,000 last year, meaning many workers would face a step down in pay in other industries.

About 48 per cent of Hunter coal workers are aged under 40 and 24 per cent are over 50.

Professor John Quiggin, of the School of Economics at Queensland University, says many people employed in Australian coal mining in February 2020 were not actual miners and had transferable skills.

About 14 per cent worked in white collar or managerial, professional and clerical jobs, while a large portion of the others, such as carpenters, truck drivers and labourers, worked in trades not tied to mining.

The exception is the category known as drillers, miners and shot firers, which accounted for about 20 per cent of total mining employment. Professor Quiggin says while wages are high in mining, conditions are often poor.

"An indication that the wages earned by workers in the mining industry represent compensation for poor conditions can be derived from evidence on workforce turnover," he says.

"The mining industry is characterised by annual turnover of 20 and 30 per cent, substantially higher than that for the labour market as a whole."

No one knows how many jobs will go. But coal mines and coal-fired power stations employ about 15,000 direct workers in the Hunter.

Throughout the Upper Hunter, climate action has long been a political battleground but increasingly even hardened sceptics acknowledge the looming economic transition.

It's the Federal Government's political resistance to the global shift that many see as confounding. Even the Hunter's biggest miner Glencore has responded to the move.

"Our strategy of responsibly depleting our coal portfolio over time reflects our belief that we remain the best steward for these assets and that coal will be required to support meeting global energy needs in the short term," it's 2021 Pathway to Net Zero progress report says.

Pro Capita economist and senior fellow Shirley Jackson says governments' response will determine the shape of the Upper Hunter's economic future in the years ahead.

He says research shows that when fossil fuel work dries up about a third of all workers go onto similar jobs, a third find work but take a dip in pay or job security and a third retire and never work again.

Without a coordinated intervention the cost will be borne by regions like the Upper Hunter and it should not be left up to state governments to go it alone....

Mr Jackson says it won't be climate change's python squeeze that will put the Upper Hunter on its knees, rather an inadequate response from governments in the face of the global shift away from coal will be a wrecking ball.

"Coal workers deserve a much better deal than that," he says.

"Transition cannot happen quickly, it has to come well before closure is coming. The time to start was about ten years ago, but we can only change the future, we can't change the past. The Federal Government is perfectly placed to roll out strong transition plans to support these communities."

For a transition to really be just, he says it must be coordinated and involve the local communities. That means consultation and, usually, early retirement packages for older workers as well as retraining and job-matching support for younger ones.

NSW royalty rich

The jobs piece is important, but the amount of money that is made out of coal poses a royalties question for government, Professor Roberta Ryan, a political sociologist at the University of Newcastle, points out.

"Linked to all of this, when we talk about the number of jobs, it pales into insignificance when you talk about the value of the coal sector in terms of productivity and in terms of royalties. That is pretty compelling ... how much money the coal sector contributes to royalties."

In 2019-2020, coal mining royalties raised $1.5 billion for the NSW State Government - the Hunter's coal kicking in nearly $727 million.

A portion of that is now being set aside in the Royalties for Rejuvenation fund to ensure the sustainable future of coal mining communities.

The fund, launched in April 2021, will inject $25 million per year into ensuring "coal mining communities have the support they need to develop other industries in the long-term".

The then Deputy Premier, John Barilaro, said the government understands that mines have "a lifespan", and NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet acknowledged that coal mining communities need "certainty".

"Hundreds of millions of dollars will be invested in these communities over coming years to ensure jobs and investment in our vital regional areas," Mr Perrottet said. "We want to ensure mining towns continue to have highly skilled well-paid jobs in growth industries that will lock in their economic security long into the future, so young people have the opportunity to remain in the town where they grew up," he said.

CFMEU Mining and Energy division district president Peter Jordan has described the Royalties for Rejuvenation program as "little more than spare change".

An eight-person panel representing "the interests of the local community, local business, unions, Joint Organisations of Council, industry peak bodies and advocacy groups across the Hunter region" will guide the fund's expenditure, NSW Deputy Premier Paul Toole's office says. That includes, controversially, the NSW Minerals Council's James Barben.

Royalties also trickle into the State government's Resources for Regions program which, since 2012, has seen $420 million allocated to 242 projects.

That includes 101 projects in the Hunter, worth $181,447,678, ranging from new bike paths, park upgrades, road upgrades and community facilities - spread across local government areas including Lake Macquarie and Newcastle.

That is a tiny fraction of the cash the region has generated - little more than two per cent of the $8.7 billion in royalties Hunter Valley coal has contributed since 2012.

If all of the 21 coal mine projects currently in the state government's approvals process pipeline - made up of expansions, modifications and extensions - were to get the go-ahead, they would generate an additional $2.2 billion in royalties.

Royalties are not, however, on an indefinite upwards trajectory. Calculations based on data provided by the Regional Department of NSW reveal that in the ten years to 2021, Hunter Valley coal royalties have dropped by 12.8 per cent.

The latest NSW intergenerational report, issued in June, forecasts that coal mining royalties in NSW are expected to more than halve by 2061.

Those figures send perhaps the most powerful kind of message to governments yet about the need to carefully plan the way forward.