In his most intimate moments of mourning, when no one but ghosts were watching, Gabriel Taylor would bring his big brother back to life. It’s a ritual that started when he was 9 years old. He would put on the football helmet and scowl behind its rainbow-tinted visor, stalking from room to room like the floor was a defensive backfield. He would sneer through its gold facemask, barking trash talk across an invisible line of scrimmage. He would slap its burgundy shell, crouch into a ready stance and wiggle his fingers, eager to pounce. “Just walking around the house, acting like him,” Gabriel says. “Getting into that mode, that mindset . . . where he did his thing.”

Almost 15 years have passed since Sean Taylor was killed by a burglar at age 24, on Nov. 27, 2007, in the middle of his fourth NFL season with Washington. In that time, his little brother has never shied away from the shadow Sean left behind. Growing up, Gabriel played on a Miami-area youth football team that honored Sean by putting his name on the back of every player’s jersey. In high school, at nearby Gulliver Prep, he competed on Sean Taylor Memorial Field. And today, as a third-year sophomore at Rice, he proudly wears Sean’s college number, 26, while manning the same safety position.

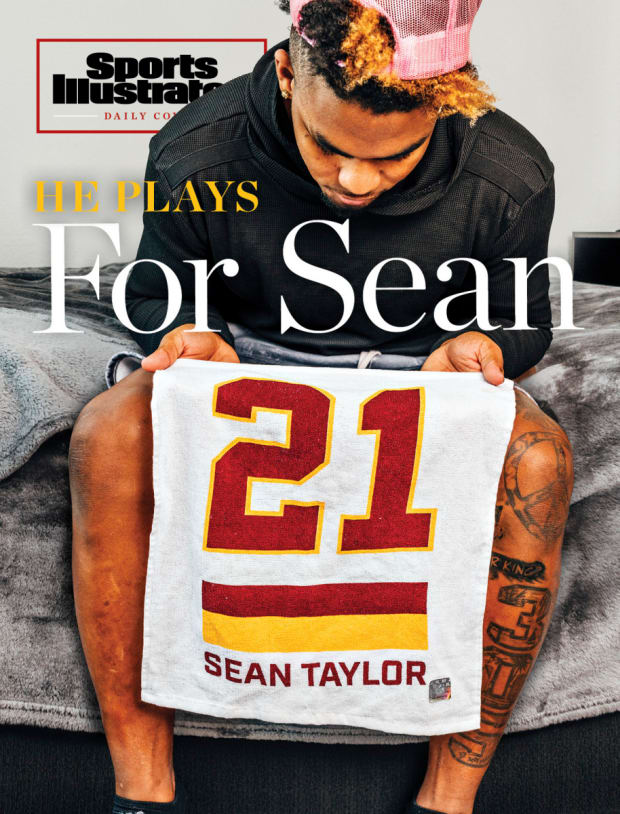

Gabriel keeps his late brother close to him on campus in Houston: He sleeps with a souvenir towel hanging over his headboard, from the day Washington retired Sean’s jersey, and before departing for every game he taps a decal of Sean’s smiling face on the wall. “Then I do this,” the younger Taylor says, curling his thumb and ring fingers while straightening the other three to form Sean’s NFL number, 21. “Then I walk out.”

Arturo Olmos/Sports Illustrated

Visiting his parents in South Florida means paying tribute at the shrine of memorabilia on permanent display. There are trophies, medals and footballs cluttering multiple bookshelves; grass-stained uniforms behind glass frames; and at least one of Sean’s durags. Still, no item connects the 21-year-old Gabriel with his brother’s legacy quite like the game-used Washington helmet. The chinstrap became tougher to buckle as puberty hit. (“My head’s too big,” Gabriel says.) But the private ritual of wearing it continued apace through his adolescence, until he left for college. “Knowing that I have that,” he says, “it means a lot.”

Part of the reason is that wearing it helps him tap into who Sean was as a player: a tireless worker, a top-notch talent, a downhill force with a devil-may-care style that put the fear of God into ballcarriers. It also reminds Gabriel of the player Sean believed his little brother would become.

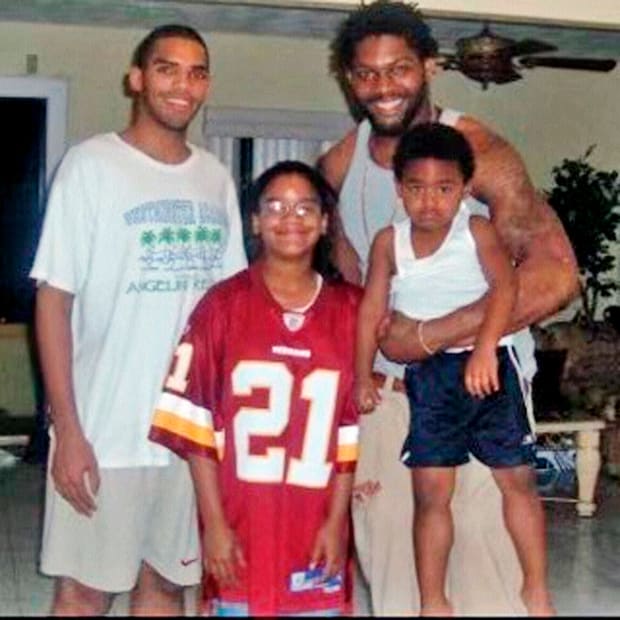

Gabriel was born on Sept. 27, 2001, the same Thursday that Sean—then a true freshman at Miami, starting on special teams for his hometown team—made a trio of tackles in a road win over Pittsburgh. Despite the 18-year age gap between the brothers (who share a father, Pete Taylor, and have different mothers), an instantaneous bond was formed. “The first time Sean held Gabe, he cradled him like a football and was like, ‘Oh my God, am I doing it right?’ ” says Gabriel’s mother, Simone Taylor. “I remember [Sean] looking at him and thinking he was so cute.”

It wasn’t long before Gabriel begged to tag along with Sean and Pete on their famous guerilla workouts. So he would sprint next to Sean on highway shoulders, lug tires at bus depots and run ladders through the sands of West Palm Beach. His first tackle football game came at age 4, against opponents two years older. “He always knew that’s what he wanted to do,” Simone says.

Early on, Gabriel couldn’t pronounce Sean’s name, instead calling him “Ton.” It was also a good metric for how much he idolized his brother. After Washington drafted Sean with the fifth pick of the 2004 draft, Pete and Simone bought Gabriel a child-sized burgundy helmet, shoulder pads, a No. 21 T-shirt and a pair of cleats. “He’d wear that whole outfit and run around, tackling everything and everyone,” Simone says.

Sean, in his day, was a defensive back with a rare blend of size and speed, his play earning him NFL All-Decade honors. But he was best known for his full-throated physicality. And, often, Gabriel was adamant about embracing that style; one time Simone returned home to find Gabriel bleeding from a sizable cut after crashing through a glass table. Simone says, “He was like, ‘Don’t worry; I was trying to tackle the couch cushions and I hit my head, but I’m fine!’ ”

A reclusive type who gave few interviews, Sean betrayed little to the public beyond a hard-edged exterior that occasionally went over the line. (See: his second-half ejection from a January 2006 playoff game against the Buccaneers for spitting in running back Michael Pittman’s face.) Those close to him, however, recall a tender side, especially when it came to his brother. “He loved Gabriel because he was looking at his Mini-Me,” Simone says. Asked what memories are sharp from their time together, Gabriel replies, “Of course, workouts. Video games. And this Easter party, I was running around playing hide-and-go-seek, and all of a sudden, someone dunks a ball on this hoop, and it starts to come down on me. And the first person who ran to catch it was Sean. He saved me. I’ll never forget that.”

Scott Cunningham/Getty Images

Gabriel attended most of Sean’s pro games, Simone says, notably that 2006 wild-card contest at Tampa Bay when, in the first half, Sean recovered a fumble for a touchdown and handed it to Gabriel in the stands. “It was like he was passing that baton,” Simone says. Thanks to his busy in-season schedule, Sean wasn’t able to watch Gabriel play much in person. But he evidently saw enough promise at their workouts with Pete to make a bold prediction, telling Simone once, “Gabriel’s gonna be great, because when I was his age, I was so uncoordinated; I couldn’t do the same things he’s doing. For real, he’s just different.”

“He saw something in me that I never saw,” Gabriel says. “But he never told me that before he passed away.”

One Sunday morning when Gabriel was almost 7, the bleary-eyed boy appeared in the door frame of his mother’s bedroom with a coloring book and a heavy heart.

This was the summer of 2008, nine months after Sean died from gunshot wounds suffered during a late-night burglary attempt at his home in the Miami suburb of Palmetto Bay, where he was visiting his fiancé, Jackie García, and his baby daughter, Jackie.

“I wish Sean was here,” Simone recalls Gabriel saying as he climbed into her bed and began to draw. “Because if he was here, I could’ve been the artist and he could’ve been the baller.”

“You can still be an artist,” Simone countered. “Sean would’ve wanted you to be whatever you wanted.”

“No, Mommy; you don’t understand,” Gabriel replied. “When I’m running, I feel him running with me. When I hit, I feel him in my chest. When I catch, I feel him in my arms. Sean wants me to be great.”

Courtesy of the Taylor Family

As with everyone close to Sean, his death required a degree of processing. “I remember looking around at the funeral, wondering why everyone was crying,” Gabriel says. “I didn’t understand death.” But when reality eventually hit, it landed with brute force. Simone remembers it distinctly: “Gabriel was on the laptop,” she says. “All of a sudden I heard him start bawling, and he was pointing to the screen. He was [watching] some of Sean’s highlights. And he was realizing that his brother wasn’t coming back.”

Soon enough, though, Gabriel was sprinting toward Sean’s dream for him. By his 10th birthday he was already well versed in football film study, regularly requesting that his parents tape his Pop Warner games so he could pore over the footage; in middle school he once drew the ire of an especially stern teacher by retreating to the back of the classroom to crank out push-ups after having finished his assignment. “He’d wake up early in the morning,” Simone remembers, “and say that if he’s not working, some other little kid is getting better than him.”

That effort paid off in part when Gabriel was named one of five finalists for the 2014 SI Kids SportsKid of the Year award, having scored 13 touchdowns on 900 total yards as a running back while breaking up 10 passes as a defensive back in six games. As SI Kids noted at the time, “[Gabriel] says he honors his big brother by ‘staying focused and giving my all on the field.’ ”

Years later, in the course of getting to know Gabriel, Rice assistant coach Cedric Calhoun would reach a similar conclusion. Eventually. In 2019, Calhoun, whose recruiting territory includes Sean’s old Miami turf, was scouting at Gulliver Prep when talk turned to the namesake of the school’s stadium, Sean Taylor Memorial Field. Recalls Calhoun: “The coach [Earl Sims] is a really good friend, and he goes, ‘Hey, Ced, I want to show you something.’ He puts on some tape. After three or four plays, he pauses it and goes, ‘That’s Sean’s brother.’ I said, ‘Hell naw, are you serious? Sean has a brother?!’ ”

Gabriel, a three-star recruit, had flown under the radar in part because he was on the small side for a safety—today he’s listed at 5' 10" and 190 pounds, compared to Sean’s 6' 2", 212. More than that, though: He stopped playing football for three years to focus on what he considered his best sport, basketball. (He was nominated for the 2020 McDonald’s All-American game and recorded a quadruple double in one game during his final season.)

Gabriel always knew, though, that he’d return to football, and when he suited up for Gulliver as a senior he returned five of his 10 interceptions for touchdowns. His motivations were crystallized for Calhoun when the assistant returned to Miami for an official home visit. Calhoun, who lived two miles from Sean’s old house in Palmetto Bay when the safety was killed, knew Sean’s story well by then, and “just seeing the shrine they had for Sean,” he says, “that was enough.”

“He plays in [Sean’s] memory. He walks this life representing his family and his brother, no doubt.”

What the heck is the Jim Thorpe Award?

The question was gnawing at Gabriel last October, coming off a career performance—10 tackles, a forced fumble and a pass breakup in a big win over Conference USA foe Alabama-Birmingham—that earned him Jim Thorpe Player of the Week honors as the nation’s best defensive back. Sharing the news with his parents over the phone, Gabriel listened with awe as Pete explained that as a junior at Miami, Sean himself had been named a finalist for the season-long version of the Jim Thorpe Award . . . but that he ultimately finished second (behind Oklahoma’s Derrick Strait). A year later, considering which football accomplishments most make him feel like he’s living up to Sean’s legacy, Gabriel cites this moment first.

That honor also marked a turning point after a stormy start to his college career, beginning with four weeks of isolation in summer 2020 due to a positive COVID-19 test. Secluded in a dorm room, with barely any natural light and with meals dropped outside his door, Gabriel says he shed upward of 20 pounds—and a bit of his drive. “I had time to sit and think, Dang, what am I even doing here?” he says. And similar doubts haunted him throughout that pandemic-stunted season, in which he recorded just five total tackles in Rice’s five games, while his parents watched all of them from the stands. “I had to get serious and mature up,” he says. “I couldn’t have [my parents] coming and I’m doing nothing on the field.”

Courtesy of Rice Athletics

Here again he channeled Sean, willing himself to work out three times a day before he reported to training camp for his second season at Rice. Fitting, then, that Gabriel’s breakout, against UAB, came on the heels of an intensely emotional week of tribute.

It started the previous Saturday, after a road shutout loss to Texas–San Antonio, when Gabriel and his parents drove an hour up Interstate 10, napped for an hour at a hotel and eventually caught a red-eye flight that landed in Washington around 6 a.m. From there the family was chauffeured straight to FedExField for the retirement of Sean’s No. 21 jersey.

Nothing could taint that celebration. Not the sleep deprivation. Not the fact that Washington hadn’t bothered to tell the Taylors about the ceremony until four days before. (Team officials later apologized.) Snapping pictures with fans that afternoon, signing autographs, basking in the sea of burgundy 21 jerseys, “It all felt like home,” Gabriel says.

Jetting back to Houston that same night, Gabriel made it back for Monday’s practice and soon learned that he would be making his first collegiate start that Saturday, against UAB. “And he balled out,” safeties coach Colin Spencer says, pointing to “one of the best forced fumbles I’ve ever seen,” in which the safety missed an open-field tackle yet still managed to chase down the ballcarrier and punch the football free. Defensive coordinator Brian Smith, meanwhile, cites another sequence that “looked like he was shot from a cannon” as Gabriel’s high mark of the game, charging from the secondary to make a stop near the line of scrimmage.

But no single play has defined where Gabriel is headed more than a victory-clinching interception that he snared against Louisiana Tech a month later, on the 14th anniversary of Sean’s death. Before that game Gabriel had been uncommonly quiet, retreating to his locker to ruminate with a towel draped over his head. But when the pick settled in his hands he dropped to the ground and burst into tears. “I just felt like I couldn’t lose,” Gabriel says. “Like it was all happening.”

In early August, over lunch at a favorite off-campus poke bowl spot, Gabriel opens the YouTube app on his phone and enters a familiar search: “Sean Taylor highlights.” Scrolling through the results, he finds an hourlong compilation of his brother’s college clips that he estimates he has seen 50 times and a shorter one from Sean’s rookie season, to which he has contributed 60 of its nearly 600,000 views. Then he comes across another, titled “Sean Taylor—Gone But Not Forgotten.”

“I can’t finish this one,” Gabriel says. “The music comes, and I blank out, and then I start crying.”

Arturo Olmos/Sports Illustrated

He mostly watches to stir the memories but also to glean some tips. Gabriel’s basketball background has helped in certain respects on the gridiron—specifically, natural man-to-man coverage skills that have allowed Smith to deploy him in a hybrid nickel role against an opponent’s best slot receiver—and his tackling took a big leap forward in 2021 after a so-so freshman season, coaches say. But the biggest things still missing from his toolbox are lateral speed between the hash marks and, most importantly, Sean’s calling card: a destructive downhill mentality. “It’s how he played, like he had no fear on the field,” Gabriel says. “And he’s gonna let you know that he’s there.”

But football’s culture has also changed, in large part as a response to increased player safety concerns from the type of hits that Sean used to dole out. (Of Sean’s bone-crushing hit on a punter at the 2007 Pro Bowl, Gabriel says: “Nah, you can’t do that no more. It’s two-hand touch now.”) So Gabriel huddles several times each week with Spencer, his position coach, poring over tape of the Saints’ Tyrann Mathieu, the Chargers’ Derwin James and other elite DBs. “My instinct is to get the ball. [Sean’s was] more to hit you as hard as he can,” Gabriel says. “So, I’m trying to take everything I can from him—and then bring it into the new generation.”

As that quest continues—a new chapter begins Sept. 3; Rice opens against USC, with new coach Lincoln Riley—a past generation is right by his side: Whereas Sean, as a rookie, once asked his father for help studying film of Randy Moss before facing the Vikings, today Pete has saved the password for Gabriel’s account on the scouting database Hudl so that he can chime in with advice during game weeks. “Our scouting days are Tuesday, so by Monday my dad already knows who’s fast, who’s not, what their tendencies are,” Gabriel says.

And when Gabriel returns to South Florida on break from school, he’s often accompanied by a small flock of fellow Owls who stay at the family house and train under Pete’s supervision, at a nearby gym. “He knows where he wants to go, where he’s headed,” Pete says. “It just reminds me of the other boy.”

No matter what Gabriel accomplishes on his own, he knows that the comparisons and references to Sean, who would have turned 40 next April, will never fully cease. And that not every invocation comes from a positive place. When he was 8, in his first Pop Warner season, Gabriel and his fellow Florida City Razorbacks were outfitted in new gear by the rapper Timbaland, a family friend, including those custom jerseys bearing Sean’s name. “I remember one time I had four touchdowns in the first quarter and a kid was like, ‘You’re gonna die like your brother,’ ” Gabriel says. Flash forward a decade and he shares a screengrab of a recent Instagram message in which a troll referenced Sean, writing, “N---- got shot and that’s why [you’re] tearing yo acl not going pro.”

More than the sporadic hate, though, Gabriel is fueled by the steady love that people continue to carry for his brother and what his memory stands for—another example of which, the family has been told, will come Nov. 27, before a Week 13 matchup against the Falcons, when Washington plans to unveil a “statue of some sort” as part of a ceremony honoring the 15th anniversary of Sean’s death. “If I was a regular kid they’re not gonna refer to Sean,” Gabriel says. “But it’s cool if I’m in a box with him, because [if people compare us] I’m doing something right. . . . Everybody wants to be Sean. So if you was half of Sean, you’ll be great.”

Toni L. Sandys/The Washington Post/Getty Images

True to Sean’s style, Gabriel doesn’t plan to stop short of his target: In addition to helping the Owls secure their first winning record and reach their first bowl game since 2014 this season, the safety’s sights are set on even bigger prizes downfield. “Jim Thorpe [Award], that’s my main goal,” he says. “[And] I want to wear 21 for the Commanders. That would be the cherry on top of the cake.”

But before all that Gabriel has one more thing to do. He wants to buy a set of LED lights for his bedroom, where he will string them above the decal of a smiling Sean so that they spell out a single word: legacy.