The exhibition Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music, currently running at the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, demonstrates that the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which is usually associated with painting, also calls upon other media, including music — the main theme of this exhibition — literature, comic strips, cinema and animation, a much lesser-known aspect of his work.

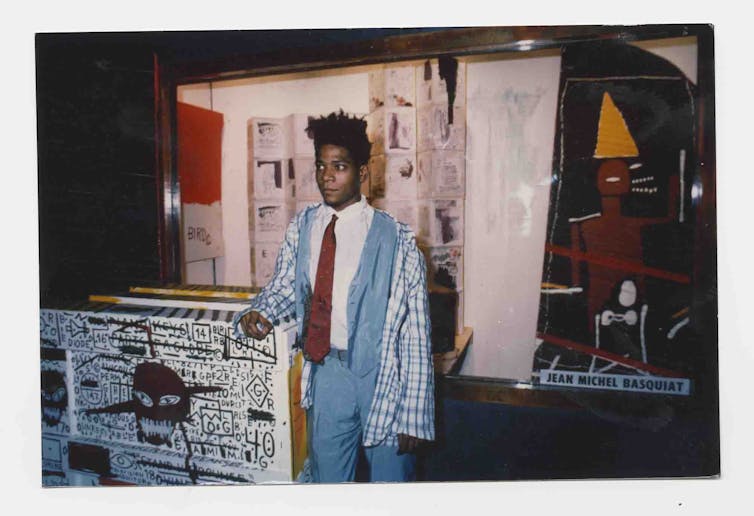

Basquiat was born in New York in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. In the late 1970s, in collaboration with Al Diaz, he drew enigmatic graffiti under the pseudonym SAMO. The artist quickly made a name for himself in the New York art world (becoming friends with Andy Warhol and Madonna, among others). He then produced solo paintings and achieved international fame that continued to grow until his death in 1988.

At the time of the Black Lives Matter movement, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work is more relevant than ever. It highlights racial inequalities and the lack of representation of racialized people in the media, but also the violence suffered by African Americans.

This is what I propose to explore in this article. As a PhD student in literature and performing and screen arts, my research focuses on the interactions between animated film and the visual arts (comics, painting) as well as on the American cartoon.

Love/hate for the cartoon

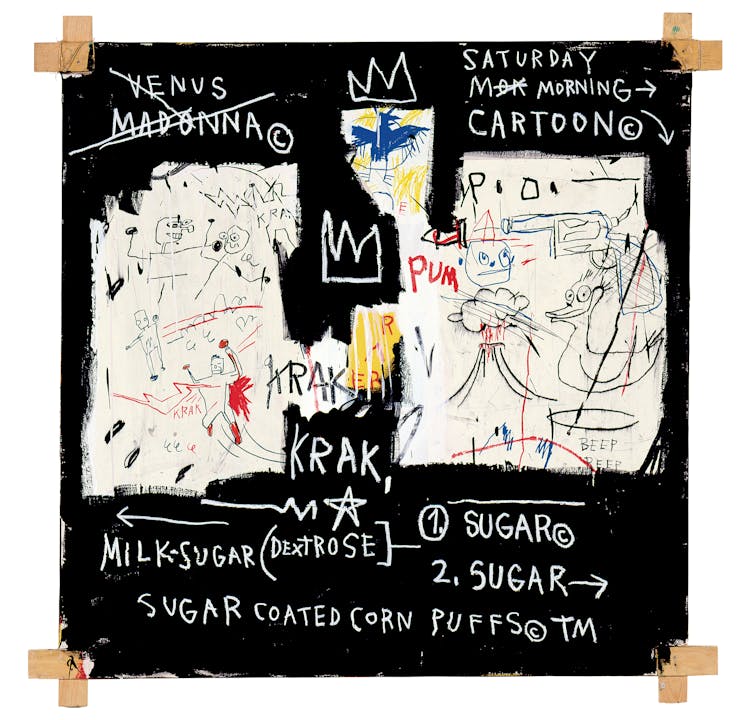

As a child, Basquiat dreamed of becoming a cartoon animator. When he became a painter, the television was always on while he worked in his studio, and regularly ran cartoons. These programmes and films were a great source of inspiration for the artist, who integrated several references to animation and comic strips into his paintings.

One of these works, which can be seen in the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts exhibition, is called Toxic (1984). The painting depicts a Black man with his arms in the air, with a collage in the background that mentions several titles of animated shorts made between 1938 and 1948.

The character is in fact a friend of Basquiat’s, the artist Torrick “Toxic” Ablack. So the title of the painting refers to him. However, knowing that Basquiat played with words and their meanings, “Toxic” could also refer to the relationship he had with the animated films that are mentioned behind the character.

Could we say that the films are considered toxic by Jean-Michel Basquiat, despite his admiration for them? In fact, I think there is a certain duality in this picture: the artist loves the cartoon, but he hates it at the same time. The dictionary definition of the word “toxic” can mean someone or something that likes “to control and influence other people in a dishonest way.” The term therefore implies that the toxic element (the cartoon in this case) is dangerous in a way that isn’t apparent.

The violence of cartoons

The cartoon is often associated with childhood, pleasure, eccentricity.

This is a universe where anything is possible: in Gorilla My Dreams, directed by Robert McKimson in 1948, for example, the character Bugs Bunny talks, dresses up as a baby and imitates a monkey. It appears innocent. However, the cartoon can also represent the worst of humanity in a very sneaky way through the incredible violence it contains: the characters hunt each other, chase each other, hit each other, cut each other, kill each other and then start again.

In Porky’s Hare Hunt, a film directed by Ben Hardaway in 1938 and quoted in Toxic, the character of Porky is injured by dynamite, abused even though he is in his hospital bed and tries to kill a rabbit. Basquiat, who consumed cartoons every day on television, knew that they were a reflection of 20th century American society.

This is an interpretation that could be supported by the title of another of his paintings, which also uses iconography from animation or comics: Television and Cruelty to Animals (1983). This cruelty is also denounced and reproduced in An Opera (1985), which shows Popeye being beaten with the words “ senseless violence ” above his head, as well as in A Panel of Experts (1982), where we see matchstick men hitting each other right next to an enormous revolver.

The violence that Basquiat denounces is so present in the cartoon that it seems, to a certain extent, to have become commonplace, like the violence seen on television newscasts (which he probably watched while he was painting).

Denouncing racial stereotypes

These cartoons are also violent because they often perpetuate racial stereotypes (not to mention the many stereotypes related to sexual orientation, gender, sex, body appearance, etc.).

Bob Clampett’s 1940 film Patient Porky, which is also mentioned in Toxic, features a scene in which a elevator attendant grossly and monstrously parodies a Black character. In Untitled (All Stars) (1983), Basquiat cites Max Fleischer’s 1920 film The Chinaman, which features a highly caricatured Asian character and Koko the Clown putting makeup on to impersonate him.

By placing elements referring to animation in his compositions, Basquiat attempts to denounce a stereotypical and unfair worldview where racialized people are portrayed in an unrealistic way. Basquiat said that if he had not been a painter, he would have been a filmmaker and would have told stories where Black people were portrayed as human beings, not negatively.

So, the title of the painting Toxic carries several meanings. It refers both to the main subject (Torrick “Toxic” Ablack), but also to its relationship to popular culture and to animation, in this case.

The Toxic character has his arms in the air and his hands coloured red. Could it be that this toxic relationship has made his hands dirty? Or, specifically, that the character — because the cartoon has continually portrayed Black people in a pejorative manner — is now being portrayed as a criminal? Indeed, his position indicates that he appears to be under arrest.

This hypothesis is very likely since Basquiat produced several works denouncing police brutality against African Americans, including The Death of Michael Stewart (Defacement) (1983).

Basquiat died prematurely in 1988 at the age of 27. Other artists from the Black community, such as Montréal painters Kezna Dalz, aka Teenadult, Manuel Mathieu, and animation filmmaker Martine Chartrand have, in their own way, taken up his struggle and continue to fight for greater visibility of Black people in the arts.

John Harbour's doctoral research is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.