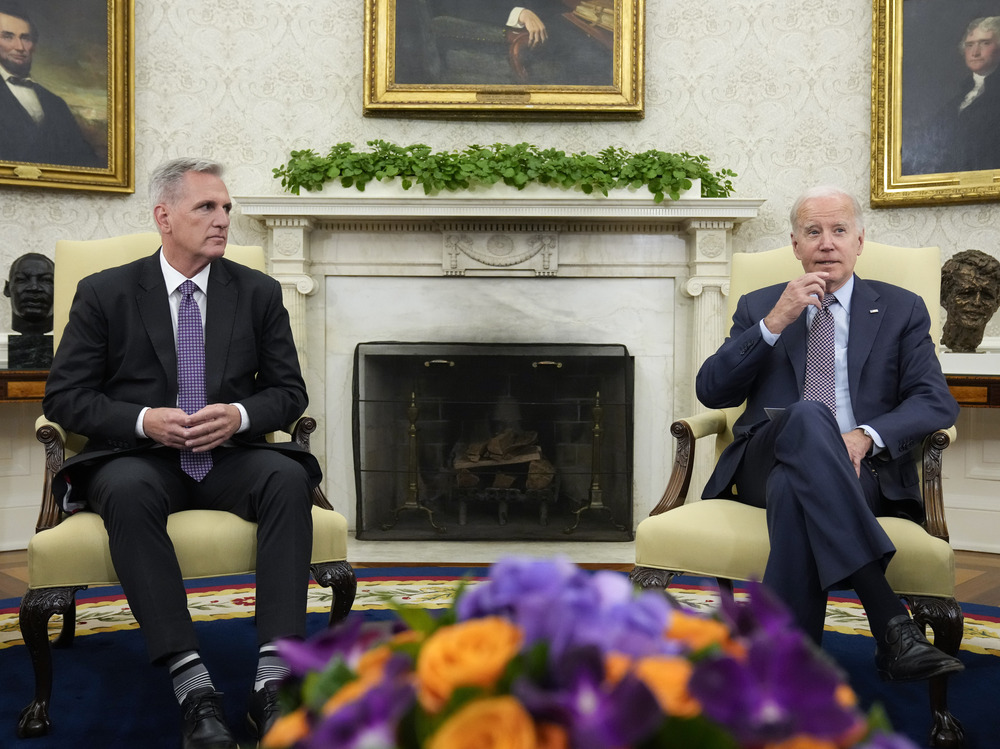

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and President Biden met at the White House to continue talks about the debt limit, and though it ended with no deal, they expressed optimism Monday they can strike an agreement and avoid an unprecedented default.

When asked about whether a deal can get through Congress by a June 1 deadline, McCarthy told reporters after the Monday meeting: "I believe we can get it done." Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen reiterated Monday that the nation could run out of money to pay its bills as early as that date.

Biden said that at the "productive" meeting he and McCarthy "reiterated once again that default is off the table and the only way to move forward is in good faith toward a bipartisan agreement." He noted that while there are areas of disagreement, the pair, their lead negotiators and their staffs "will continue to discuss the path forward."

Given that Republicans hold a narrow margin in the House while Democrats hold a narrow margin in the Senate, Biden also said Monday that he and McCarthy would need to reach a deal that was acceptable to both parties. "We got to get something can sell both sides," he said.

The face-to-face meeting follows a series of stops and starts to talks between designated negotiators for the two leaders since Friday — all while Biden was attending the G-7 summit in Japan. The president cut the second half of the trip short so he could be back in Washington, D.C., for continued negotiations with congressional leaders.

The Biden administration and House Republicans have each doubled down on their own red lines while simultaneously blaming the other side for stymied progress and stressing the need to avoid defaulting on the nation's debt.

McCarthy has repeatedly said that including work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents enrolled in federal safety net programs like food stamps is a must-have for his conference. That provision is included in a bill House Republicans passed last month that addresses raising the debt limit.

Progressive Democratic lawmakers were concerned when Biden suggested last week there was a possibility he would consider that proposal.

"I'm not going to accept any work requirements that go much beyond what is already — what I — I voted years ago for the work requirements that exist," he said. "But it's possible there could be a few others, but not anything of any consequence."

There have been signals that there are general areas where both parties would compromise on a potential deal — including $60 billion in unspent COVID-19 relief money and permitting reform — which would make both oil and gas projects as well as green energy projects happen more expeditiously.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has repeatedly warned lawmakers that the clock is ticking — the U.S. could run out of money to pay its bills as early as June 1. That puts a major crunch time on both chambers of Congress. McCarthy has said that the House would need 72 hours before it would vote on any bill, before it heads to the Senate.

What a default could means for the U.S. economy

The U.S. has never defaulted on its debt before.

In 2011, during a similar standoff over raising the debt ceiling, the threat of a default alone sent markets into a freefall. Ratings agencies downgraded the U.S. from its top AAA credit rating to AA+ as a result of the debate.

Most economists agree an actual default could result in a recession. A default would severely affect financial markets, increase mortgage rates and interest rates on credit cards, could cause government workers and Social Security recipients to go unpaid, and could make it difficult for businesses and citizens to borrow money.

Treasurys, which are held by countries around the world and used as collateral in financial transactions, are viewed as some of the safest investments worldwide.

Yellen declined on Sunday to specifically state which bills would go unpaid.

"If the debt ceiling isn't raised, there will be hard choices to make about what bills go unpaid," she told NBC's Meet the Press.