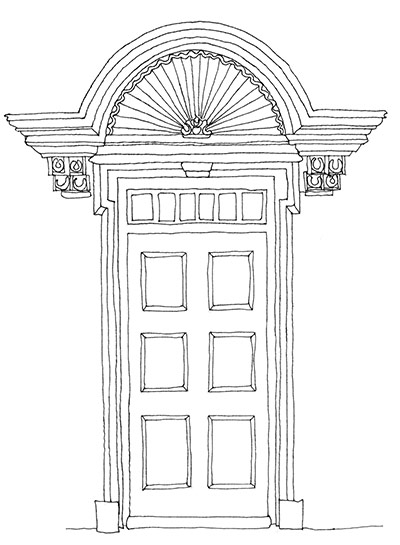

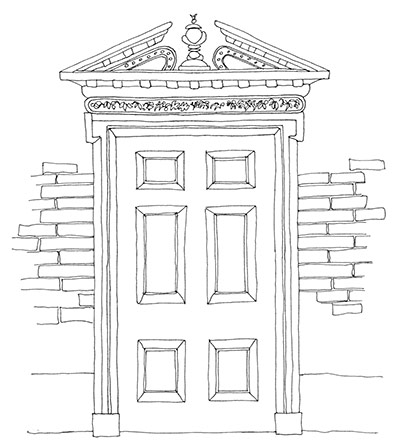

More flamboyant than a mere pediment, but not as practical as a porch, hoods appeared atop doors in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. These were made of wood or stone and supported by narrow brackets. Richly carved, shallow shells were particularly popular at the start of the century. Who cared if you got wet as you waited for the servants to let you in – at least your entrance would be fittingly grand.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

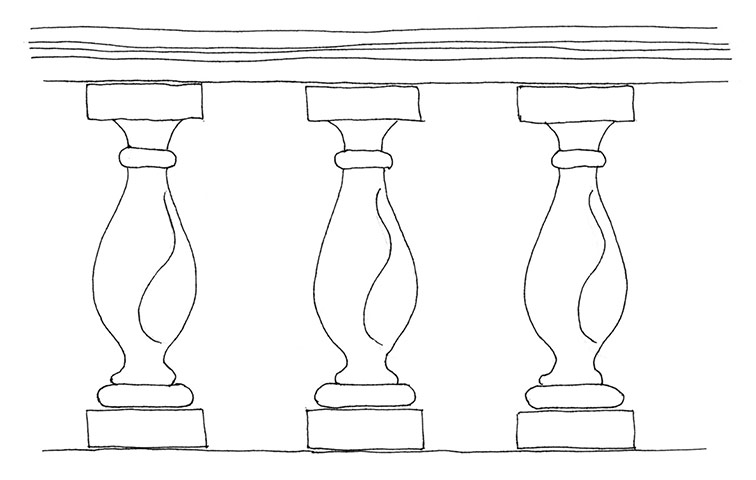

You can usually tell when balusters were made from their shape. The early 17th-century fashion was to have the bulge (the “belly”) near the top, but by around the mid-17th century the belly dropped down the “sleeve” to the bottom so that the baluster became vase-shaped. Twisted balusters also came into vogue after about 1660.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

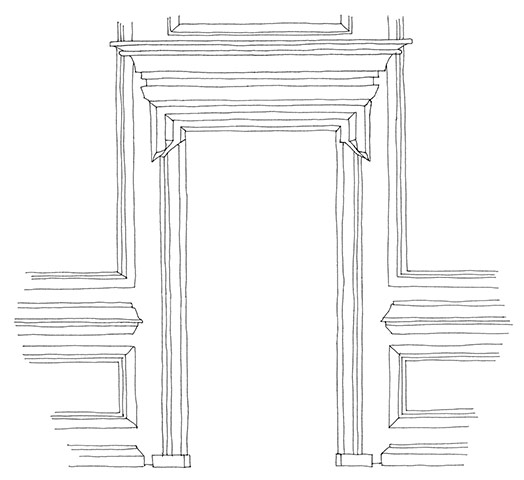

A bold but elegant moulding with a simple profile used to frame openings, concealing joins between surfaces. Commonly seen on wood-panelled walls, doorways, fireplaces and external windows, bolection mouldings are variously made from plaster, wood or stone and (unless part of a style revival) indicate a date around 1700.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

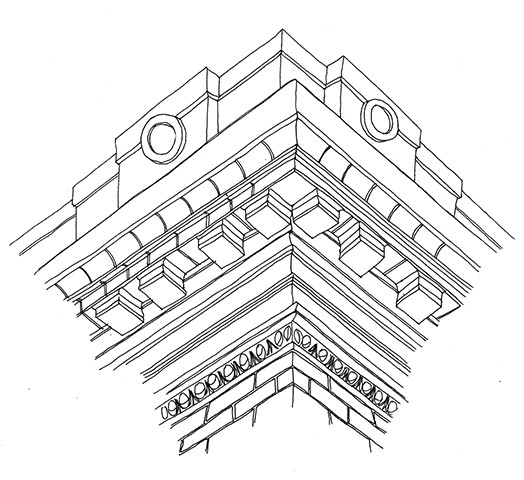

The overhanging roof edge, known as a cornice, was revived by baroque designers from the classical style, but in baroque hands was particularly emboldened. Like much in the period, it was adorned with lavish decoration, such as bold, curved shapes and strong lines, using plaster, stucco or marble. The baroque also placed strong emphasis on the earlier Renaissance feature that is still in use today – the interior cornice, a decorative moulding along the top of the wall where it meets the ceiling.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

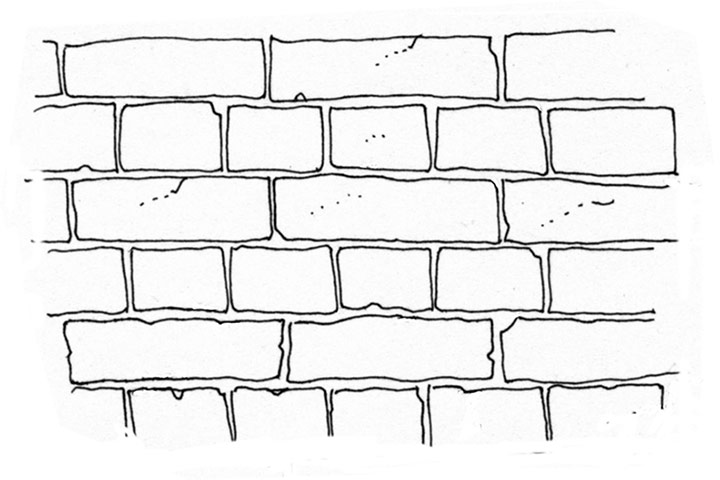

Influenced by the Dutch version of classical architecture, baroque brickies gradually began to ditch the traditional English bond (shown above left) in favour of the more decorative Flemish bond (above right). This was created by alternately laying headers (bricks laid sideways) and stretchers (bricks laid lengthways) in a single course. The next course is laid so that the header lies in the middle of the stretcher in the course below.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

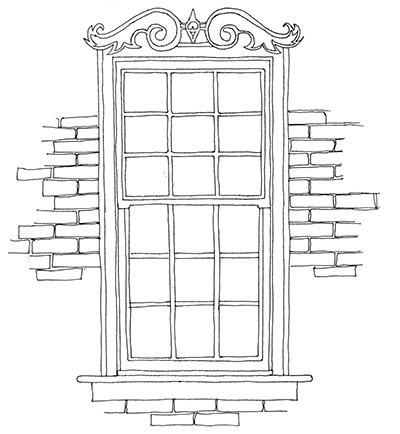

Neat and breezy, sash windows began to replace clumsy casement windows from around 1670. Their flat and symmetrical design allowed inch-by-inch temperature control. In early examples, each sash was divided by chunky glazing bars (measuring up to 5cm x 5cm) into either 9, 12 or 16 separate “lights” and only the bottom sash moved. By the early 19th century, windows had thinner glazing bars and larger panes of glass (typically six “lights” in each sash).

Illustration: Emma Kelly

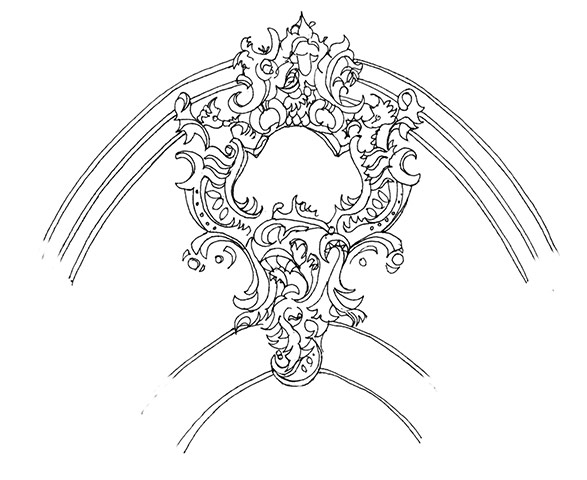

Although primarily considered a style of interior decoration in use in England during the mid-18th century, rococo is sometimes known as the late baroque. Developed in Louis XIV’s France, and more common in mainland Europe (it was known as “the French taste” in this country), it can still be seen on some adornments. Ornate shell forms and fanciful C-shapes are a giveaway.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

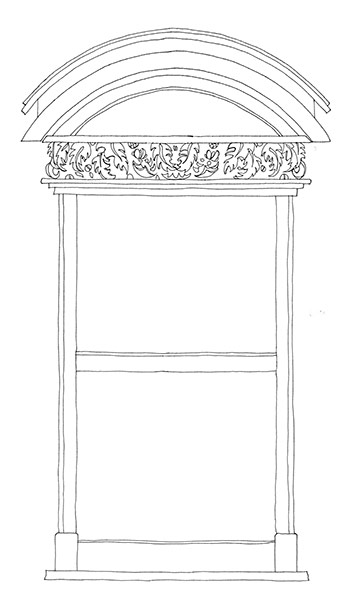

The baroque style allowed for a variety of lavish decoration above windows and doors, but the basic shape of baroque pediment was often curved – a style with its roots in the Renaissance. Also known as a segmental pediment, as it forms part of a circle, like a small arch, these can take both “open” and “broken” forms.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

A broken pediment – either open or broken at the apex – above a facade, door or window, is a recurring motif of the baroque, taken from the late Renaissance period, but with more lavish adornment. The designers would usually decorate the space with a great variety of ornament, such as extravagant statuary, decorative urns or coats of arms.

Illustration: Emma Kelly