Five weeks after Lisa Khan jetted off on a family holiday to Europe, she received a surprise text from a stranger.

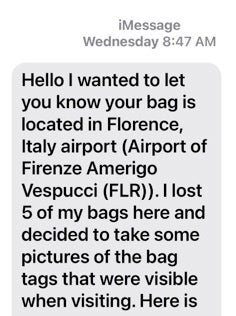

“Hello, I wanted to let you know your bag is located in Florence, Italy Airport (Airport of Firenze Amerigo Vespucci, FLR). I lost five of my bags here and decided to take some pictures of the bag tags that were visible when visiting,” the message read.

Ms Khan had never even travelled to the Italian city.

But there her bag was among a vast pile of lost luggage, each item having become separated from its owner somewhere along the journey.

Speaking from her home in Florida, Ms Khan tells The Independent the saga all began on 30 June, when her family of four headed off on what was to be their last big trip together before her son went to college.

They had booked with Lufthansa to fly from Orlando to Rome, with a connecting flight in Frankfurt, Germany.

From Rome, they were going on a two-night stay in Tuscany, followed by a six-night cruise around the Mediterranean.

When they arrived at Orlando International Airport, Ms Khan, her husband, son and daughter each checked in a suitcase.

Their flight to Frankfurt was delayed, meaning they would miss their connecting flight to Rome, so they were switched to a flight to Florence. However, that flight was also cancelled.

Ultimately, the family ended up being booked on to a different flight to Rome with Lufthansa subsidiary Air Dolomiti.

But while the family continued the journey to their end destination, it seems their luggage did not.

“They told us ‘Yes, we’ll make sure your bags are there,’” says Ms Khan.

“We took the flight to Rome and when we were waiting at the baggage carousel there, none of our bags showed up.”

A 63-day journey

Over the next two months – and thanks to hours of phone calls, airport visits and persistence from Ms Khan’s husband – the four bags finally made their way back to the Khans, one by one.

First came her son’s bag, which arrived one day before the cruise – leaving the other three family members to spend their entire eight-day vacation and return home to Florida still minus their belongings.

About a week after they arrived back home, the bag belonging to Ms Khan’s daughter showed up in Orlando.

Several more weeks passed then Ms Khan received that surprise message from a stranger on 10 August.

“I woke up to this text from a number I didn’t recognise. A lady in Florence said she was looking for her own bag and found mine. She then said ‘Oh, I’ve found a second one of yours,’” she says.

“I was jumping up and down.”

Finally, having located the last two bags, her husband considered flying to Florence in person to collect them, for fear something else would go wrong.

In the end, he managed to work with an agent at Air Dolomiti, who said she would get the family’s bags to them.

So, the suitcases continued on their European tour, being booked on to a plane from Florence to Munich.

But the saga wasn’t over yet.

While her husband’s bag landed in Washington Dulles airport from Munich, Ms Khan’s bag failed to arrive.

Finally, on the night of 31 August, she got a call to say her bag had arrived and was waiting for her at Orlando airport.

“It was 63 days in total from when we left for our vacation to when we got the last bag back,” says Ms Khan.

“We flew from Orlando to Rome on 30 June and that was the last time we saw my bag until 31 August.”

The Khan family is far from alone in their plight.

Summer of lost luggage

As holidaymakers have taken to the sky once again, following two years of pandemic-related travel slowdown, lost and delayed luggage appears to have become the norm.

More than six bags in every 1,000 pieces of luggage checked in by passengers in July 2022 were at least temporarily lost, according to the most recent data from the US Department of Transportation.

The number of delayed or lost bags rose to 0.64 per cent that month, up from 0.59 per cent in the same month in 2021.

During one especially memorable incident at London’s Heathrow Airport in June, thousands of suitcases and bags were pictured piled sky-high outside a terminal, in what was infamously dubbed “baggage mountain”.

That particular issue, at the world’s seventh busiest airport, all started with a technical glitch in the baggage system at Terminal 2. This then resulted in a huge backlog of luggage stuck in transit, leaving baggage handlers overwhelmed while trying to sort them out.

The Independent exclusively reported how Heathrow responded by asking airlines to cancel 10 per cent of their flights one day that month, so the transport hub could tackle the burgeoning problem. A staggering 15,000 passengers across 90 flights were estimated to be affected by the grounding of planes that day.

It was a meltdown that sparked an executive at Emirates to accuse the London airport of creating an “airmageddon”.

Meanwhile, Delta took action by flying a plane (from London to Detroit) containing zero passengers but 1,000 lost bags, in an effort to help reunite customers with their missing luggage.

Unsurprisingly, lost luggage complaints have been skyrocketing, with baggage being the number one cause of air travel complaints in July 2022.

A staggering 1,842 complaints were lodged that month, more than eight times the 227 complaints received in July 2021, DOT data shows.

Such has been the chaos, the 2022 peak travel season earned the unfavourable nickname “the summer of lost luggage”.

“This isn’t new. People have been losing luggage since the beginning of air travel,” Guillermo Ochovo, director of Cargo Facts Consulting, tells The Independent.

But this year reached crisis levels as the airline industry struggled to cope with the sudden surge in demand from travellers, he explains.

More demand, fewer staff

The airline industry was one of the hardest hit when Covid-19 spread across the globe and travel ground to a halt.

With borders closed and travel restrictions rumbling on, thousands of pilots, air stewards, ground handling staff and airport workers were all laid off.

Airlines also terminated or changed contracts with third-party suppliers – such as baggage-handling companies – as neither party was able to provide a service when no passengers were taking to the sky.

Now, travel has returned to almost pre-pandemic levels.

On 21 September, almost 2 million travellers passed through Transportation Security Administration (TSA) checkpoints in the US – more than three times the amount of travellers (roughly 600,000) on the same day in 2020, and close to the 2.2 million travellers on the same date in 2019.

“Airlines have seen a strong surge in booking demand in the summer, and so they’ve rushed to add capacity and sell tickets,” says Mr Ochovo.

“After two years of losing money, airlines have started to see the light, with the lifting of travel restrictions and people wanting to get back to their holidays and travel again.”

While this is good news, Mr Ochovo says the industry wasn’t expecting such a rise in demand so quickly.

“The airlines did not anticipate this level of increased demand and they don’t have the resources in place to meet it,” he says.

“Thousands of people were laid off during the pandemic and so the main cause of the luggage crisis has been the lack of handling and ground staff at airports.”

As Mr Ochovo explains, while airlines have been launching major recruitment drives, baggage-handling companies are still grappling with staff shortages.

“There has been a big disconnection between airlines and their suppliers,” he says.

“Now there’s increased travel demand and not enough resources to meet it, as baggage-handling companies do not have enough staff to deal with problems when they arise.”

‘Complex industrial ballet’

It’s not only a shortage in volume of baggage handlers, but a loss of experience and skillset, says Gaylloyd Dadyala, chairman of the International Association of Baggage System Companies (IABSC).

“By the time demand returned, people who were laid off had gotten other jobs and so the institutional knowledge that these people had had disappeared,” he tells The Independent.

As the industry ramps up hiring, he says it is now “new hands on deck” trying to learn the ropes without having “the experienced hands to teach them the tricks”.

Mr Dadyala describes the baggage-handling system as a complex one that goes on behind the scenes of the passenger’s journey.

“Beneath the levels that the passenger sees is what I call a complex, industrial ballet taking place,” he explains.

“And when the industrial ballet is going to the right tune, things are going very well.

“But when something gets out of kilter that’s where experience comes in.”

Exactly how this “industrial ballet” goes wrong, and how luggage such as Ms Khan’s goes missing, has long been a source of mystery for frustrated passengers who reach their destinations to find their bags didn’t make it.

So, how exactly does the baggage-handling system work?

What happens to your bag after you wave it off at the check-in desk?

At what stage can it all go wrong?

And where does your bag end up when it goes missing?

Behind the scenes of a passenger’s journey, their luggage is embarking on a far-flung journey all on its own.

Behind the scenes of a bag’s journey

It’s a journey that goes through three separate stages from the moment of check-in to the moment of arrival – with each stage adding an additional layer of complexity and opportunities for bags to go missing.

The first stage in the system is when the bag is moved from the check-in desk to the boarding gate.

Second comes the stage when the bag is moved from one gate to another during a transfer.

And the third and final stage is when the bag is moved from the arrival gate to the carousel at the end-destination airport.

During the first stage, the agent registers the luggage with the passenger’s name and travel itinerary at the check-in desk.

Tags and barcodes are printed and attached to the suitcase to connect the passenger and the bag.

Next, the bag is placed on a conveyor belt, and disappears from its owner’s sight.

As the passenger heads to the gate – to perhaps grab a pre-flight drink or a magazine before boarding the plane for take-off – the bag’s adventure really begins.

It passes through an automatic system that scans the bag’s barcodes to allocate it to an area of the baggage-handling conveyor that will send it on a path to the right gate.

Mr Ochovo estimates that around 85 per cent of barcodes are scanned automatically at this stage.

But, for the remainder, the barcode is unreadable, meaning human agents have to scan and sort them manually – opening up the first possibility of human error or delays in reaching the aircraft.

Once a bag has been scanned, a ground handler will then transport it to the gate and load it into the plane.

This is where the labour shortage presents another challenge, as there could be too many bags for the limited number of staff to process in time for take-off.

“If the automatic system isn’t working well or too many bags are not scanned automatically, the ground handler workers may not have enough time to scan them all manually and get them to the right plane on time,” says Mr Ochovo.

If a bag misses its flight, it’s possible it could end up in a country that doesn’t even feature on the passenger’s itinerary, he says.

This can happen when ground handlers place the bag on a new flight, with the aim of getting the luggage to the end destination in the quickest manner.

As airlines prioritise the luggage of passengers on upcoming flights, if the quickest, direct flight is fully booked, the best option may be to put the bags on a plane with a different airline or one that has a connecting flight in another country.

This adds an extra leg of the journey where something could go wrong.

At larger airports, airlines may have a choice of multiple baggage-handling companies they can work with at that hub. Likewise, the baggage handlers at an airport will often be handling luggage for multiple airlines and multiple flights at any given time – further opening up opportunities for bags to be misplaced.

Let’s say the first stage went smoothly and the bag made it onto the same flight as its owner, travelling with them to the next destination but the passenger has a connecting flight to reach their end destination.

Now, this means the bag must also take that connecting flight.

This is where the second stage comes in, as the bag must be transferred from one gate to another.

Mr Ochovo says this adds “another level of complexity”, as it is doubling up the first process – in turn, doubling up the chances of the bag being mishandled.

It’s also likely different baggage-handling companies are operating at each of the airports the bag travels through.

“So, the chance to lose the bag increases,” says Mr Ochovo.

Provided the bag makes it onto the connecting flight, it enters the third and final stage of its journey: baggage collection.

As the bag reaches the end-destination airport, it is time to be reunited with its passenger.

Baggage handlers unload all luggage from the aircraft and place it in an automatic system that scans the barcode again and directs the bag to the correct conveyor belt, so it can be picked up by its owner.

Once again, there could be an issue with the barcode, and ground handlers may have to manually scan the bag.

Staff shortages could again lead to a delay in manually scanning, potentially resulting in the bag missing the limited time slot its flight had been allocated to use the airport conveyor belt. In that scenario, the bag may have reached the same destination as the customer and be in the same building – but they could still be unable to reunite.

At every one of these three stages of a journey, one of the big risks is that the barcode could be lost, damaged or unreadable, explains Mr Ochovo.

And, to further complicate things, the barcodes aren’t universally readable.

“If the bag ends up at the wrong airport and in the hands of the wrong airline, they might not be able to retrieve the information from the barcode,” says Mr Ochovo, pointing out this is – in part – for data protection reasons for passengers.

“The barcodes are not universal but are usually specific to the airline... usually the airport and luggage system can read the final destination but not the passenger information.

“So, that’s why airports are often unable to tell passengers that their bags are there, if it’s in the wrong hands.”

Where does lost luggage go?

If the passenger doesn’t know which airport a bag is at and the airport isn’t able to read the passenger details and contact them, reuniting bag and owner is next to impossible.

Where this lost luggage ultimately ends up is a “difficult question to answer”, says Mr Dadyala.

Airports need to keep their operational space clear, so often there are lost-luggage offices or spaces designated to mishandled bags.

There, so many bags sit unclaimed and gather dust for months and years, leading some airports to hold auctions where buyers can bid for the items.

Ultimately, there is not a lot the passenger can do to prevent their luggage getting lost, says Mr Dadyala.

But he does offer some tips to try to narrow down the chances.

Tips for passengers

“Generally speaking, the challenge is going through a transfer hub,” he says.

Booking a direct flight, or at least avoiding a connecting flight where the transfer window is tight, can help avoid or reduce the risk of losing bags along the way.

Travelling off peak is also a good idea.

“The system and the handlers won’t have as much load at those times, so if there is an interruption to the industrial ballet, the handlers will have a bit more time to deal with it,” he says.

For Ms Khan, she says she will always put a tracking device, Apple’s AirTags, inside her luggage from now on, so she can find out where it is.

While it might not directly ensure the bag reaches its end destination, she says the biggest frustration with her family’s ordeal was that she and the airline “had no clue” where the luggage was.

She placed AirTags inside her cases for a trip to Turkey in September and was able to track them the entire journey – even seeing mid-flight that they were on the same plane as her.

“I think AirTags are a game changer. I wouldn’t travel without them now,” she says.

Given the key role the barcodes play in the chances of luggage being misplaced, Mr Ochovo also urges passengers to ensure they observe the agent placing two barcode stickers on two different places on their bags at the check-in desk.

That said, even though there are many stages where luggage can, and does, go missing within a single journey, he is confident the “summer of lost luggage” is now over.

“June and July were really bad months but by August the situation was alleviated more,” he says.

“I think the fall months will now be good for airlines and ground suppliers, as they hire more people, work together and become better prepared for the next peak season at Christmas.”