The 24th Winter Olympic Games are underway in the Chinese capital, but winter itself seems far away. To counter the lack of cold weather, the organisers are using vast quantities of water and energy to supply the events with fake snow.

What are the consequences of maintaining artificial winter conditions on this scale? Madeleine Orr, a sport ecologist in the Institute for Sport Business at Loughborough University, considers the tournament’s environmental scorecard.

We spoke to her for The Conversation Weekly podcast.

How important is the local climate in Winter Olympic Games?

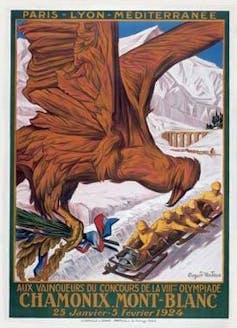

The first Winter Olympics took place in 1924 in Chamonix – a town in the French Alps. All the events happened outdoors. The Games organisers flooded courses to create natural rinks for ice hockey and tracks for sledding sports. There was plenty of fresh powder snow for skiing, too.

More recent Games have used significant amounts of artificial snow. Olympic snow makers have said that Sochi 2014 was about 80% fake and in Pyeongchang 2018, closer to 90%. Now we’re watching a Winter Olympic Games in Beijing with 100% artificial snow, which is unprecedented. There’s a whole range of questions that this raises in terms of the safety and competitiveness for athletes and the environmental cost of the Games.

The last few Olympics were poorly chosen for their natural conditions. Climate change has increased the temperature and shifted precipitation patterns in Beijing, but not so significantly that conditions are substantially different to what they were ten years ago when the bid was advanced. A Winter Olympic Games here was always going to rely on artificial snow because Beijing and Zhangjiakou (the mountain city in Hebei province which will host skiing events) are just not that snowy. And in that case, snowmaking is a great stop-gap solution: you can produce snow, you can’t produce cold temperatures.

Since the 1960s, ski resorts have increasingly relied on artificial snow. To survive, resorts must be able to open about 100 days of the year. That window is getting very tight. In Europe, for example, the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research found that about 12 days have been lost from the beginning of the season and 26 days from the end since 1970 in the Swiss Alps. In North America, we’re seeing similar numbers.

The northern hemisphere has lost about four million square kilometres of spring snow cover – about a 10% decrease over the last four decades. Artificial snowmaking has been the solution. And that’s what we’re seeing in Beijing. But if these trends continue and in 40 years the world loses another 10%, or if winter temperatures continue rising, snowmaking may not be able to make up the difference.

What goes into making fake snow?

At these Olympics, seven machine rooms and pumping stations move water up mountains where it’s pushed through high-pressure pumps, then forced, with air, through a fan and blasted out of more than 350 snow guns. It falls on the ground and typically has chemical additives that help it bind together, but in these Games, snow makers have claimed there are no chemicals involved. A team of groomers spread the snow around.

The Chinese organisers have used reservoirs of water that have been collecting rain and runoff for a long time, and they claim to not be pulling from general sources of drinking water. This was contested by local newspapers which reported on rivers being diverted to accommodate the fake snowmaking, and officials have reportedly shut off irrigation to farmland to conserve groundwater. But for the most part, it seems the event organisers are pulling from predetermined reservoirs.

China has claimed the Games will be 100% powered by green energy, and Beijing organisers have gone to great lengths to secure access to renewables. An analysis by the website Carbon Brief suggested that Zhangjiakou can generate more green energy than most countries and its pioneering grid system can deliver electricity to Beijing and neighbouring regions.

Still, when the Games end and the cameras leave, how will China continue to power the dozens of ski resorts and skating rinks built across the country to meet its bid promise of bringing 300 million new participants into winter sports?

All told, maintaining a supply of fake snow is a complicated technical solution sustained with a lot of energy and more than 49 million gallons of water – enough to fill 800 Olympic swimming pools.

What will the effect of all that water use be?

If the region has enough warm days and snow melts, water use could really climb. The estimates provided by the Beijing 2022 organising committee suggest that the Games will draw on 4% of available water in Yanqing and 2.6% in Zhangjiakou. It’s a stark number and it’s buried deep in the report. But researchers at the University of Strasbourg and some in China reported that water use could be higher than that, depending on how the Games go.

The Paralympic Games take place a month later when it’s likely to be a bit warmer and drier anyway. Fake snow production might ramp up at that point.

And then there’s a big question around what happens when that much snow melts.

Roughly 800,000 square metres of typically dry terrain will be covered by fake snow. The water table could accommodate a bit of meltwater, but probably not that much, particularly if it melts quickly. It’s very hard to say exactly what that would look like because most research has considered situations with natural snow and some artificial snow mixed in. Researchers haven’t examined the consequences of 100% fake snow melting rapidly. So this is a bit of a test case. We do know the organisers are planning on recapturing water when the snow melts, but it’s impossible to catch all of it.

Previous research suggests that there will be some sediment erosion and some loss of plant life, or changes to the arrangement of plant species, which could harm wildlife in the region. But it’s too early to tell what the scope of that will be.

What else can you say about the region’s wildlife?

The Games take place next to the Songshan National Nature Reserve and 20,000 trees were felled to make room for some of the events. The reserve was previously off-limits to visitors by Chinese law, and to accommodate the Games, the boundaries of the reserve were redrawn, causing an uproar among local biologists. I think they replanted close to 80% of those trees elsewhere, but biodiversity loss within the reserve – particularly around alpine meadows and certain rare species that grow there – is undeniable.

It’s been very hard to find any translated information on this emanating from the Chinese government.

Listen to Madeleine Orr speaking about her research on The Conversation Weekly podcast.

What do the athletes make of all this?

Beijing 2022 definitely lacks a winter vibe. Some of the skiing and sledding facilities are surrounded by a lot of brown mountains and industrial space, which is what athletes have been documenting on TikTok and Twitter. There’s a strange atmosphere around this winter event in a decidedly non-wintery environment.

We interviewed a number of athletes from different winter sports to find out their concerns. A lot of them – particularly downhill sportspeople – were quite excited to be competing on artificial snow, because it’s fast and hard. Biathletes and cross-country skiers were more worried about injuries.

That’s because artificial snow is about 70% ice. Natural snow, by comparison, is about 30% ice. It’s a softer surface to fall on and move through. It’s less gritty on the bottom of your ski or your board. When you fall on a harder surface you risk bigger injuries.

A growing number of outdoor athletes are concerned about the environment. We often think about farmers and fishers being on the frontline of climate change because they work outside. Athletes are outside for several hours every single day training. Winter athletes in particular tend to compete in places that are at a high altitude and see a lot of snow. In some cases, they have a front-row seat to melting glaciers.

The International Biathlon Union just put out a survey showing a huge majority of their members were either very concerned or extremely concerned about climate change. Most were willing to make changes in order to lead less carbon-intensive lifestyles. We are really starting to see how worried athletes are in the survey data.

How might future Winter Olympic Games change?

The International Olympic Committee promises to halve its emissions by 2030 and go carbon-neutral by 2040. All future hosts will be contractually obliged to meet these goals, and the Parisian hosts of the 2024 Summer Games have said they will be “climate-positive”.

It’ll be exciting to see how the Committee makes this work, but it’s going to be difficult if they keep holding the Winter Games in places that need to use a lot of water and energy to recreate the traditional winter environment.

I think COVID-19 has stretched the imagination of Olympic Committee members. Two Olympic Games have gone ahead without fans in the stands. That shrinks the need for huge stadiums with every successive tournament. If they were to shrink the number of seating and fan tickets they expect to sell at these kinds of events, we could go to smaller mountain towns with smaller facilities. Athletes would compete in front of their family and friends, and some locals, and the media of course, but there would be no need for huge spectator facilities.

This would reduce international travel around the Games, which is a big contributor to the overall environmental footprint, and would open up opportunities for smaller cities with smaller venues to host.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Madeleine Orr does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.