New Delhi – Nearly three years after toxic gases from a Union Carbide Corporation’s (UCC) factory killed an estimated 15,000 people and left more than half a million seriously ill in the Indian city of Bhopal, a chemical trading firm – Visa Petrochemicals Private Limited – was incorporated in Mumbai.

Over the next 14 years, Visa Petrochemicals became a linchpin in an elaborate plan by American chemical giant UCC to discreetly sell its products in India while it evaded criminal trial for spewing lethal gases that killed the residents of Bhopal on the midnight of December 2, 1984. A Bhopal court had declared UCC’s then-CEO Warren Anderson a fugitive and ordered that the properties and products of UCC and its subsidiaries, all of which were proclaimed offenders and absconders in India for not appearing in the criminal trial against them, be seized.

Internal company records, accessed by The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) for Al Jazeera, now reveal that UCC discreetly sold its products to several firms owned by the federal and state governments, and some large private corporations. Among them was a buyer from ground zero: a firm owned by the government of Madhya Pradesh, the state whose capital Bhopal saw one of the world’s worst industrial disasters. The firm was a joint venture partner in a cable company that bought UCC products.

To create a discreet backdoor into India where the public saw it as the devil of Bhopal and courts were going after it, UCC and its associates floated three firms, one each in India, the United States and Singapore. In its internal records, Carbide employees called them “front” and “dummy” companies. At times, they referred to these companies as their “extended arms”. These firms took orders from Indian customers on UCC’s behalf, relabelled its products, routed them through multiple ports and supplied them to customers. The company sold materials that went into the making of household products ranging from telephone cables to paints.

UCC internally admitted that the dummy companies were “a legal requirement” to help it keep its “distance from India”. This admission was made in an internal business plan for UCC to keep selling its goods in India even after the Indian court had ordered the seizure of all its moveable and immovable assets in the country. The court did not explicitly declare the future sale of UCC products illegal. But it had ordered that all its assets be seized, including products and goods meant for sale.

The government companies that traded with UCC knew about this backdoor arrangement, as UCC privately informed them when its front company participated in tenders.

This backdoor arrangement continued until 2002, a year after American giant Dow Chemical bought all assets of Carbide for $9.3bn. The period saw Union governments led by both the main Indian parties, Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Between 1995 and 2000, the company sold more than 55,800 tonnes of wires and cables in the Indian market, according to records. In 1999 alone, the company sold products worth $24m through this arrangement.

While media in India had reported that Dow relabelled UCC’s products and sold them in the country through a front company for a year, the group’s elaborate discreet channels – the network of front and dummy companies – and information on UCC customers, including government corporations that knowingly bought products through this shadowy channel, had been buried so far. Information on the people behind the dummy companies and their workings – active for almost 14 years – is being published for the first time.

The fountainhead of these revelatory records are documents submitted in a US court hearing when Dow, UCC and its dummy companies got into litigation over the pricing of products in the early 2000s and submitted evidence of their relationships.

The collective sent detailed queries to UCC and Dow but did not receive a response.

Lethal business

It was the death of a technician from phosgene poisoning on a cold Christmas eve in 1981 that first foretold an impending catastrophe and revealed cracks in the UCC factory in Bhopal. UCC’s global profits had plummeted 90 percent in the three years preceding the disaster. Its India unit could sell less than half its production capacity of Sevin, a “miracle insecticide” born on the banks of the Hudson and reborn in India on the sands of Narmada.

Layoffs took hold, and cost-cutting affected safety and maintenance protocols in the Bhopal plant. On the night of the disaster, the safety valves and alarm systems of the tank that stored the lethal chemicals, including the lethal methyl isocyanate used in the production of Sevin, did not work. Some were dysfunctional, others were turned off since malfunctioning alarms would repeatedly go off in the leaky plant.

“I remember that night,” said 60-year-old Leelabai, who lives in Bhopal’s JP Nagar, located near the disaster site. At a distance, overlooking her one-room house is the metallic carcass of the factory.

“I remember it like yesterday. Our eyes burned, and people began vomiting. There was a stampede,” she said, tearing up. A deadly fog had filled nearby slums. Death struck in seconds, and no one was prepared.

Leelabai and her husband were the only survivors in the family. Her three children died over the years as their health debilitated. “Our lives are worse than death,” she said.

“None of us knew they had chemicals this dangerous,” Savitribai, another resident of JP Nagar, told TRC.

More than 2,000 people died over the following days after breathing a cocktail of deadly fumes, one being hydrocyanic acid, a chemical that causes a series of reactions leading to loss of blood flow to the brain and resulting in immediate death.

As per estimates by survivors’ groups, 13,000 people died over the next few years from damaged lungs, brains, kidneys, and nervous and immune systems. Hundreds were disabled for life. The poisonous chemicals polluted (PDF) Bhopal’s soil and water for decades, causing a perpetual health tragedy for residents.

Three days after the disaster, when Anderson – still one of the West’s most powerful industrial leaders – visited India, he was placed under house arrest in UCC’s luxury guesthouse over charges including culpable homicide, causing death by negligence. Three hours later, Anderson, whose factory poisoned a city, was released on a bail of 25,000 rupees (about $300 at the current exchange rate). Within 24 hours, he was mysteriously flown out of Bhopal in state Chief Minister Arjun Singh’s jet and then to the US in the company’s plane. Anderson never returned. He never faced trial. And died peacefully in 2014, aged 92, on US soil where he rose from a salesman in UCC to its CEO.

UCC was still the US’s third-largest chemical manufacturer and 37th among the top 50 US companies in 1984. The Bhopal accident was bad for business. It was a public relations nightmare and would run up several millions in legal costs. UCC had to find a way to continue trade. Who would help the company move past this?

The spin-off

For up to two years after the disaster, UCC did its business in India as usual despite protests and outrage from survivors and activists. In December 1987, India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) filed charges against Anderson, UCC and its subsidiary that oversaw Asia operations, Union Carbide Eastern, which was incorporated in Delaware, US. By then, UCC had set in motion a series of events that would help retain its grip on the Indian market while keeping a safe distance from courts. The first among them was the birth of Visa Petrochemical Limited.

The company was a “spin off from UCIL [Union Carbide India Limited]”, said Visa Petrochemical’s Annual Business Plans, submitted to the UCC in 1994. Ravi Muthukrishnan, the then India country manager of Dow Chemical, noted in an email to his bosses in 2001 that Visa Petrochemical was formed by former UCC employees engaged in “international trade” after the “government advised them to exit totally out of India”. He also noted that Visa, whose name was changed to MegaVisa Marketing and Solutions in 1999, was UCC’s “extended arm” into India.

UCC signed an agreement with Visa Petrochemical on 14 November 1987, 15 days before the CBI filed charges against the former, and designated the new company its “non-exclusive distributor in India”. The arrangement allowed UCC to route its products through Visa. Under the contract, Visa’s “duty” was to “canvas and promote sales” of UCC products. It was to do all this while “representing” UCC. The latter’s business could now proceed without the taint of its past.

In the next few years, UCC incorporated a new subsidiary – Carbide Asia Pacific – in Delaware, which slowly took over the operations of Carbide Eastern, an accused party in the Bhopal case. This ensured UCC’s Asia businesses, including the agreement with Visa Petrochemicals in India, were carried out by a firm not named in the case.

In 1989, UCC paid $470m as compensation for the disaster in response to the civil lawsuit, which the survivors’ representatives said was a meagre $500 for each victim, and one-sixth of the compensation initially claimed by the government. But the government accepted the proposal without consulting the victims.

In 1992, after all the foreign parties who were accused evaded Indian courts in the criminal lawsuit, Bhopal’s chief judicial magistrate seized all of UCC’s moveable and immovable properties in India. It did so after noting: “The accused Union Carbide USA wants to evade the prosecution going on in this court by transferring its properties in India by any means.” The magistrate labelled Anderson, UCC (parent company based in the US) and Union Carbide Eastern as “absconders”.

For UCC, continuing trade now would be tougher and more complicated than before. UCC and its affiliates had to come up with a new plan.

New partners

In February 1994, a young businessman called Ajay Mittal from Mumbai met UCC officials in Danbury to discuss the shipment of its products. The officials found the meeting with Mittal “excellent” and “frank”, as per a fax sent by UCC officials to Mittal a day after their meeting, a copy of which was submitted in court documents.

Mittal, an American business school graduate, is an heir to the realty business family Mittal Group and currently owns and runs Arshiya Limited, a logistics and supply chain firm. A 2001 Dow India internal report described his family as a “fairly established group” that owns more than 3,000 buildings in Mumbai.

After the court declared UCC an “absconder” and seized its India assets, Mittal’s businesses proved crucial in fulfilling Carbide’s “legal requirement to distance from India”, reveal company documents.

Mittal owned a firm in Houston, called Mega Global Services, which was set up in March 1993, documents show. A month later, Carbide Asia Pacific terminated its contract with Visa Petrochemicals and, on the same day, signed a new agreement with Mega Global.

Mega Global Services’ role, according to the new contract, was to first buy UCC products and resell them to “customers located in India”. UCC’s products would be relabelled as that of Mega Global Services in this process.

Mittal did not stop there. Two months after the meeting in Houston, he bought an 89.5 percent stake in Visa Petrochemical. His group now owned both the intermediaries crucial to UCC’s backdoor channel. Mittal, UCC and Visa Petrochemicals worked out Carbide products’ route into India, which was laid out in an annual business plan of Visa Petrochemical.

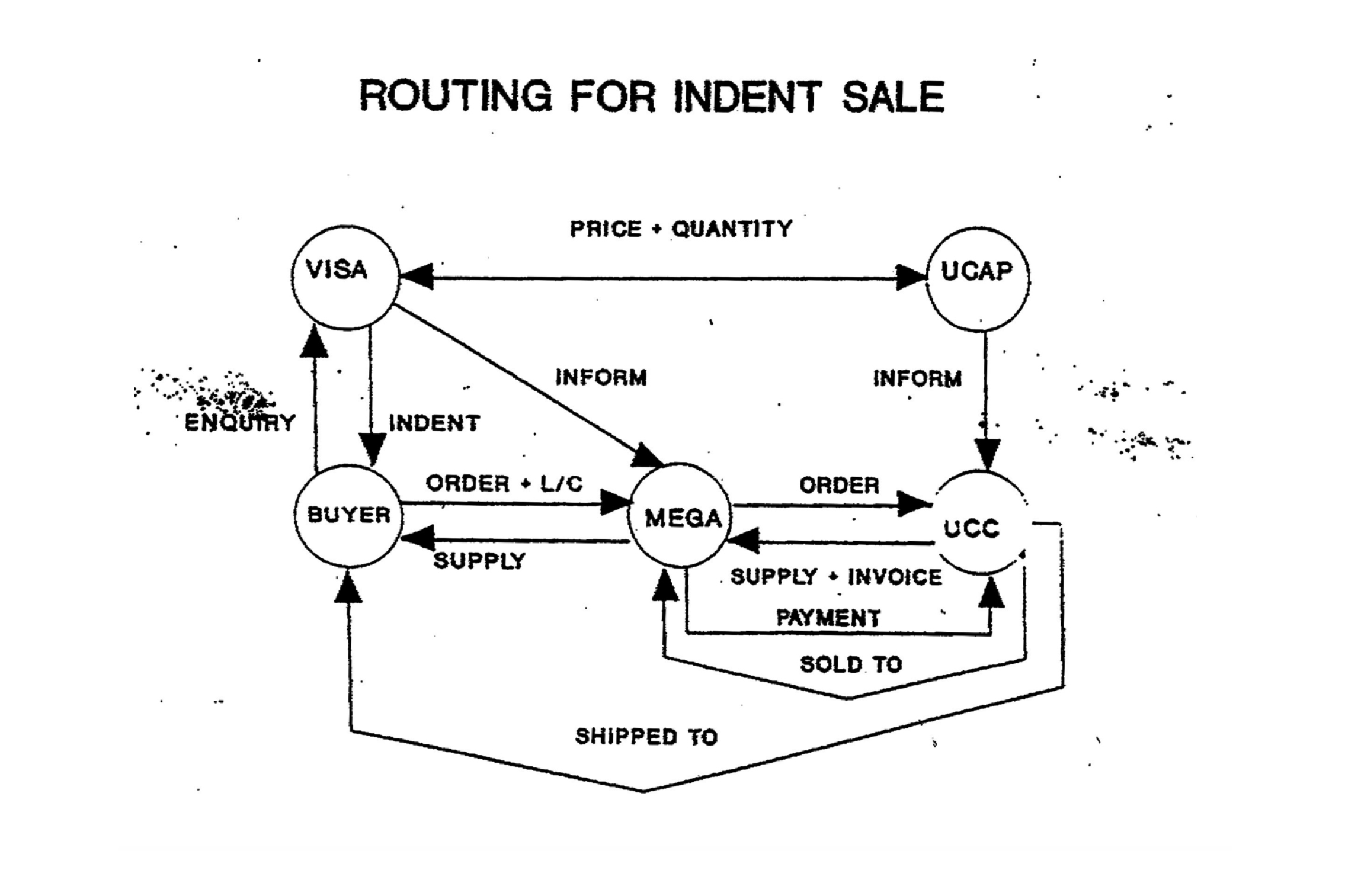

Visa Petrochemical would scout for customers. It would pass on formal price queries from potential customers to both Mega Global Services and Union Carbide Asia Pacific. They, in turn, sent them to the parent UCC, which would send the prices to Carbide Asia Pacific. The Asia-Pacific unit would further send that information to Visa Petrochemical which sent it to the customer.

If the buyer agreed, it would place the order with Mega Global Services. UCC would sell the product to Mega Global Services. UCC would arrange a third-party transporter, known as a “freight forwarder”, to ship the goods to the customer, according to the agreement. Visa Petrochemical would sign off on an indent – a document listing out the products imported – for the customer.

While the product originated from UCC warehouses, the seller on documents given at the Indian port was Mega Global Services, for which it earned a commission.

Mega Global Services was referred to as a “front party as a conduit” in internal correspondence. The majority of Mega Global Services’ business revolved around buying and then shipping UCC products as their own.

In 1998, it was replaced by a Singapore firm with a similar name – MegaVisa Solutions Pte Ltd. This too was owned by the Mittal Group.

A July 2001 email by a Dow India manager to his bosses in the US says, “MegaVisa Singapore entity was set up to take care of the post-Bhopal situation, and is essentially a shell company.”

MegaVisa Singapore bought UCC products in the US, “took title to them there, and then arranged to ship the products to our customers from there”, Sanjiv Sanghvi, director at the Singapore firm, submitted in a testimony to the US court in 2002.

This Mittal-owned network of “extended arms” and “shells” would ensure UCC’s products continued to be sold in the Indian market from 1993 to 2002. And among its customers were firms owned by the Indian government – the very party that was suing it for causing death and injuries to its citizens.

Government clients

Among UCC’s customers were wholly government-owned firms such as Gas Authority of India Ltd, Hindustan Photo Films Manufacturing Company Ltd and Hindustan Cables. Lubrizol India, then an equal joint venture between federal government-owned Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) and American chemical company Lubrizol, was also a customer.

Companies promoted by the governments of Gujarat (Gujarat Alkalies and Chemicals Ltd), Tamil Nadu (Indian Additives Ltd) and Madhya Pradesh (Vindhya Telelinks Ltd) also bought UCC’s products through the channel. The list of customers also includes more than 150 private firms, including Reliance Industries, Sterlite Industries, Finolex Cables, Crompton Greaves, Berger Paints and Castrol India.

Many of UCC’s buyers clearly knew who they were shaking hands with. Documents show UCC informed Oil and Natural Gas Company (ONGC) and IOC that the Houston-based Mega Global Services would bid on its behalf for a tender floated by the public sector companies.

“We hereby authorise Mega Global Services to quote against the above [ONGC’s] tender,” reads a letter, dated November 16, 1994, by Carbide Asia Pacific to ONGC’s general manager. Visa Petrochemical’s 1994 Annual Business Plan notes that the company managed a “breakthrough on TEG with ONGC”. TEG, or triethylene glycol, is a plasticiser chemical for which ONGC invited sellers.

“If MM Global Services is successful in winning the tender,” UCC’s December 1999 letter to IOC reads, “Union Carbide Corporation will supply the quantity required, and the product supplied will meet all the requirements of our specification.”

MegaVisa Singapore submitted a July 2001 sales invoice for an order for methyl isobutyl carbinol worth $77,656 by Lubrizol India. Lubrizol India was jointly owned by IOC and Lubrizol.

Visa Petrochemicals, which changed its name to MegaVisa Marketing and Solutions, worked closely with India’s Department of Telecommunications (DoT). “MegaVisa is working with DoT to improve OIT test in the specification,” reads one of Visa’s emails to Dow. OIT or oxidative induction time refers to a test to figure out the thermal stability of a wire.

UCC’s Indian front, in fact, had some level of influence on the government. An internal communication from MegaVisa to Dow from 2001, for example, states that “with a lot of groundwork”, the company managed to convince the Indian telecom department (DoT) to float a tender for the purchase of a cable product. This is a product that UCC, through MegaVisa, was supplying to the Indian market. “We need technical support from Dow [the US-based chemical giant had at this point taken over Union Carbide] to push DoT and Utilities for upgradation of specifications”, it says in the same note.

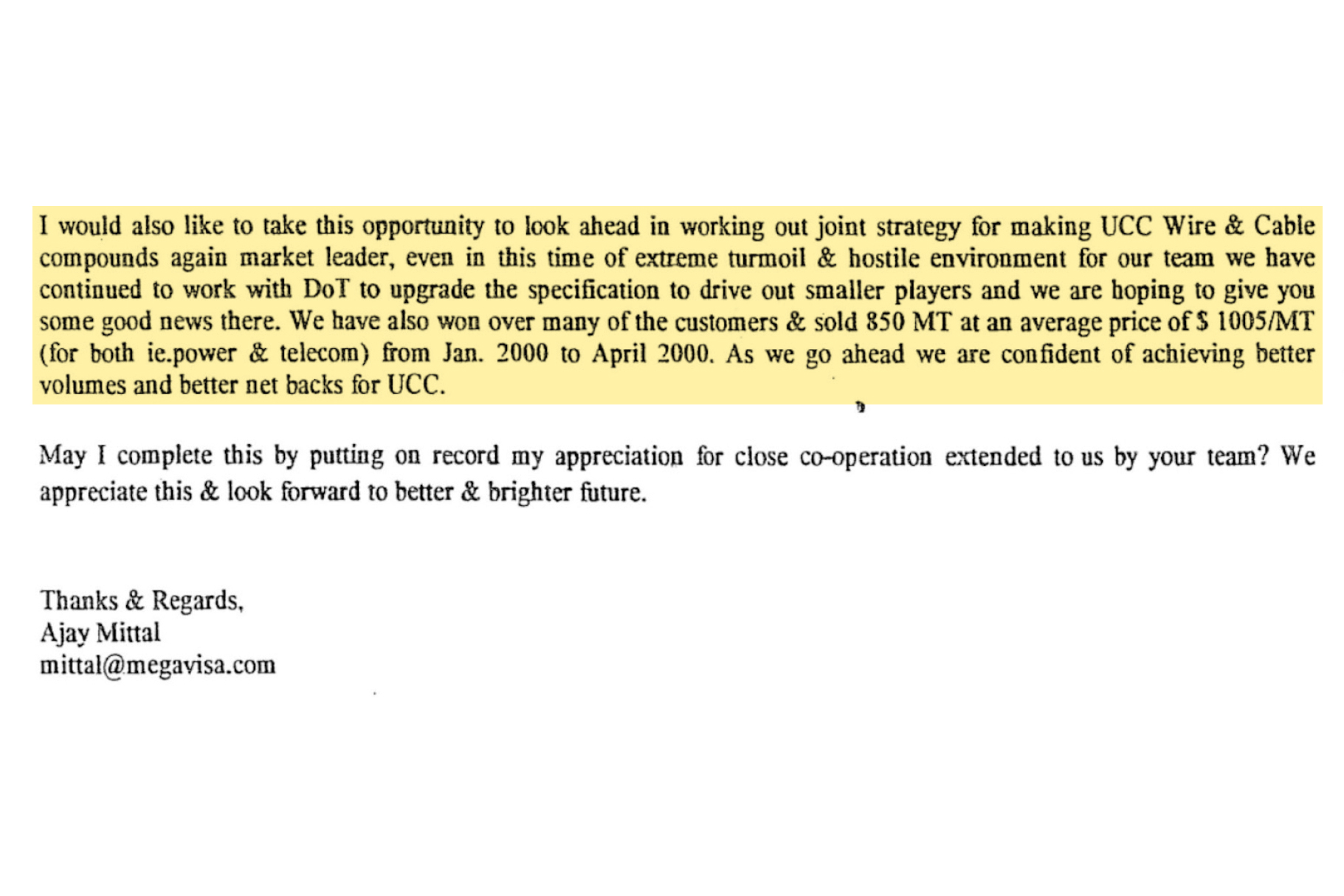

“Even in this time of extreme turmoil & hostile environment for our team we have continued to work with DoT,” Mittal said in an email to a UCC official on May 5, 2000. He also notes that MegaVisa’s work with DoT will help “drive out smaller players”. “As we go ahead we are confident of achieving better volumes and better netbacks for UCC,” he wrote.

Correspondence from two private firms – Sterlite and Finolex – show they too knew they were buying UCC products. Both firms sent legal notices to UCC and its subsidiary in the US, and Sterlite even filed a civil suit against the company after some orders they placed with UCC’s Houston-based front company Mega Global did not come through. The companies eventually settled the case out of court.

Mittal did not respond to queries from Al Jazeera. An Indian Oil Corporation spokesperson said the company “did not have any comments about the trailing communication”. All the other government and private firms that traded with Carbide’s front companies, including the DoT, did not respond to Al Jazeera’s queries.

Dow’s takeover

In February 2001, Dow bought UCC. Soon, activists demanded that the company come clean on why its fully owned subsidiary never faced trial and pay additional compensation to victims. Dow refused to take ownership of UCC’s liabilities, arguing that it never owned the Bhopal plant and that the latter is a separate legal entity.

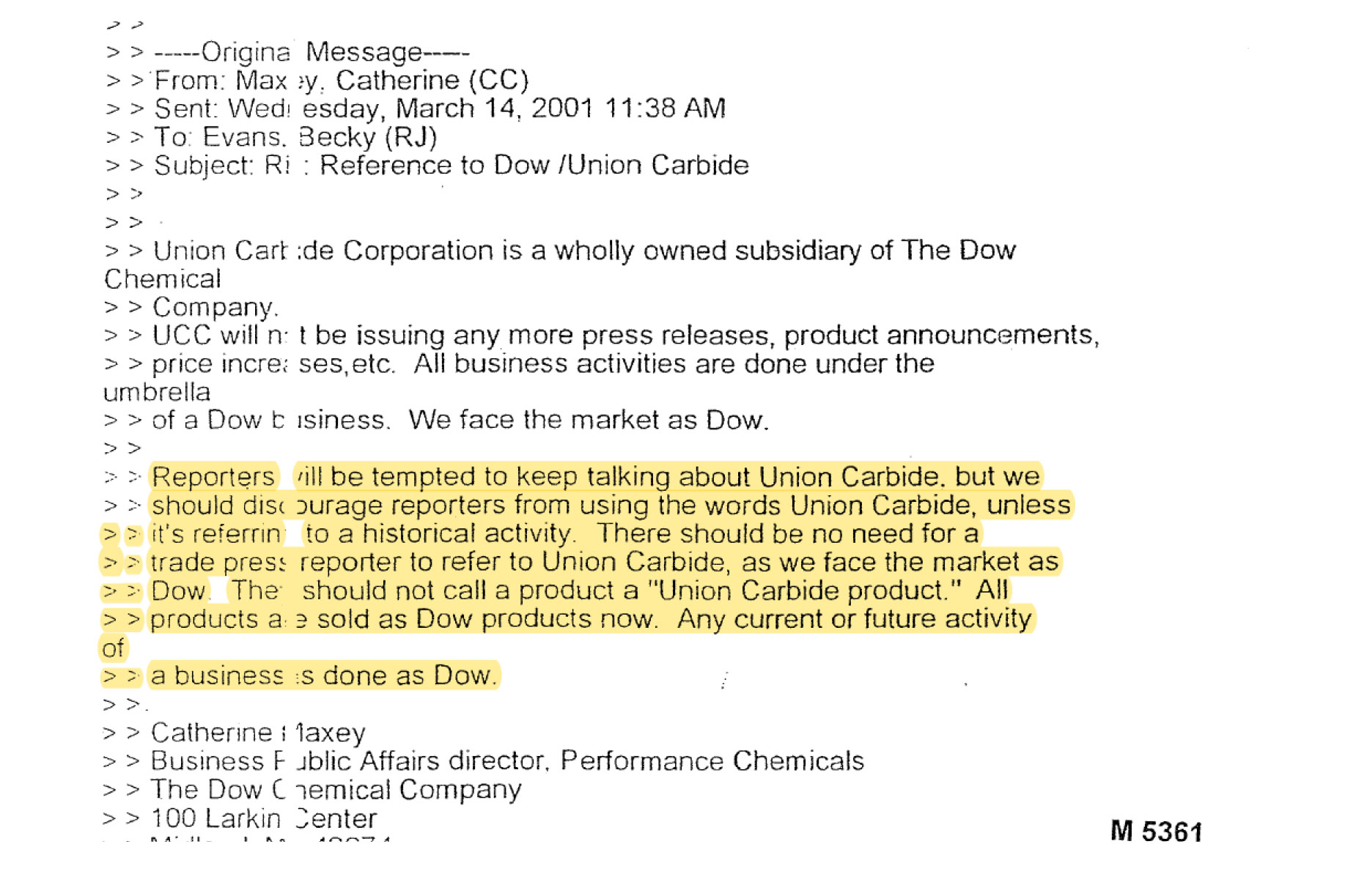

However, Dow also continued trading UCC’s products for a year using its intermediary companies. But it was keen to mask its link to UCC. An email by the company’s public affairs director in March 2001 reads, “Reporters will be tempted to keep talking about Union Carbide. But we should discourage reporters from using the words Union Carbide, unless it’s a reference to a historical activity.”

In January 2002, Dow (India) informed MegaVisa that it would no longer be the distributor of most UCC products. By this time, feedback from at least one Indian customer, Berger Paints, on MegaVisa’s personnel was not positive – referring to them as “non-committal”, documents show. Additionally, Dow’s India officials internally recommended that “major customers should be handled directly by Dow”.

MegaVisa, in turn, held Dow responsible for its losses. A year later, Houston- and Singapore-based MegaVisa firms filed a case against Dow and UCC on “antitrust” grounds in the US Connecticut District Court. The MegaVisa firms alleged Dow had gone back on its contractual obligations and hampered its profits.

Dow eventually settled with the Mittal-owned firms out of court, including the businesses in Houston, Singapore and India. The details of the settlement are not known. UCC’s Indian front MegaVisa filed for liquidation in 2010. Its finances reflect a company that was suffering losses.

The same year, the then Congress-led federal government moved India’s top court to change its 1989 order setting the compensation for the disaster’s victims. In its petition, it asked the Supreme Court to reconsider that amount and demand additional compensation jointly from UCC, Dow and Union Carbide India Limited. At the time, the victims’ representatives also demanded that the “corporate veil” of UCC, its subsidiaries and Dow be lifted. The case, pending for more than a decade, was last heard in October 2022 in which the Supreme Court asked the government to include the victims’ demands in its representation.

Shreegireesh Jalihal and Kumar Sambhav are members of The Reporters’ Collective.