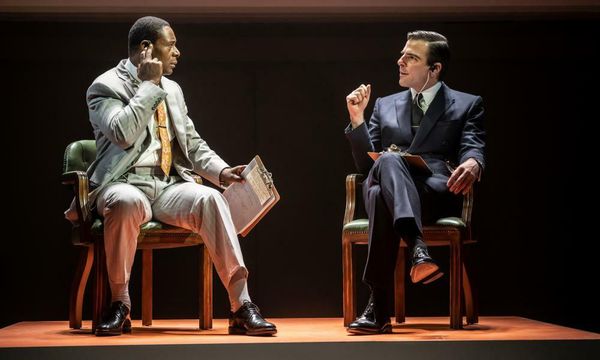

David Harewood and Zachary Quinto

(Picture: Johan Persson)James Graham’s dynamic, intoxicatingly thoughtful play traces the corruption of modern political discourse back to 1968. Specifically, the adversarial televised debates between the gay, liberal writer Gore Vidal and the conservative polemicist William F Buckley Jr during the Republican and Democratic Presidential conferences that year, which culminated with the two men calling one another “crypto-Nazi” and “queer”, live, to 10 million homes.

The play’s decoding of the way politics, media and fame interact has deepened since its original run at the Young Vic in 2021. No one under 60 will remember the debates, or what Vidal and Buckley stood for, but Graham stitches them back into the wider context of the Vietnam War, student demonstrations, racial tensions and the assassinations of John and Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr, with great finesse.

David Harewood reprises his superlative performance as Buckley, finding dignity in the man’s pomposity and extravagant facial tics. That a black actor is playing a patrician, white conservative initially adds an illuminating filter to the play’s themes. Before long, Harewood’s skill and charisma supersede such thoughts.

This time he’s opposite US actor Zachary Quinto as a purringly self-satisfied, borderline-cruel Vidal – less charming than his predecessor in the production, Charles Edwards, but ultimately much more vivid. Seamlessly directed by Jeremy Herrin and stylishly designed by Bunny Christie, it’s a dazzling night out altogether.

The two protagonists are surely barely remembered here now by anyone without a freedom pass: Graham, who is 40, was alerted to their debates by the 2015 documentary, also called Best of Enemies, by Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon. But as in his current musical Tammy Faye, and his TV drama Brexit: The Uncivil War, Graham discerned the impact apparently peripheral figures could have on events.

The broad strokes of the story also chime neatly with British and American society today. Then as now, identity politics, and the right to free speech and to protest, were hot-button cultural issues. There was a gulf between young and old, the dominant parties were split, and very rich men claimed to have the poor’s best interests at heart.

The ABC network, flagging behind rivals NBC and CBS, decided to introduce opinion to neutral news but their two “public intellectuals” soon started tearing chunks out of each other. The public liked it. Their favoured parties liked it. Vidal and Buckley found that they liked it too.

Cameos from Andy Warhol, Aretha Franklin and James Baldwin offer an alternative commentary on celebrity and influence. But again, Graham is more interested in the peripheral or the forgotten than those whom history reveres. John Hodgkinson gets two great turns as ABC anchor Howard K Smith and Chicago’s autocratic Mayor Richard J Daley. Warhol, I think, gets 15 seconds of dialogue here rather than the 15 minutes of fame he predicted for everybody.

The supporting characters often morph into their real-life, filmed counterparts on Christie’s set, where glass-windowed edit suites become retro TV screens. In an epilogue, the long-dead protagonists set aside their rancour and reflect on where the ratings-driven hunger for charismatic contrarians has got us now. Again, this scene seems much more organic and moving than it did first time round. I really can’t fault Herrin’s bold, pacy production, or the canniness and flair of Graham’s writing here. Bravo.