Entrepreneurs are often told the key to success is to come up with something you crave that is not yet available. Ryan Schreiber, founder and editor of Pitchfork, is certainly proof of the validity of this advice. "When I got on the internet for the first time I realised its potential," says the self-professed music obsessive. "I could see where it was going from a mile away."

At an early age, Schreiber became a fan of indie music, but found there were few online resources. Some of his friends were printing their own fanzines, which they Xeroxed and distributed around his hometown, Minneapolis. "They were getting interviews with bands that I had tremendous respect for and would just love to talk to for 15 minutes," says Schreiber. "The reviews I was reading at the time lacked strong opinions. They were all pretty much reverent. And I thought: 'Where's the honesty?' I knew that if I listened to 100 records I was going to dislike at least 20 of them. Also, a lot of the music that was getting popular at that time was second-wave Nirvana, such as Filter and the Deftones. I didn't feel it was independent music. It didn't come from independent labels." So after graduating from high school, Schreiber started his own online fanzine.

For the first few years hardly anybody paid attention to Pitchfork, says Schreiber. Meanwhile he was working in a record store and did some other odd jobs. The site kept him going as he "didn't really have any prospects in the real world" and loved being able to talk to artists and receive promos.

Around 1997-98, he recruited a few more writers – remunerated with free promo CDs – and the site went from two reviews a day to four ... and kept on growing. Today Pitchfork has around 50 freelance writers worldwide and 20 full-time staff, based in New York and Chicago.

So how do they choose which acts to cover? Schreiber and his staff dig through stacks of promos (he says they can't, and won't, listen to everything), search MySpace, and follow word-of-mouth and message-board recommendations. He is also a big fan of Mary Anne Hobbs (he's "bummed" that she's leaving her job) and Annie Mac.

In the US, commercial radio has six genre formats, and artists that don't fall into these categories have to find other ways of getting heard. Pitchfork provides a vital alternative for many of these acts. "I don't really pay attention to what happens with independent artists in the mainstream," he says. "We care about musicianship and songcraft above anything else. The stuff that stands out to us is the stuff that doesn't sound like everything else we hear. Like James Blake from the UK, who came from dubstep. His music is largely electronic and sampled, but he has a distinctive approach. Some of what we like, from the outside looking in, is quite pretentious – but some of it is straight-up pop that will appeal to everyone. "Whereas many blogs are niche-specific or taste-specific, we try to be comprehensive in terms of the independent music world – even if we don't like it," says Schreiber. "We're very, very frank."

This frankness has been criticised, however, with some claiming that a bad review on the site can have a detrimental effect on an artist's sales (of course, Pitchfork has also helped to break many acts). Schreiber seems unfazed by this. "There have been many instances of artists coming out against (negative) Pitchfork reviews and attacking us. Sometimes it gains favour with their fans and sometimes they say: 'Oh, shut up – it's music criticism. Why don't you grow up'.' It's not as common as I thought it would be. Everybody on the internet is so critical of anybody who steps out of line."

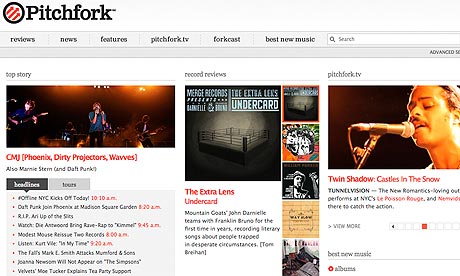

In fact, stepping out of line appears to have worked well for Schreiber: Pitchfork now has more than 2.5 million unique visitors each month and 400,000 visits each day, with many indie music fans seeing the site as one of their primary music references. Not bad going for a 34-year-old music geek with no prospects in the real world.

.png?w=600)