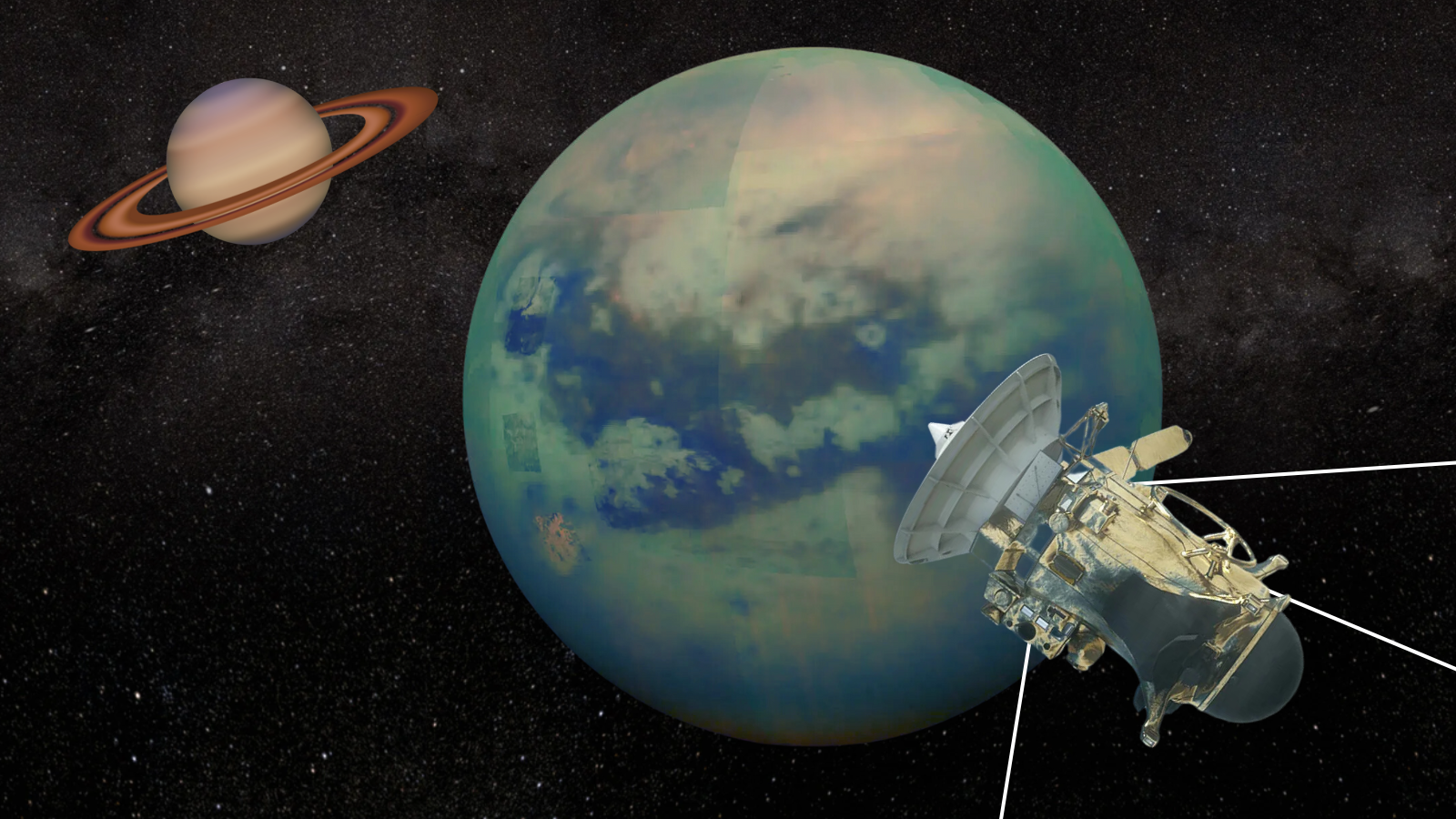

NASA's Cassini-Huygens spacecraft may have dramatically ended its 20-year mission to explore Saturn's neighborhood seven years ago, when it plunged to into the gas giant, but it is still delivering the scientific goods.

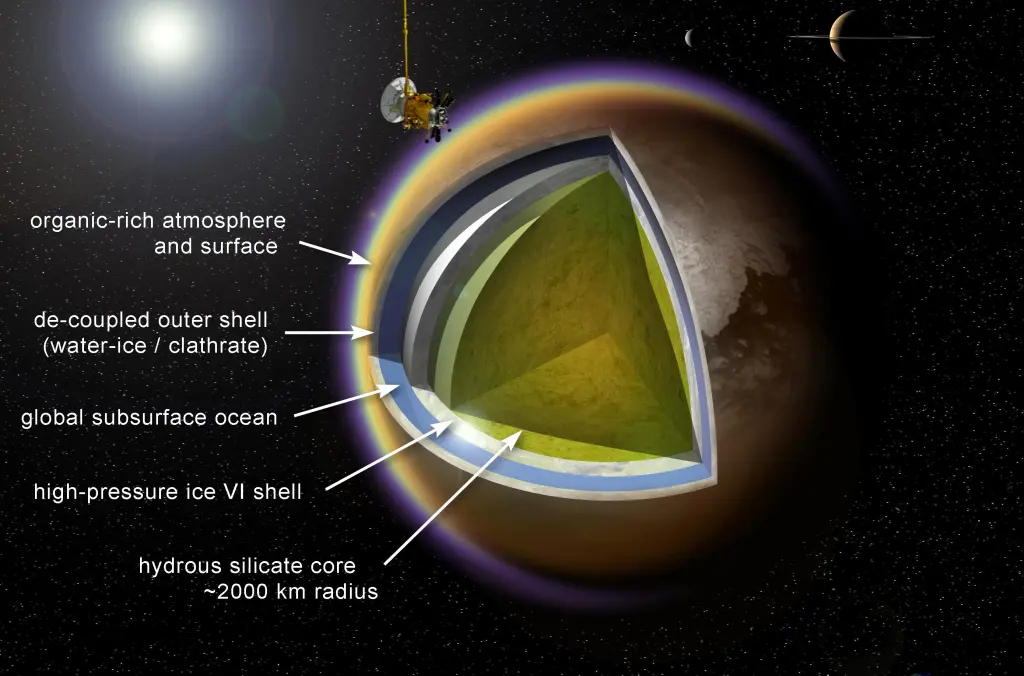

Using radar data collected by Cassini, astronomers from Cornell University have gathered fresh information about the liquid ocean of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, which is comprised of hydrocarbons, a class of organic chemicals made up of carbon and hydrogen. For instance, that class includes chemicals like methane and ethane.

The team was able to analyze the composition and the "roughness" of Titan's sea, which is located near the world's north pole. The researchers found calm seas of methane with a gentle tidal current. Not only is this something that prior examinations of Titan's seas have failed to reveal, but it also lays down a foundation for future investigations into the solar system's ocean moons.

The Cassini data used to make these new findings was collected using "ballistic radar," which involved the spacecraft aiming a radio beam at Titan that was then reflected toward Earth.

Related: Saturn's ocean moon Titan may not be able to support life after all

The effect of this is the polarization of the surface reflection from Titan, which offered views from two different perspectives. Standard radar that saw the signal reflected back to Cassini only offered a single perspective.

"The main difference is that the bistatic information is a more complete dataset and is sensitive to both the composition of the reflecting surface and to its roughness," Valerio Poggiali, team member and a Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science (CCAPS) researcher, said in a statement.

Cassini launched on Oct. 15, 1997, then took seven years to voyage to the Saturnian system. NASA collided Cassini with Saturn in 2017 to prevent the spacecraft from ultimately slamming into one of the gas giant's 146 known moons.

The ballistic radar data used by Poggiali and colleagues was collected by Cassini during four flybys on May 17, June 18 and Oct. 24, 2014, and then again on Nov. 14, 2016. For each of these ballistic radar datasets, the surface reflections were seen as Cassini made its closest approach to Titan, then once again as it moved away from the moon.

The researchers examined observations of three of Titan's polar seas: Kraken Mare, Ligeia Mare, and Punga Mare. They found that the composition of the hydrocarbon seas' surface layers depended on location and latitude. In particular, material at the surface of the southernmost portion of Kraken Mare was the most efficient at reflecting radar signals.

All three of Titan's seas seemed to be calm when Cassini observed them, with the spacecraft seeing waves of around 3.3 millimeters. Where the hydrocarbon seas met the coast, the height of the waves climbed to just 5.2 millimeters, indicating the existence of weak tidal currents.

"We also have indications that the rivers feeding the seas are pure methane until they flow into the open liquid seas, which are more ethane-rich," Poggiali added. "It's like on Earth when fresh-water rivers flow into and mix with the salty water of the oceans."

The team said that this discovery fits with meteorological models of the Saturnian moon, which have predicted that the rain that falls on Titan is mostly methane, with small amounts of ethane and other hydrocarbons.

Poggiali added that the team is continuing to work with data generated by Cassini during its 13 years studying Titan. "There is a mine of data that still waits to be fully analyzed in ways that should yield more discoveries," he concluded. "This is only the first step."

The team's research was published on Tuesday (July 16) in the journal Nature Communications.