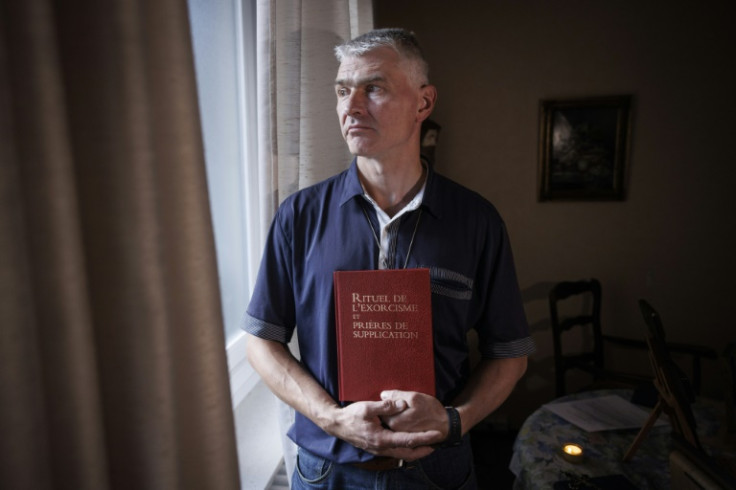

Thierry Moser, Catholic priest and exorcist, has a twin mission: to ease people's torment through prayer -- and challenge old cliches about a practice he sees as an answer to very modern ills.

Originally trained in clinical psychology, Moser was ordained priest in 2009 and officiates in Belgium's capital where he performs exorcisms for around 200 faithful each year -- and struggles to keep up with demand.

What do they have in common? "All feel under attack from the devil, and are looking to be set free," he told AFP in an interview coinciding with Pope Francis' visit to the country.

Interest in exorcism has rebounded in recent decades.

In 2014, a year after Francis was elected, the Vatican formally recognised the International Association of Exorcists -- in what experts say amounts to a papal blessing.

Today, the practice is well-established in Belgium, where bishops across the country's eight Catholic dioceses have each mandated a priest to offer exorcism sessions.

There is no overall figure for the number of people who have resorted to exorcism in the country.

But the Flemish abbey of Averbode in Belgium's northeast has emerged as something of an epicentre, fielding more than 1,000 requests each year according to Kristof Smeyers, who researches the history of magic, science and religion at the Catholic University in Leuven.

People from all walks of life come to Moser for help, he says. Some are Catholic, but others are not.

Moser receives them in a space made available by religious authorities in the working-class Marolles area of Brussels, with a team of five staffing his "ministry of exorcism" set up with blessing from the Catholic hierarchy.

"Our first concern is to welcome people without judgement," he said.

Their "demons" take many shapes.

Many are dealing with setbacks in their personal or professional lives. Others struggle with phobias, nightmares, or physical symptoms ranging from unexplained pain to tinnitus.

"I feel like we are a kind of field hospital for the Church," mused Jacques Beckand, a deacon who was trained to perform exorcisms in the French city of Lyon and joined Moser's team a year ago.

"We see people who are grappling with tough spiritual challenges, with temptations, and we try to bring them healing as best we can."

Dating back to the earliest days of Christianity, the practice of casting out demons through exorcism was used by Jesus Christ and his disciples according to the Gospel.

It fell out of favour with the Church during the 20th century -- until it was catapulted back into public view with the release of William Friedkin's chilling blockbuster "The Exorcist" in 1973.

"In the immediate aftermath of that film coming into cinemas, there's a sudden incline of people demanding exorcisms or feeling possessed -- or thinking that someone in their family is possessed," said Smeyers.

A second factor behind the resurgence was the rise since the 1980s of US televangelism, with highly theatrical exorcisms performed in public by ministers of various Protestant faiths.

"The Catholic Church felt that pressure a little bit from the evangelical movement" with its "idea that you can be delivered from evil if you feel you live a sinful life", said Smeyers.

Within Moser's team in Brussels, an exorcism follows a set pattern.

First a preparatory prayer between the officiants, who work in teams of two.

After that, the prayer session continues to include the person seeking help, with chanting sometimes incorporated as well.

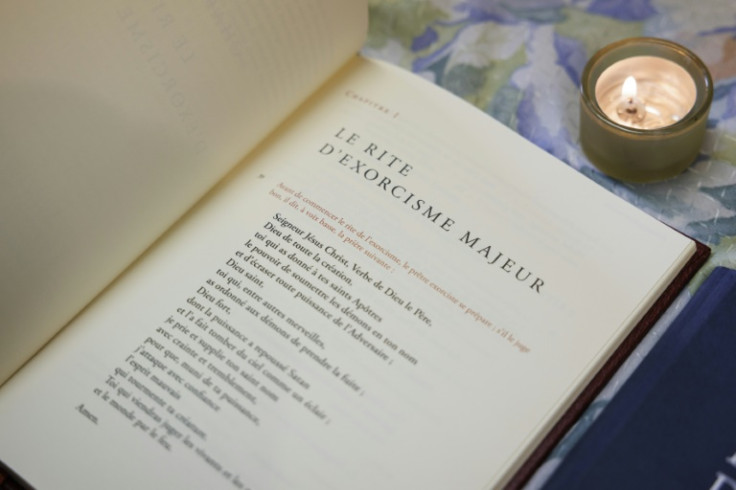

At the heart of the practice is the solemn reading of a text known as the Rite of Major Exorcism, which can only be proclaimed with express permission from the Catholic hierarchy.

"We are not magicians," said Beckand. "We don't have magic tricks or formulas. But what we do is place people back in their relationship with God."