Water is at the heart of health and well-being for people and nature. Access to it is a human rights issue recognised by international treaties and declarations, and national standards. It’s vital for education and economic productivity. Ultimately, it connects the environment to society.

Th most recent statistics (2020) show a general global trend of positive progress in access to water. The proportion of the global population using safely managed drinking water services increased from 70.2% in 2015 to 74.3% in 2020.

But despite this progress, in 2020, two billion people still lacked safely managed drinking water. The sub-Saharan African region has the largest numbers, with 387 million people still lacking basic drinking water services. Current coverage of access to safe drinking water is estimated at only 54% of the region’s population.

In South Africa, the right to water is enshrined in the constitution. Before the country’s transition to democracy in 1994, government policies were focused on the advancement of the white minority. The development of the country’s water resources wasn’t focused on improving the position of the mostly black, poor majority.

The country has made significant progress since 1996 in expanding water services, especially within the disadvantaged and vulnerable communities and rural areas. But inequality in access to basic services is still a reality. Progress with water supply and sanitation service delivery has been slow and in some instances, it’s deteriorating.

Water is a critical resource. Its provision should be seen as an enabler that facilitates socio-economic development. Water infrastructure needs to be suitably maintained – and upgraded – to ensure water access and reliable supply to guarantee water security.

Progress in South Africa

In 1994, about 14 million people (35%) in South Africa didn’t have basic water supply services. The minimum standard of these services is defined as clean, piped water delivered within 200 metres of a household at a minimum flow rate of 10 litres per minute, for 300 days a year, with any interruption not lasting longer than two days at a time.

The government adopted various policies and programmes aimed at sustainable water development, improving the quantity and the quality of water supply to citizens. This created a comprehensive legislative framework for the provision of water and sanitation services.

The country has made clear progress since 1994 by advancing and extending water supply to rural areas and previously under-serviced areas. During the first decade of democracy (1994 to 2004), an estimated 13.4 million more people had access to basic water supply services.

But the country still faces a great backlog in providing water and sanitation services. While the focus was on water services and backlogs in urban areas over the past few decades, the prevalent and diverse challenges in rural areas were neglected.

Water access reality

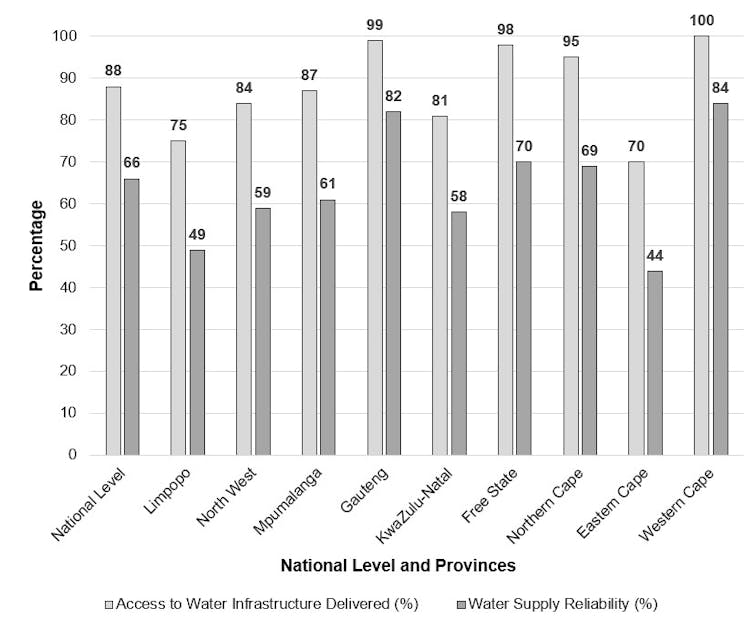

Despite initial progress from 1996, the country’s water situation has deteriorated. The reliability of water services and infrastructure – as shown by frequent water supply interruptions – has been on a downward trend.

It’s important to note that even when communities have access to water through infrastructure, this doesn’t guarantee the delivery of basic water supply services.

Households with access to clean water gradually increasing from 67% in 1993 to an estimated 85% in 2015 and 96% in 2018. On the other hand, the portion of households with reliable and safe water supply services – such as having clean water sources not to far from their household – decreased 64% in 2018.

The deterioration of the country’s water infrastructure and actual delivery of reliable and safe water supply can be attributed to under-investment in infrastructure maintenance and delays in the renewal of old infrastructure. Other contributing factors include poor management, limited budgets, poor revenue management by local municipalities, misappropriation of funds, lack of capacity or necessary technical skills related to water services and sanitation operation and maintenance.

South Africa is thus facing the stark reality of a third of all its water infrastructure not being fully operational. This places it against the global trend of making positive progress.

In addition, the government’s planned budget for fixing or rebuild deteriorated water infrastructure is already R333 billion short of the estimated R898 billion said to be required by the National Water and Sanitation Master Plan published in 2018.

Going forward

Based on my research on integrated water resource management, I propose that South Africa take some of the followings steps to avoid a major water crisis and improve water security. These recommendations are also in the country’s National Water Security Framework.

Address inefficient water use and wastage.

Conduct more research about the impacts of extreme weather events and climate change on the country’s water resources.

Invest in infrastructure maintenance and renewal and address deficient management systems and record-keeping.

Develop and implement an institutional and regulatory framework and ensure compliance with existing regulatory frameworks.

Focus needs to be placed on the current skills deficit. The capacity of key national government departments and municipalities needs to be evaluated in an objective manner.

South Africa needs to move away from simply constructing water supply systems to ensuring that basic levels of service are provided to all.

Anja du Plessis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.