The federal government has been under significant pressure all week as it works to finalise proposed regulation to restrict gambling advertising. Currently, a partial ban is on the table.

This has led to severe criticism from gambling harm researchers, community organisations and some MPs and senators. A partial ban is inconsistent with the recommendations of a recent parliamentary inquiry, which unanimously recommended the need for a total ban.

Gambling is a demonstrably big problem. Australians are the world’s biggest per capita gamblers, losing about $25 billion a year. Nearly half of gamblers are at risk of, or already experience, harms from it. These include financial hardship, relationship breakdown, domestic violence, poor work productivity, criminality, insomnia, depression and suicide.

Why, then, is the government so reluctant to ban gambling advertising entirely? Part of the answer is in the industry’s strategic stakeholder marketing strategies, both publicly and behind closed doors. And they’re strategies we’ve seen before.

Mounting harms

Clever marketing, weak regulation, and technologies such as sports betting apps and online casinos are increasing opportunities to gamble.

In our research, gamblers’ stories of harm are extremely troubling:

The feeling of losing […] I hate even talking about it […] it makes me so upset […] It drives you crazy […] I’ve dropped my phone, smashed the screen […] because I was so upset […] I was out of my mind, it’s horrible.“

The social costs associated with these gambling harms in Australia are estimated to cost more than $10.7 billion each year. The problem is so significant that even banks are taking actions to address gambling harm to their customers.

But the gambling industry is putting up a good fight. The peak body, Responsible Wagering Australia, has denied advertising normalises gambling to children, and warned any bans would send people to illegal offshore operators. There’s evidence contradicting both these points.

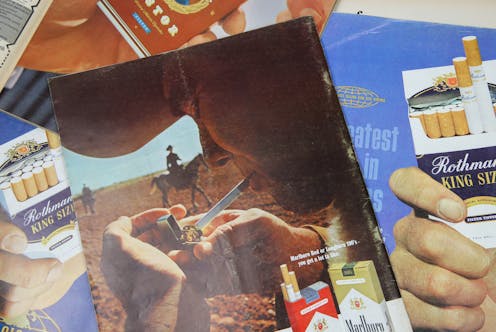

It’s part of a broader strategy to prevent further regulation. The tactics at play are very similar to those used by two other industries linked to health and social harms: alcohol and tobacco.

Strategic deja vu

These industries have used the full power of strategic marketing, not just to develop, promote, advertise and endorse their products, but also to influence government.

They do this through tactics such as extensive lobbying, media and public relations and stakeholder marketing. Tobacco companies have been known to funding favourable research or to challenge the findings of studies that have linked their marketing to consumption behaviours and harms.

Spruiking fears of job losses in hospitality, corporate social responsibility efforts such as funding community projects and setting up foundations are other strategic marketing examples used by these industries.

In the case of tobacco, this helped delay legislation banning advertising, introducing plain packaging and prohibiting smoking in public places for many years.

For alcohol, the industry has successfully avoided tighter restrictions on their marketing, despite clear evidence it helps drive harmful consumption.

What is ‘big gambling’ doing?

The gambling industry has learned from and adapted this playbook. Alongside the more visible media advertising, celebrity endorsements, sponsorship activities and a range of other tactics are used.

These include political donations (in the millions of dollars over the past 20 years), hiring lobby firms and even hosting lavish birthday lunches for our politicians.

Similar to big alcohol and tobacco, the gambling industry also funds research. It distorts and contests the findings of studies that link their marketing to health and social harms.

And as we see currently with the debate about what impact a ban on gambling advertising will have on free-to-air media, the alcohol and tobacco industries and media companies aligned their interests to protect revenue.

Read more: Does free-to-air TV really need gambling ads to survive?

As with the tobacco and alcohol industries before them, this strategic marketing playbook gives the gambling industry in Australia power, access and influence over policymakers. This may help explain why the current federal government seems resistant to a total ban on gambling advertising.

In the case of tobacco, strong regulations were required through the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control to restrict marketing and limit the use of these sorts of tactics. Crucially, these tobacco control efforts have been successful in reducing smoking prevalence, improving health outcomes and reducing harm. A similar framework has also been proposed for alcohol.

These rules are best practice recommendations to improve public health, including bans on advertising, reducing availability and use of price controls.

If we wish to effectively reduce gambling harm in Australia, similar robust regulations may be necessary. Such rules could include limits and declarations on political donations, banning gifts to politicians, tighter rules on lobbying and transparency about meetings with government, whether by the gambling industry or others. These efforts could then work alongside advertising bans currently being discussed, limits on sponsorship and controls on product development and availability.

We need an holistic approach to regulation that addresses the gambling industry’s clever use of strategic marketing. This would more effectively protect the Australian public and prevent gambling harm.

Ross Gordon has received funding from the Australian Research Council, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, and Suncorp Bank to conduct research on gambling marketing, consumption and harm. He has also received funding from the UK Medical Research Council, the European Commission, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Alcohol Education and Research Council, and Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education to research alcohol marketing, consumption and harm. Ross has served on the World Health Organization Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural Insights and Sciences for Health since 2020.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.