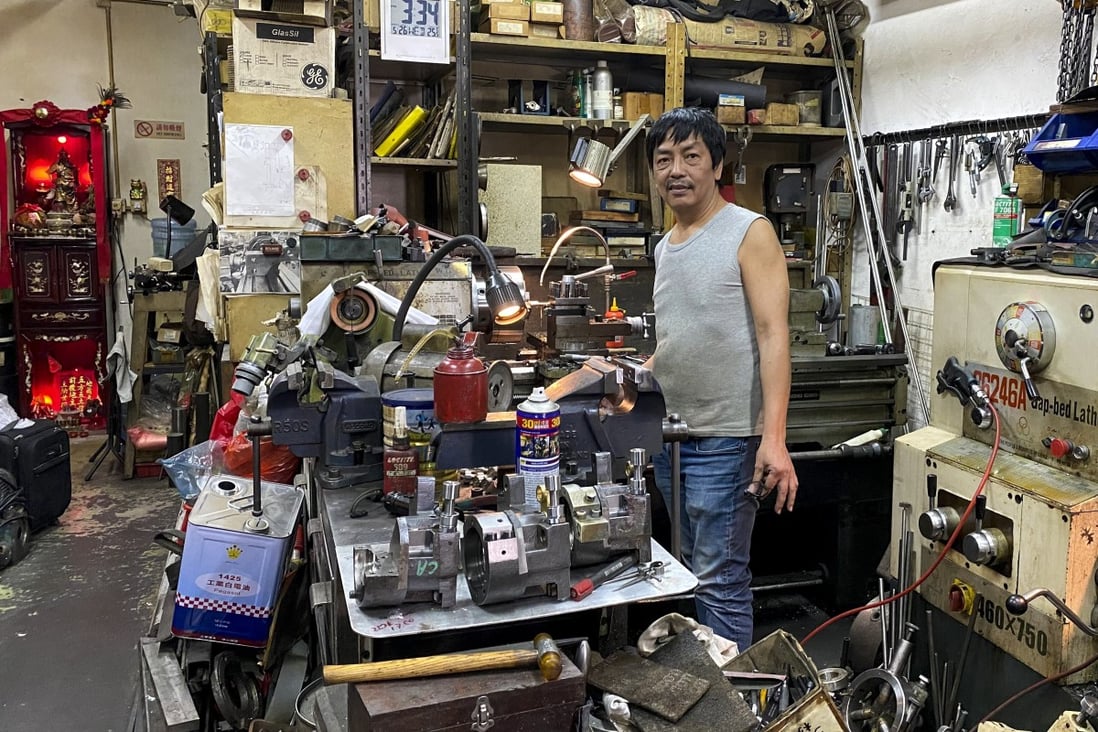

Lewis Wong Kam-lang has been repairing industrial printers, machines and electrical appliances at his workshop at the Wang Cheong Factory Estate in Cheung Sha Wan for more than 10 years.

“Workshops like mine are the emergency room for machines. We make quick fixes so companies can quickly get them up and running again,” said the 61-year-old owner of Hang Lee Machinery.

Now he has 18 months to move out, as the factory estate is making way for public housing.

He has to find a new place and dreads the “big headache” of moving his six large pieces of equipment, weighing about 15 tonnes in total.

“I’m worried I’ll be kicked out again in a few years and end up throwing money into the water. I just want stability so I can keep making a living,” he said.

Wong is among the tenants of four factory estates told to move out by the Housing Authority.

The 2,088 affected businesses must find new premises mainly in private industrial buildings, or compete for only about 60 vacant units in the two remaining factory estates run by the Housing Authority.

The authority announced on Monday that 4,200 public flats would be built by 2031 in the area now occupied by three factory estates, Yip On in Kowloon Bay, Sui Fai in Fo Tan, and Wang Cheong.

The proposal to take back factory estates for housing was in a raft of measures announced by Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor in her 2019 policy address, at the height of social unrest in the city. She noted that the lack of affordable housing was a source of public unhappiness.

The four factory estates earmarked for housing were built by the Housing Authority in the 1970s and 1980s. Its two remaining factory estates, in Kwai Chung and Tuen Mun, are not considered suitable for housing.

Hong Kong factory sites to provide 4,200 public flats to ease housing crunch

The compensation for affected tenants includes a payment equivalent to 15 months’ rent. Those who move out within nine months and do not bid for vacant units in the two remaining estates will get an additional HK$100,000 (US$12,820).

‘Livelihoods hit for so few flats’

Flora Mok Lai-chun, 69, manager of Honor Hardware and Industrial Materials, is worried she will not be able to find a suitable new location in the time she has to move out of her two units, each about 540 sq ft, at Wang Cheong Factory Estate. She sources construction materials for her clients, who have included dozens of government departments and the Ocean Park theme park.

Carrie Lam dismisses CY Leung’s land demands, hails own long-term vision

“It’s so unfortunate that the government is sacrificing our livelihoods to build so few flats. They are not only taking away our rice bowls, but also affecting our staff and their families,” said Mok, who has seven employees.

She hopes to find a ground floor unit to stay in business but if the rent is too high, she may close down.

The tenants worry that operating in private industrial buildings will mean higher rents and price fluctuations, unlike the security of three-year renewable leases on fixed terms offered by the Housing Authority.

Leung Kwok-hung, 71, owner of Sing Hung Printer Factory, has decided to retire after 21 years at the Yip On Factory Estate in Kowloon Bay.

He said he would have continued working if he was not forced to leave.

“I’m in my 70s and I have no problem working more than 12 hours a day. But there are so few areas left for workshops like ours, there’s nowhere to go,” he said.

Questioning the government’s decision to demolish the factory estates, he said the authorities would do better by building public flats on the fringes of protected country parks.

“We do all the small jobs that big factories won’t do. There will be no way back when all of these workshops are gone,” he said.

His neighbour, a tenant surnamed Siu, also in his 70s, recycles metal tools by sharpening blunt chisels.

“The coal is so hot and dirty. Young people won‘t do these jobs,” he said, adding he would also retire after moving out.

Major Hong Kong developer willing to release land for public housing

‘Eighteen months’ notice is ample’

In a reply to the Post, the Housing Authority said it was not legally bound to pay compensation when it terminated tenancies with due notice, but it had followed past practices to provide affected tenants help with relocation.

For example, a tenant leasing a 269 sq ft unit at a rent of HK$2,500 a month stands to receive HK$162,900 if the individual moves out within nine months and does not bid for vacant units in the two remaining factory estates.

Serena Lau Sze-wan, chairman of the authority’s commercial properties committee, said members of the committee had the affected tenants’ interests in mind when they approved a clearance package for them last week.

“We hope to help them as much as possible but we also cannot give too much because these funds are coming from the public coffers,” she said.

She added that with 18 months’ notice, the tenants had ample time to make plans, pointing out available locations they could consider.

According to the Rating and Valuation Department, there are 1.04 million square metres of vacant factory space in the private sector, with over half in Kwun Tong, Kwai Tsing and Tsuen Wan districts.

Factory owner To Wai-pan, 59, said: “We’re not opposed to moving out, and I support building more public housing, but the government must also strike a balance and help support the manufacturing sector, which played a huge role in Hong Kong’s economic development.”

His Sum Hing Kee Bamboo Steamer Company in Wang Cheong Factory Estate is one of the few places in Hong Kong hand-crafting steamers for dim sum restaurants.

The family-run business supplies about 300 restaurants, mostly in Hong Kong. Although the steamers are now made on the mainland, he still repairs them by hand at his workshop.

To said he had fond memories of Wang Cheong after spending 26 years there and becoming close friends with many other tenants. He added that he hoped to continue running the business somewhere else.

“It is very irresponsible of the authorities to demolish the factory estates in such a difficult period, when businesses have been hit by months of social unrest and the Covid-19 pandemic,” he said.