Before Starfield, there was Delta V.

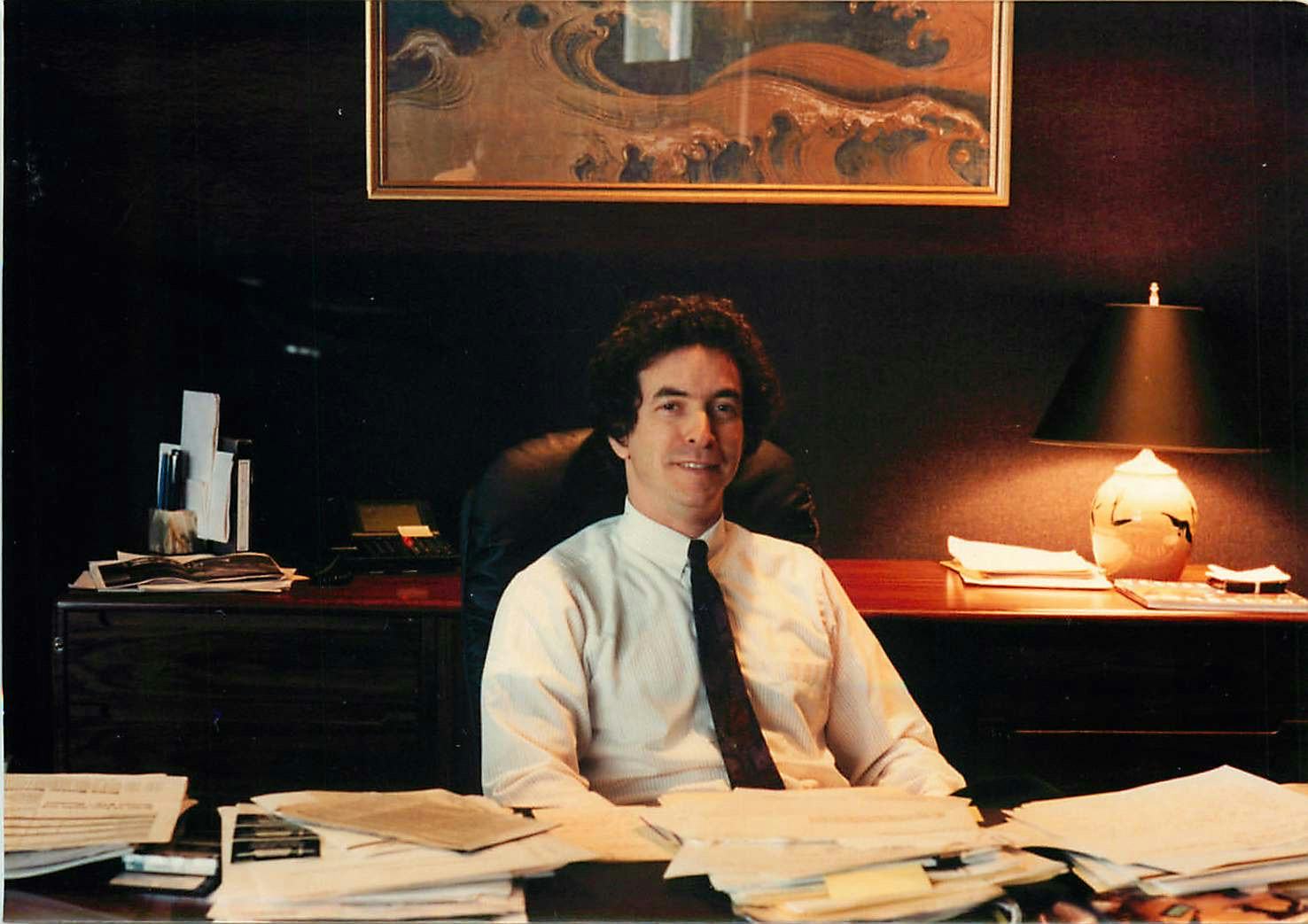

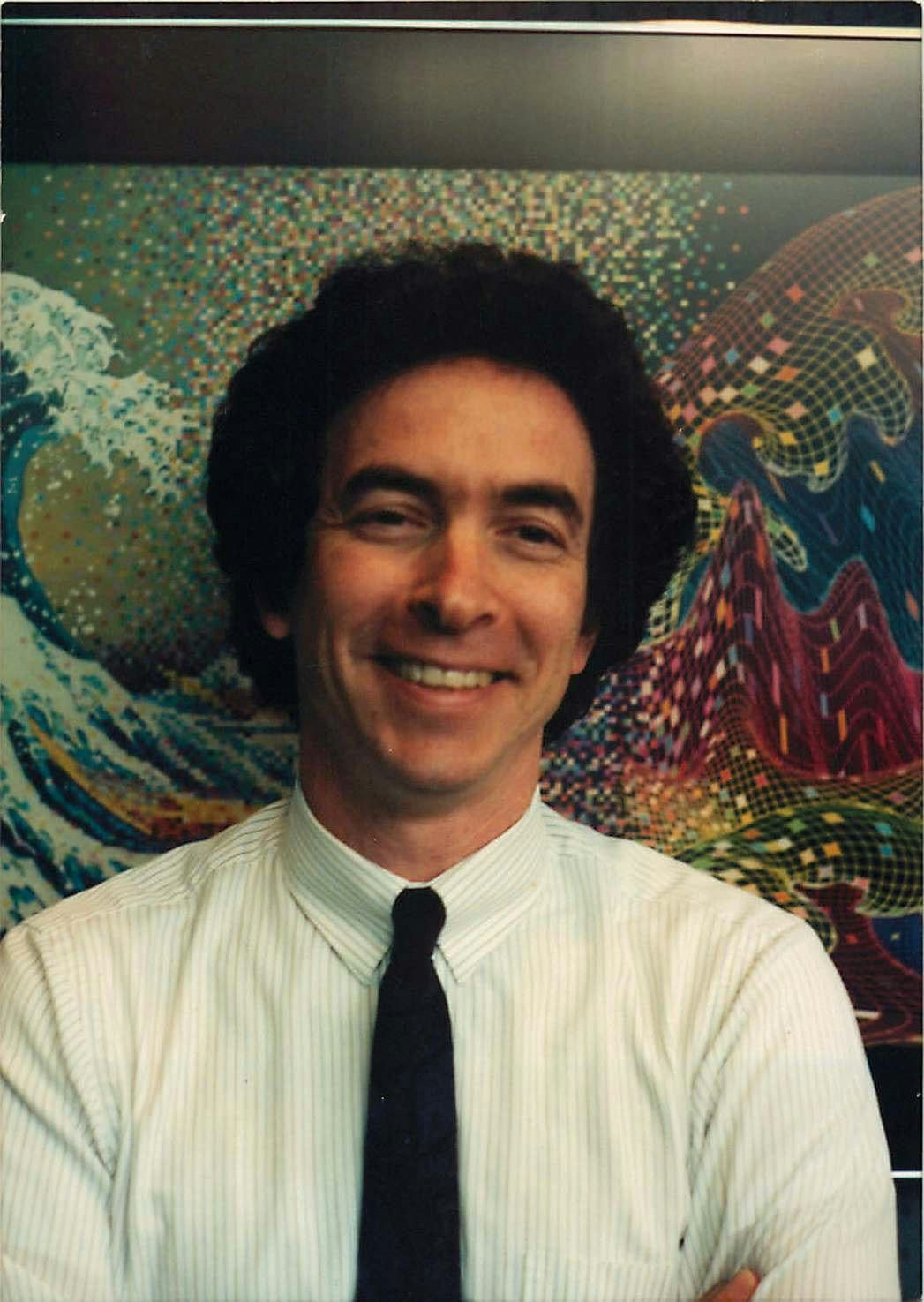

Bethesda Softworks’ latest video game (and its first original concept in a quarter of a century) is a massive open-world adventure boasting over 1,000 explorable planets in a future where humanity colonizes the Milky Way. But as Bethesda founder Christopher Weaver will tell you, Starfield isn’t the company’s first foray into space.

“We created Delta V many, many years ago [29 years ago, to be exact] and it was a massive space game,” Weaver tells Inverse. “We had a great time flying our little ships around the massive mothership, trying to have these furious firefights and stay out of the way of other people. To me, Starfield is basically Delta V on steroids.”

Weaver left Bethesda in 2002, and in the two decades since, he’s graduated from video game developer to a cross between historian, educator, and evangelist. (If this was Game of Thrones, he’d probably be a maester.)

Since 2016, Weaver has worked for the Smithsonian, recording the oral histories of gaming’s pioneers (including the creators of Atari, Pong, and other trailblazing inventions), many of whom are now in their 80s and 90s. “We've been very fortunate so far that nobody has died on my watch,” he says. More recently, he’s expanded his work at the museum, using video game tools to get young children interested in science and math through its Spark!Lab program. He’s also a research affiliate at MIT and teaches game development at Wesleyan University.

At age 72, Weaver considers himself to be part of the “second wave” of gaming pioneers. But his story can be traced back to the early days of the industry — and followed all the way to a future where gaming expands far beyond its current confines to change not just the entertainment industry, but the world.

Christopher Weaver’s path to video games begins with a forgotten company called Miscellaneous Magic, which, despite its name, was a lot less glamorous than you might think. Miscellaneous Magic was a Saudi-backed research project in the late 1970s and early ’80s looking into the types of technology we take for granted today.

“It was, how do you build a touch-sensitive interactive? We were creating new forms of interface and screens that, until that time, had barely existed outside of the military,” Weaver says.

But, according to Weaver, Miscellaneous Magic wasn’t moving fast enough and the Saudis pulled the plug. Weaver was able to buy up some of the technology they’d been working on, including a then-cutting-edge PDP 11 computer, “which was pretty substantive hardware in those days for a small company.” After moving from their “very nice offices” in Rockville, Maryland, into Weaver’s house, the remaining team launched a consulting company — with no intention of creating video games.

From this point, the history of Bethesda is well documented. While most of the team was focused on creating simulations for the military and other ways to make money, one of them decided to take things in a different direction.

“Ed Fletcher was a Florida Gators fan,” Weaver says. “He asked me whether or not he could just build a software product that would play football.”

“People were telling us that there was no possible way we could fit Dungeons and Dragons into a computer.”

Using the PDP 11, Fletcher created Gridiron, believed to be the first-ever physics-based sports simulation. Technically, Gridiron predates Bethesda itself, but after seeing the success of the football simulator, Weaver and the rest of the team decided to see if they could apply the same technology to another sport: hockey.

Weaver and his co-workers started attending Washington Capitals games, dressed in suits and taking copious notes. “People who were sitting not too far from us would ask us if we were with the government,” he says. In 1988, Bethesda Softworks released Wayne Gretzky Hockey and never looked back.

Thirty-five years later, Bethesda isn’t exactly known for sports games. Today, the company’s reputation is built on open-world adventures set in fictional worlds of fantasy, post-apocalypse, and (now) space. Weaver was there for that chapter too, starting with The Elder Scrolls: Arena in 1994. But like so much in the early days of Bethesda, the path to success wasn’t as direct as you might expect.

“There are pieces of music that were done on a dare,” Weaver says of Arena, with a dramatic flourish. “People were telling us that there was no possible way we could fit Dungeons and Dragons into a computer.”

Bethesda went on to release more than 20 games and expansions in the Elder Scrolls franchise while also applying similar design concepts to the Fallout series, set in the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust. Weaver was around for the first three Elder Scrolls games before he left the company, now owned by Microsoft.

But while Bethesda’s claim to fame might be the one-two-punch of Elder Scrolls and Fallout, Weaver is just as proud of the company’s less-celebrated creations. Case in point: an early foray into accessibility when Bethesda became one of the first video game companies to implement subtitles for deaf gamers. “It seemed like a no-brainer,” Weaver says.

The concept came about after Bethesda hired two deaf employees and encouraged them to explore the concept, says Weaver. Building the technology was relatively simple, and the company made it open-source, so anyone could use it for their own games. Even today, open-source subtitle tools are uncommon — most studios build their own for each new game or proprietary engine.

“A few people did something with it. Not enough, in my opinion.”

Fast-forward to the summer of 2023, and, within the massive archives of the Smithsonian, Christopher Weaver is building something unprecedented: a sprawling oral history of the origins of video games.

The project was inspired by Ralph Baer, the inventor of the “Brown Box” considered to be the forerunner to the console video game system. After becoming friends, Weaver agreed to interview Baer for a definitive history, but the prolific inventor died in 2014 before they could start the project. Afterward, Weaver took the concept to the Smithsonian with the expanded pitch of interviewing an entire generation of pioneers before it was too late.

“As the old historian in this area for the Smithsonian, I've had the magnificent pleasure of talking to a lot of these people, many of whom I knew — and many of the older ones who I didn't,” Weaver says. “It's really been an honor to do their oral histories.”

Roughly 75 percent of the planned interviews have already been completed, including Atari co-founders Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney (who died in 2018 after completing his interview), Pong creator Allan Alcorn, Warren Robinett (who made Adventure, one of the world’s first graphical adventure video games), and much of the team behind 1962’s Spacewar!, credited as the first video game ever played on multiple computers.

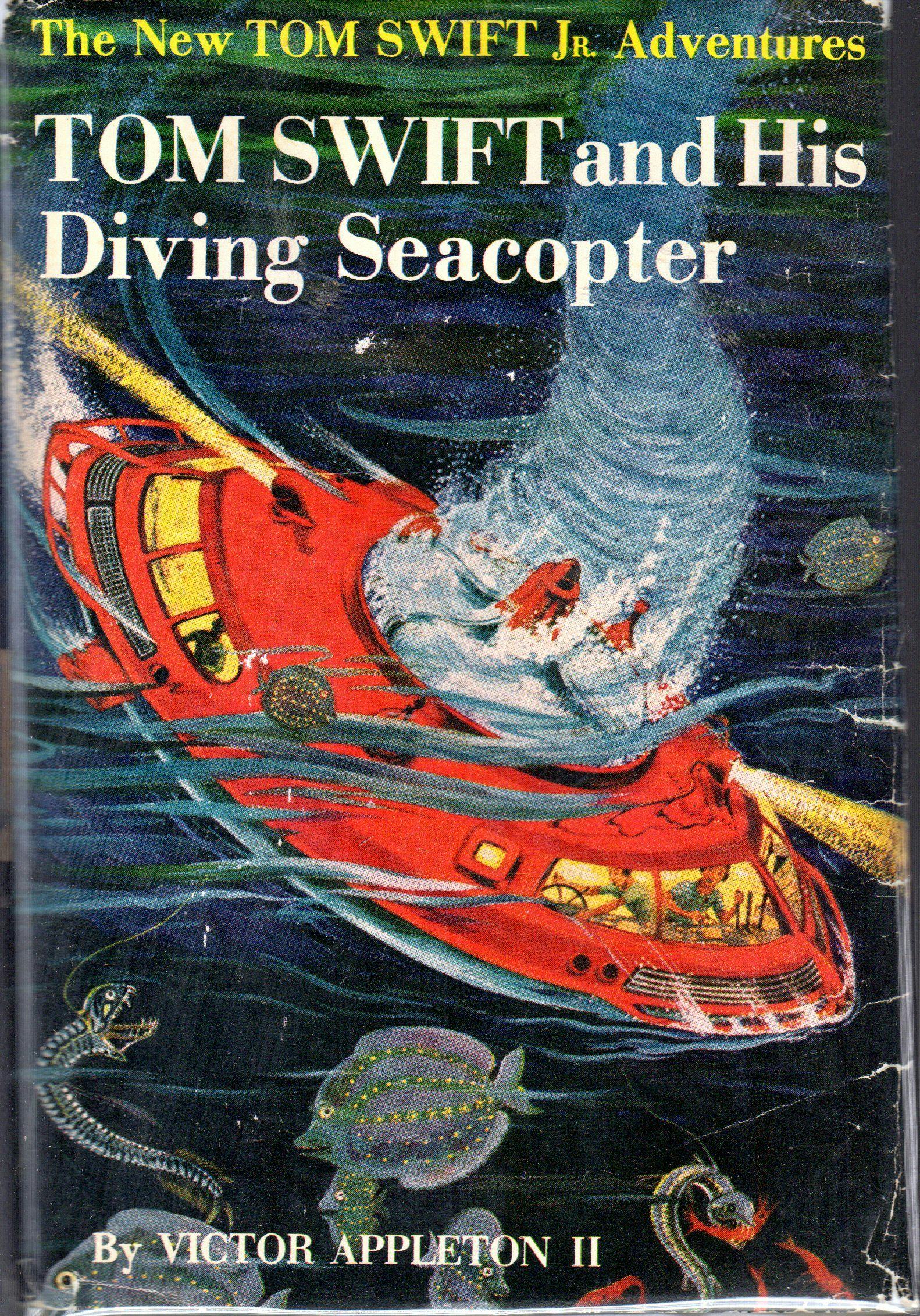

The project is ongoing, and most of it remains locked behind slow-moving institutional bureaucracy, but Weaver has already begun to notice some interesting patterns. For example, a lot of the industry’s pioneers shared a love for the Tom Swift books, a series of science-fiction and adventure stories published from the 1910s onward that explored topics like outer space, underwater exploration, and something called a “G-Force Inverter.”

“When these inventors were of grade-school age, if they read Tom Swift, their creative juices were put on steroids,” Weaver says.

Once the work of recording these oral histories is done, curators will likely step in and come up with some sort of exhibit. But that’s not really Weaver’s concern. He envisions an accessible digital archive where researchers and historians can learn about the origins of the industry, straight from its creators.

“While history is often written about with great authority, the reality is that history by its nature is inherently anecdotal,” Weaver says. “We've had an opportunity to interview the people who actually created an entire industry, in their own words. Long after all of us are dead, the future of our industry is cemented in the words of the people who created it.”

In recent years, Weaver’s work at the Smithsonian has also expanded beyond video game history. As a member of the advisory board of the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, located within the Smithsonian, he’s taken on a key role in the expansion of a very different type of project: Spark!Lab, a replicable interactive museum exhibit designed to get elementary-school-aged children excited about math and science.

For Weaver, it's an opportunity to take the tools of video games, some of which he helped invent, and apply them to a nobler purpose. He specifically points to the concept of the leaderboard, which transcends the medium from classic arcade games to Fortnite rankings, as a system that could be used to steer more kids into STEM careers.

“Think of the traction that will generate among an entire young population utilizing a primary game tool that we've used for generation after generation,” Weaver says. “We're just reapplying it here for a different social purpose.”

Spark!Lab may just be one brick on the path to a future where video games barely resemble anything we know today. From the rise of artificial intelligence to a new generation that grew up on gaming, Weaver believes the industry is on the precipice of a fundamental shift.

“We are scratching the surface of the power of games and computation applied to training and education,” he says. “I mean, we are Neanderthals right now and we are scraping by.”

“Ten years from now, game designers and makers will look back and basically think of us as using quill pens and ink.”

Ask anyone in the industry right now, and there’s a decent chance they’ll say the biggest shift coming for gaming is AI. For Weaver, his experience with products like ChatGPT dates back to the very first version, a primitive “chatterbot” called ELIZA created in the 1960s by Joseph Weizenbaum, an old friend and MIT colleague.

Since then, the technology has grown exponentially. Weaver predicts we’ll see “three or four technical generations” of AI development within the next decade, leading to some pretty incredible innovations.

“Generative AI will allow games to be immersive on a level that you can barely imagine today,” he says. “As the simulation becomes closer and closer to what we would consider reality, we can create sort of a hyper-reality in the player’s mind. And that is an amazing prospect. Ten years from now, game designers and makers will look back and basically think of us as using quill pens and ink.”

AI will undoubtedly have a huge effect on gaming, but Weaver is less concerned with what that means for the next generation of first-person shooters and vast open worlds.

“I don't care about AAA games anymore,” he says. “It's not like there aren't important games. There are. But my interest is having seen how amazingly influential the technology behind video games can be.”

But regardless of where video games go next, Christopher Weaver is confident that the company he founded will soldier on, thanks in part to all the great people who helped build Bethesda with him. From Delta V all the way to Starfield, the future seems limitless. And it’s only getting better.

“The wonderful thing about Bethesda is so many of the designers and programmers have been there over 25 years,” Weaver says. “You've got some great storytellers there, and they have a lot of great history and a deep library — only part of which you've ever seen.”