Ever wondered whether you’d have a better chance at winning an Olympic gold if you could fling words rather than a javelin? Or maybe you could beat down your opponents with comedic wit? If so, you may have been a strong contender at the Poetry Olympics, held in Rome around 1700.

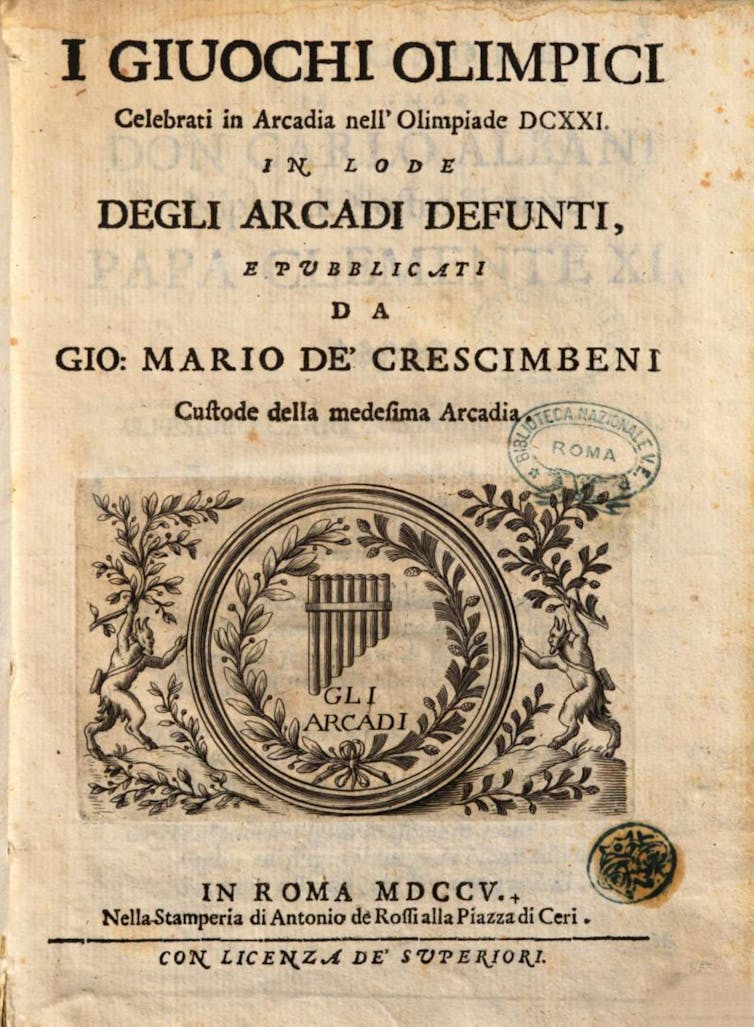

Some 200 years before the modern revival of the Olympics as we now know it, a group of poets met in a garden in Rome to revive the ancient games in their own way. Their Giuochi Olimpici (“Olympic games” in Italian) was based not on speed or strength, but on one’s ability to string together a poem or win a debate.

An ode to the mythical pastoral poets

The first of these new games was held in 1693 and they ran semi-regularly into the mid-18th century. The group met outdoors in places including the Farnese Gardens, a lofty site on the Palatine Hill in Rome overlooking the ruins of the Ancient Forum.

They was a mix of (mostly male) poets, writers, lawyers, clergymen, nobles, artists and musicians. All were members of the Arcadian Academy, a group named for the region of ancient Greece – Arcadia – that was regarded as the “home of poetry” in Early Modern Europe.

In 1504, the writer Jacopo Sannazaro had published a poem called Arcadia that presented an ideal vision of a world in which shepherds lived in harmony with nature.

This idea took hold of writers and artists, who came to view such an idyllic landscape as a necessity for poetic invention. They imagined shepherds and shepherdesses roaming with their flocks and conversing in poetry with nymphs and satyrs – an image that was further popularised in 17th-century paintings by Nicholas Poussin and Claude Lorrain.

These later 17th-century writers longed to inhabit this world of mythical pastoral poets. When they met, they cast aside their real names to use pseudonyms as shepherds or shepherdesses. They pretended the garden they met in was an Arcadian wood. The garden they built in Rome is still called “Bosco Parrasio” or Parrhasian Wood (Parrhasia was a region in ancient Arcadia).

They described their meetings as “democratic” gatherings, which was highly unusual in Rome at the time, as all aspects of daily life were governed by social hierarchies and strict etiquette. But the naturalistic setting of the gardens and the playful disguises as shepherds or shepherdesses allowed for a bending of the rules.

It was in this setting the poetic revival of the Olympic games took place. It was one of a few revivals in 17th-century Europe, with several sporting competitions in England also calling themselves “Olympicks” or “Olympiads”. But the Olympics in Rome was the first to focus only on poetic and literary performance.

Later on, poetry also became an official part of the first of the modern Olympic games – and remained so until 1948.

Intellectual combat

The Poetry Olympics took the ancient pentathlon, but replaced the five sporting competitions with five new games based on poetic composition and intellectual debate. A description from 1701 lists these as “the foot race, the javelin, the discus, the wrestling and the long jump”. Each was intended to showcase skill in poetry, wit or song.

The foot race became a game called “the oracle”, in which a debate was held on a topic set by the custodian of the games. The javelin became a game of dispute, in which the “shepherds” took part in friendly poetic disagreements. They were encouraged “to sting and prick each other with verses” to dispel any “bitterness that may have occupied their minds”.

The third game, the discus, became a game of wits in which the poets bested each other in composing witty songs.

Wrestling changed to a “game of transformation”, drawing from the myth of the metamorphosis of the ancient Arcadian King Lycaon, who was transformed into a wolf by Zeus after he sacrificed his son (one origin of the werewolf myth).

The poets presented sonnets about transforming into inferior things such as animals and plants, and then considered the virtues of these new states. In one poem that was recorded in one of the short books published after the event, a competitor imagines becoming an industrious bee, going from petal to petal and creating sweet honey to help them bear the “bitterness of the world”.

In the fifth game, called “the garland”, the winner was the person who could weave together the most beautiful poem in praise of nature. This was the only game in which women could compete.

While this may seem exclusionary, it was actually very permissive for Rome around 1700. Most women at the time received less education and were expected to live relatively cloistered lives. The more relaxed social structure of the academy and the games allowed women to participate in poetic performances and socialise beyond their immediate households.

A way to build bridges

The 300-year-old gathering of poets in a garden in Rome might seem very distant from athletes converging in Paris for the 2024 Olympics, but we can draw some parallels.

Structured play, with its clear rules of engagement, is often regarded as a way of mimicking more serious types of social confrontation. The “play” of games at the Olympics – whether poetic or physical – allows all of us (spectators included) a chance to move through the emotions of combat, disagreement, disappointment and elation in a friendly way.

Gathering for play also encourages us to envision new and better ways to come together as people. Roman poets in 1700 used wit and metaphor to push against the limits of courtly society. In 2024, leaders can point to the Paris Olympics and ask us to imagine a world that comes together in friendly competition, rather than conflict and disagreement.

Katrina Grant does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.