The water crisis at Flint, a town in Michigan, US in 2014 has focused public attention on the dangers of lead exposure, especially in children. A late 2016 investigation found that nearly 3,000 other communities in the US had even worse lead water levels than Flint. A recently published study claims that “half of US population was exposed to adverse lead levels in early childhood”.

Lead exposure during the critical brain development window between the ages one and five has the most adverse effects on humans, causing irreversible and permanent brain damage. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 500,000 children under the age of six have blood-lead levels that exceed the “reference level”, as it’s called.

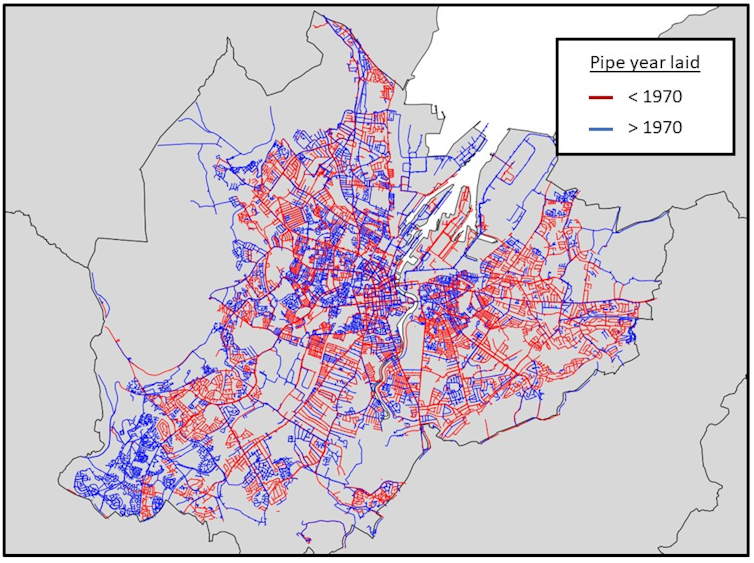

The UK and Ireland have largely escaped the same scrutiny even though lead water pipes were used ubiquitously in homes and community water systems prior to 1970. The early 20th century “great lead water pipe disaster” in Glasgow was neither particular to the city nor the time.

High lead levels in the city’s water supply were known to scientists as early as 1855, but water regulators ignored them and touted the supply as the “purest water in the world”. But Glasgow’s water supply became associated with negative health effects, from heart and kidney disease to “mental retardation” among children. It wasn’t until 1979 that the water was treated with lime which saw median blood-lead levels drop by 61%.

Here on our doorstep in Belfast, there is a potentially alarming but little-known public health issue growing. As our small-sample water tests make clear, while leaded water lies buried within our infrastructure, children are still being exposed to harmful levels of lead.

We are now about to undertake a bigger investigation that will reveal the extent of lead in Belfast’s water.

Risks and harms

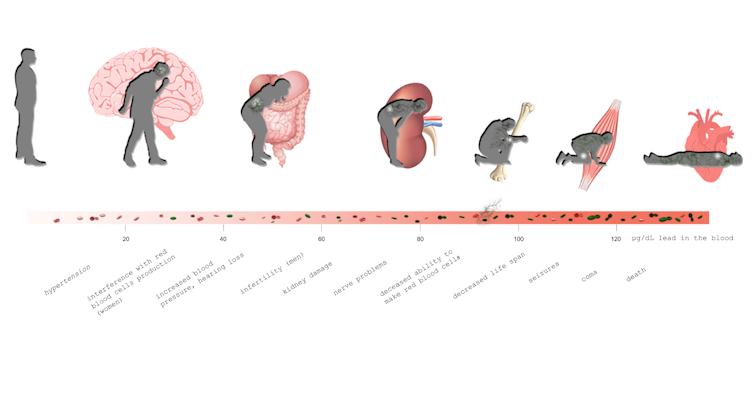

There is plenty of evidence to show the physical, emotional, and developmental harms of lead, even at levels well below what is judged to be officially acceptable.

One study found that even for children who tested under 5 µgPb/dL (micrograms per decalitre or parts per billion) – the point that triggers UK level of concern – they could expect significant declines in IQ.

Other studies have found that children under the limit could also expect increased social and behavioural problems such as ADHD, juvenile delinquency and criminality, plus an array of physical harms including coordination difficulties, kidney damage, reproductive issues, hearing and speech problems, and even an increased prevalence of cancer.

Studies have correlated above standard blood-lead levels to violence. One correlated high violent crime rates in New York in the 1970s and 1980s to lead exposure.

Worsening lead levels

The UK reference level for lead are the necessary product of the ubiquity of “three Ps” of lead in 20th-century urban life: petrol, paint and pipes. While these products have been regulated out of use, their vestiges remain layered in the infrastructure of everyday life in the UK, slowly poisoning people.

As more evidence-based studies make clear, any lead in the body causes observable harm, even levels well below the reference limit act as neuro-toxins, and the effects are permanent. A prominent lead researcher has called such standards a “risk management tool rather than a threshold for intoxity”. In other words, no level is non-toxic or safe for children.

Our preliminary research randomly sampled water from 35 houses in Belfast. Mindful that the UK reference limit is 10 µgPb/L, we found five test results or 15%, exceeded the reference limit, and four exceeded 50 µgPb/L with a maximum of 95.2 µgPb/L.

Notably all tests found some lead in the system. The false economy of safety of water under 10 µgPb/L is one derived from the ubiquity of lead in our urban spaces and the cost of cleansing that environment of it.

No epidemiological study of the prevalence of lead water or poisoning has ever taken place in Northern Ireland. NI Water told us it bases its level of concern from studies that have taken place in England.

Without a specific study in Northern Ireland it is difficult to gauge the magnitude and scale of the effects lead contaminated water is having in Belfast, though NI Water admits that an estimated 100,000 homes in Northern Ireland might be receiving water contaminated by lead. These are clustered in older built-up areas of Victorian and Edwardian houses, but one should assume any house built before 1969 has lead pipes and therefore leaded water.

Raising awareness

The question is, why is this not a high-profile public health issue? Where are the campaigns to raise awareness and educate people about what they should do?

Given the number of old buildings and homes in Belfast and the UK more generally, this is not an isolated incident. It is estimated that 25% of all service pipes in the UK are lead. Ageing pipes, road traffic pollution and drinking water acidity can leach higher lead concentrations into the water.

In short, for adults in Belfast, this isn’t necessarily the water they drank as a child. The city tacitly recognises the severity of the impact of lead pipes on public health as it now systematically, street by street, replaces the lead service pipes over a 20-year period, but only to the property boundary.

It is not doing enough to warn its citizens that they should cautiously drink the water, filter it with activated carbon, or flush the pipes before each use, despite the now-closed Health Protection Agency (HPA) highlighting its own prevention awareness shortcomings in 2009. Under funding of water service providers likely limits such outreach.

Even if the lead water service pipes are replaced, lead pipelines in homes must still be identified and replaced by the homeowner in NI. Under current regulations, if landlords and homeowners are aware of lead water lines, they do not have to share this information with tenants or during the sale of the home.

With rising inflation and the associated increased construction costs, supply chain issues and low supply of contractors, homeowners may postpone or indefinitely hold off testing their water and replacing home lead water lines thereby further concealing the problem.

Lead contaminated water is a silent crisis. And our cities are complicit in producing the next generation of children who might underperform, be prone to violence, or suffer debilitating bodily harm. The US has been having this conversation about exposure to lead in water for a decade; it is time we did too.

Tristan Sturm receives funding from an ESRC Impact Grant.

Jeremy Auerbach receives funding from the QUB/ESRC Impact Acceleration Account.

Nuala Flood receives funding from the QUB/ESRC Impact Acceleration Account.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.