Naamcial’s craft beers often have distinctly Thai flavours, as he experiments with the country’s native produce, boiling the pulp of jackfruit and mango to mix into different creations. Yet his homemade products are forbidden in the kingdom.

Talking to the Guardian under a pseudonym, Naamcial says he would like to operate a legal brewery, but Thailand’s laws around alcohol production make this ambition almost impossible for newcomers. Current laws restrict brewing licences to manufacturers that have capital of 10 million baht (£230,000), while brewpubs must produce at least 100,000 litres a year and only serve their beer on their premises. The legislation effectively blocks new, small breweries from opening, and tips the market firmly in favour of two powerful companies – Thai Beverage, which produces Chang beer, and Boon Rawd Brewery, which produces Singha and Leo.

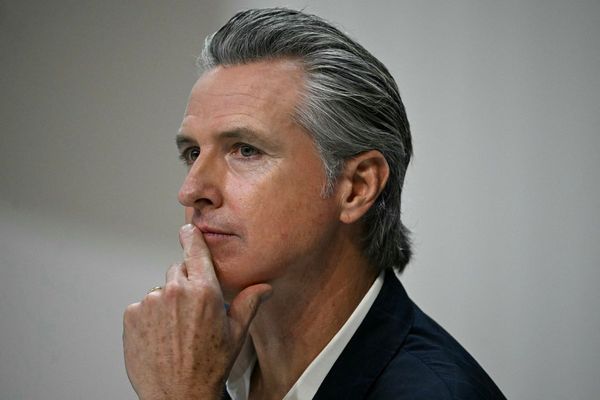

Attempting to loosen these companies’ grip on the Thai beer market, an MP for the opposition Move Forward party, Taopiphop Limjittrakorn, has proposed a new draft law on excise tax, which is under consideration by the Thai cabinet, and which he hopes will make the market accessible to smaller producers.

The law would boost the economy, he says. Furthermore, if passed, the law would mark a symbolic change. “It will let ordinary people do the same business as rich people do.”

In 2017, before he entered politics, Taopiphop was arrested for brewing craft beer at home. He was fined 5,000 baht for brewing illegally without a permit, and a further 500 baht for owning brewing yeast.

For some, craft beer is associated with anti-establishment politics. “It’s very similar to the French Revolution, which started from a cafe in Paris, where people drank coffee,” says Taopiphop. “The fuel of the revolution is not coffee any more, it’s craft beer.” Taopiphop adds that, after the 2014 coup in Thailand, many pro-democracy activists chose to meet in Bangkok’s craft beer bars.

At Bangkok’s Dok Kaew House Bar, a craft beer bar based in a 100-year-old house – which owners say is also inhabited by five ghosts – locals perch at the bar sipping pale ale and cider. Co-owner Nuttapol Sominoi hopes for change. “It’s a monopoly, a closed market, where there is no competition,” he says.

Beside him, a chalkboard lists the various beers on tap, most of which are international. In a fridge lined with cans and glass bottles, there are a few Thai options. One, though, bears a label saying it has been manufactured in Vietnam. Some Thai companies resort to brewing their beers in neighbouring countries and importing them to Thailand to get around the law, though doing so is costly.

A ban on alcohol advertising in Thailand makes business harder still for newcomers. Even sharing a picture of your beer on social media can result in a fine of 50,000 baht if the logo is visible.

“It affects us a lot,” says Supawan Kaewprakob, co-founder of Ther, an all-female brewing project. “We can’t advertise or communicate with our customers about the product at all. We can’t even describe the ingredients or post pictures. It’s illegal, which doesn’t make sense. It clearly blocks small businesses from growing.”

The laws are stifling creativity and the economy, Nuttapol adds, and result in less choice for consumers. It’s particularly galling, given that Thailand offers such advantages for craft brewers. “In western countries they have to use extracts, but we have the fresh ingredients,” he says.

Were the craft beer scene allowed to develop, it would boost agriculture by drawing on local products, and attract tourists to Thailand’s resorts, Nuttapol says.

Bars, along with the tourist sector, have struggled immensely during the pandemic, and face continued restrictions on their operations. Dok Kaew House Bar received no compensation during the pandemic, according to its owners. They are surprised they have managed to stay open.

Supporters of Thailand’s alcohol laws and restrictions on its sales during Covid say such measures are necessary to protect public health.

However, Taopiphop argues that alcohol has been unfairly scapegoated in Thai society, especially during the pandemic. Policy is also influenced by a Buddhist belief that alcohol is sinful, he adds.

If his proposed bill is passed, he hopes it could pave the way to removing laws that stifle entrepreneurship in other industries.

For now, much of Thailand’s craft beer network is operating underground. Naamcial says he is trying to limit his social media presence to avoid attracting attention from the authorities. He finds most of his customers through word of mouth from trusted contacts. It’s normally neighbours who tip off the police, he adds, but his are yet to complain.

He hopes the law will change, but says he’ll continue to brew his beer regardless. He loves the craft of brewing, and the uniqueness of the end result. “[With] my process, and my tools, it’s the only way to make my beer,” he says.