When civil rights leaders met at the Roosevelt Hotel in Harlem in early July 1963 to hammer out the ground rules by which they would work together to organise the March on Washington there was really only one main sticking point: Bayard Rustin.

Rustin, a formidable organiser and central figure in the civil rights movement, was a complex and compelling figure. Raised a Quaker, his political development would take him through pacifism, communism, socialism and into the civil rights movement in dramatic fashion. In 1944, after refusing to fight in World War Two, he had been jailed as a conscientious objector. It was primarily through him that the leadership would adopt non-violent direct action not only as a strategy but a principle. "The only weapons we have is our bodies," he once said. "And we have to tuck them in places so wheels don't turn."

Rustin was also openly gay, an attribute which was regarded as a liability in the early sixties in a movement dominated by clerics. His position became particularly vulnerable following his arrest in Pasadena, in 1953, when he was caught having sex with two men in a parked car. Charged with lewd vagrancy he plead out to a lesser 'morals charge' and was sent to jail for 60 days.

Some in the room that day believed all this made him too great a liability to be associated with such a high profile event. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, was candid. "I don't want you leading that march on Washington, because you know I don't give a damn about what they say, but publicly I don't want to have to defend the draft dodging," he said. "I know you're a Quaker, but that's not what I'll have to defend. I'll have to defend draft dodging. I'll have to defend promiscuity. The question is never going to be homosexuality, it's going to be promiscuity and I can't defend that. And the fact is that you were a member of the Young Communist League. And I don't care what you say, I can't defend that."

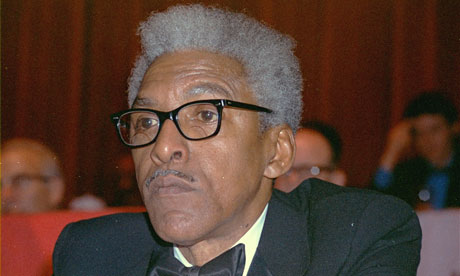

Wilkins did not get his way. Rustin would lead the march and do so brilliantly while Wilkins would be called upon to defend him and do so. Fifty years on the White House has announced that Bayard Rustin will be posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. The award marks the end of a journey for Rustin, who died in 1987: from marginalisation in both life and history to mainstream official accolade just in time for the 50th anniversary of arguably his crowning achievement – organising the march on Washington.

By the time the march was proposed, writes John D'Emilio, author of Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin: "He had recently turned 50. He was still waiting for his day in the limelight, though likely believing it would never come. Prejudice of another sort, still not named as such in mid-century America, had curtailed his opportunities and limited his effectiveness."

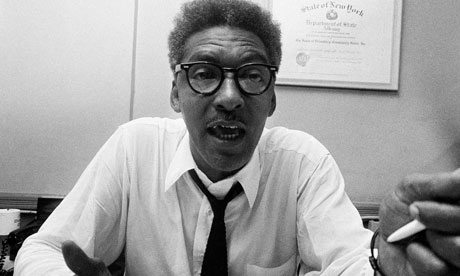

With a vertical mop of salt-and-pepper hair and his tie hung loose on his chest, Rustin always cut a distinctive figure. The idea for a march on Washington had been hatched by his long term mentor, A Philip Randolph, who was 20 years his senior. But there had been few takers from the civil rights movement for a national march until demonstrations erupted in Birmingham in Spring.

Demonstrations in Washington DC are now a common occurrence but what Randolph and Rustin were proposing was audacious – 100,000 protesters descending on the Capitol – unprecedented.

The following eight weeks, writes D'Emilio, "were the busiest in Rustin's life. He had to build an organization out of nothing. He had to assemble a staff and shape them into a team able to perform under intense pressure. He had to craft a coalition that would hang together despite organizational competition, personal animosities and often antagonistic politics. He had to manoeuvre through the mine field of an opposition that ranged from liberals who were counselling moderation to segregationists out to sabotage the event. And he had to do all of this while staying enough out of the public eye so that the liabilities he carried would not undermine his work."

The headquarters for this extraordinary endeavour was a rented, run down former church on West 130th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem. The building soon resembled a cross between a student union in occupation and a military headquarters on high alert. "It was very exciting and frenetic," says Rachelle Horowitz, the march's transport chief who was also Rustin's long-time assistant. "It ran on adrenalin and excitement with everybody working from early in the morning 'til late into the night. It was very collegial, very primitive and very egalitarian."

As such it was a tribute to Rustin's eccentric, hyperactive, and efficient personality. He was in constant motion, interrupting conversations to answer phones even as he passed notes to staff, doodled and chain-smoked. "I had had many differences with Bayard in the past and was destined to have more differences with him in the future," recalled the late civil rights leader James Farmer in his autobiography. "But I must say that I have never seen such a difficult task of coordination performed with more skill and deftness."

Throughout that time as the coalition supporting the march grew, so the nature of the March would change, diluting it of much of its more militant elements even as the prospective size was bolstered. As Rustin announced the abandonment of each new aspect, his young staff would berate him, partly in jest, partly in frustration. "We'd shout: 'Oh Bayard, you're turning it into a circus!'" Horowitz told me with a laugh.

Ever the coalition builder, Rustin explained: "What you have to understand is that the march will succeed if it gets 100,000 people – or 150,000 or 200,000 or more – to show up in Washington. It will be the biggest rally in history. It will show the Black community united as never before – united also with whites from labor and the churches, from all over the country." 250,000 people would ultimately be there.

It was precisely this ability to see the big picture while keeping an eye on details like the number of toilets necessary and the kind of sandwiches people should pack (they advised against using mayonnaise since the heat could spoil it and cause diarrhea) that encouraged Randolph to defend him that day against Wilkin's attacks.

For while Wilkins' manner may have been abrasive, his concerns were routine at the time. Shortly before he died, Farmer explained to me how he vetted people for the Freedom Rides in 1961. "We had to screen them very carefully because we knew that if they found anything to throw at us, they would throw it. We checked for Communists, homosexuals, drug addicts. They had to be 21 or over, and have the approval of their parents. I personally interviewed people, and then would talk to their friends."

When Randolph insisted on Rustin, Wilkins retorted: "You can take that on if you want. But don't expect me to do anything about it when the trouble starts."

The trouble came to a head less than a month before the march when segregationist senator Strom Thurmond took to the Senate floor to brand Rustin a "Communist, draft-dodger and homosexual," entering into the congressional record a picture of Rustin talking to King while King was in a bathtub. But the attack came too late and from too poisoned a well to have any impact beyond rallying support for Rustin even from Wilkins. "I'm sure there were some homophobes in the movement," said activist Eleanor Holmes. "But you knew how to behave when Strom Thurmond attacked."

History turned out to be kinder to Rustin than it was to Thurmond. On Thurmond's death it transpired that the whole time he was railing against integration he had a black daughter by a family maid. Rustin, meanwhile, will now be honoured at a time when gay equality has majority support by a black president in his second term.

"We are a people," wrote Alice Walker in her essay, Zora Neale Hurston: a Cautionary Tale and a Partisan View. "A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children and, if necessary, bone by bone."