Soon after it began, the double murder trial of defendant and convicted sex offender Russell Bishop decamped from court 16 of London’s Old Bailey to Brighton.

Prosecutor Brian Altman QC swapped wig and gown for flat cap and coat. The jurors were advised to bring a packed lunch and sensible shoes.

Before their excursion, the judge, Mr Justice Sweeney, also told them to pay no attention to a solitary hawthorn tree standing near the entrance of Wild Park, to the north of central Brighton.

In cold hard evidential terms, the tree had nothing to do with the matters at hand. In terms of what the Babes in the Wood case had come to represent, however, it meant everything.

The bare branches of the hawthorn had been enlivened by hanging baskets of flowers and strings of white beads.

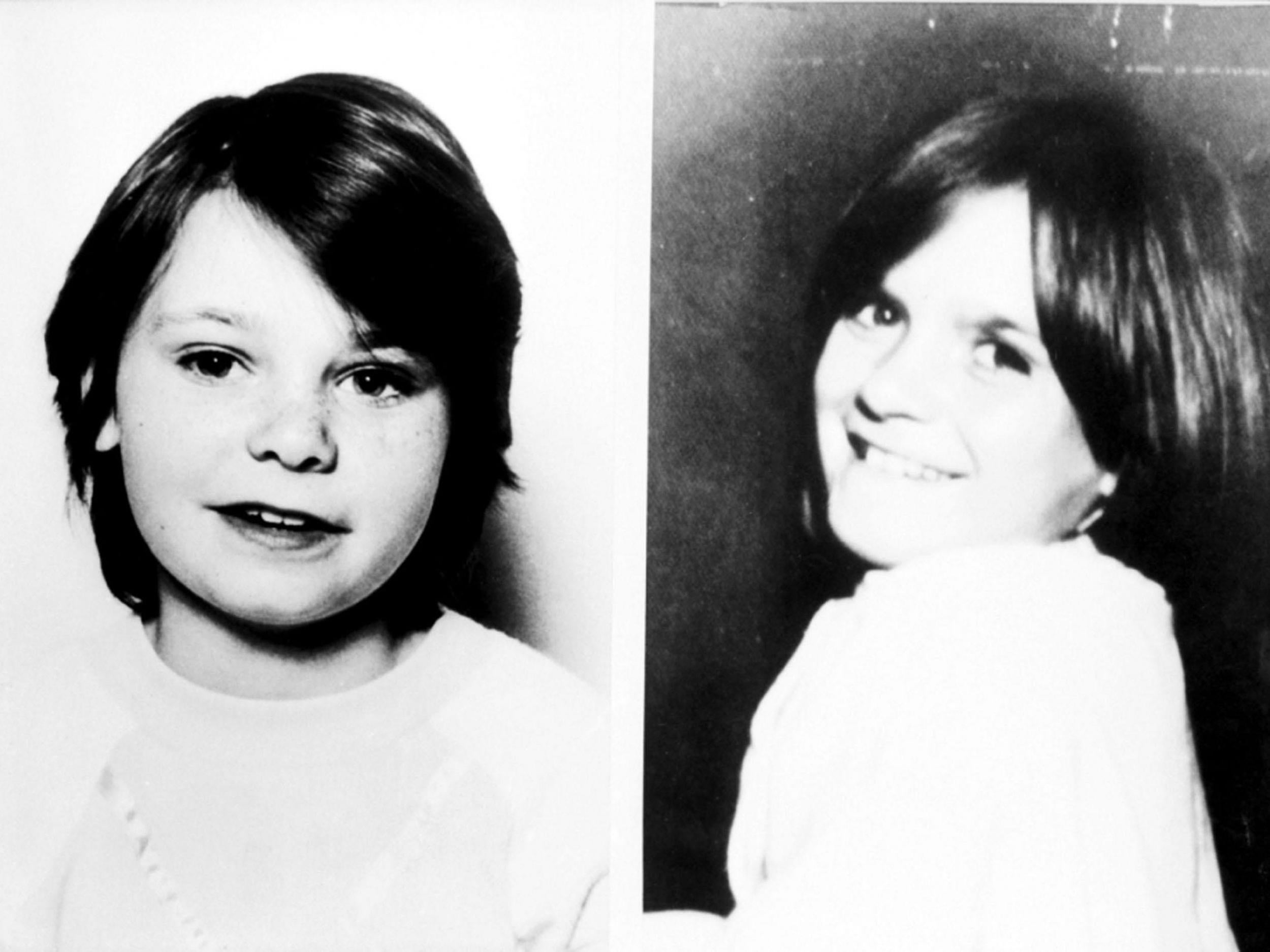

A few yards down the slope, garlanded with flowers, stood a display showing the black and white photographs of two smiling nine-year-old girls.

A pair of pink balloons, swaying in the breeze, spelled out the number 32.

Beside the largest bouquet of flowers was a card addressed “to Nicola and Karen”: “With all our love, both your families. Xxx. Never forgotten, 32 years today.”

On a chalk hill at the start of the South Downs, with the cries of gulls interrupting the rumble of traffic on the Lewes Road, and with the rooftops of the Moulsecoomb housing estate visible beyond, this wasn’t just a memorial to two tragically young murder victims.

For two heartbroken families, for a police force that tried to catch a killer, and for a whole community, this was the manifestation of a scar that for three decades had never been allowed to heal.

The Babes in the Wood

On Thursday 9 October 1986 Karen Hadaway and Nicola Fellows, two friends living three doors away from each other in Moulsecoomb, went out to play after school.

Their bodies were found the following afternoon.

Karen and Nicola lay “icy cold” in a natural den, framed by vegetation, ivy creeping all around, in a hidden corner of Wild Park, reached via a steep climb up a wooded slope.

For those who have had the misfortune of seeing the crime scene photos, the memory is impossible to erase. The eye is drawn to the shocking pink of Nicola’s jumper. Then you notice the grey face of a dead nine-year-old girl.

Karen lay across Nicola, with her head in her lap. Both girls appeared to be sleeping. The resemblance to a dark fairytale was obvious.

Robbed of the chance to reach their 10th birthdays, Karen and Nicola would forever be remembered as the Babes in the Wood.

Only now has the murder inquiry ended, 32 years later, with an Old Bailey jury convicting Russell Bishop of sexually motivated murder.

Yet at first it had seemed so straightforward. It became clear that both girls had been sexually assaulted. The bloodstained froth around Nicola’s lips made it pretty obvious they had been killed by strangulation. A bruise on Nicola’s face suggested the possibility that she had been battered into submission by a lone attacker intent on violating two little girls.

And fairly quickly, the police had their man in custody.

Freed to strike again

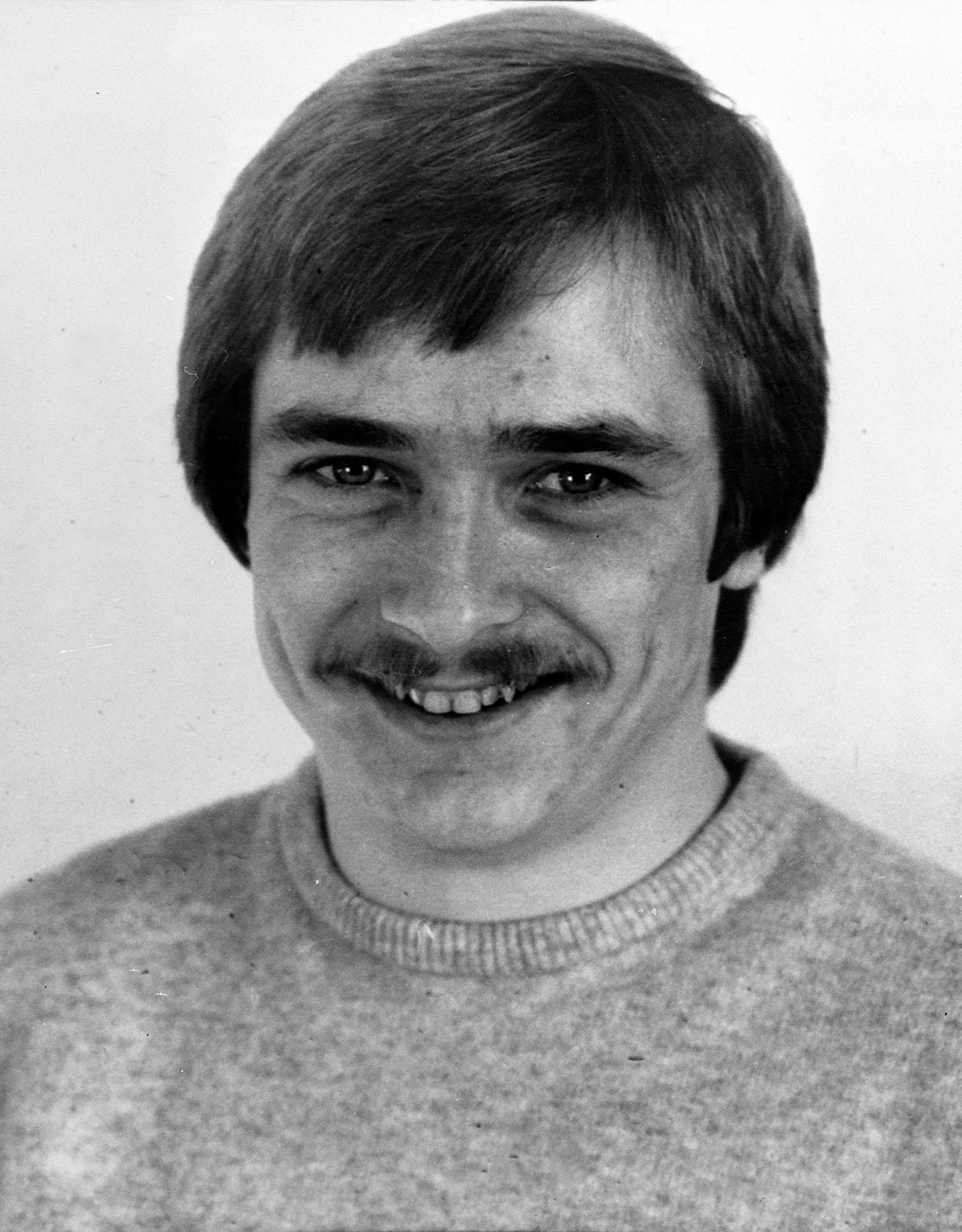

Unprepossessing and unemployed, 20 years old with a 16-year-old lover, Russell Bishop was by all accounts “no criminal mastermind”, “stupid” and “very thick”.

Yet somehow he got away with murder.

In 1987 it took a Lewes Crown Court jury just two hours to find him not guilty.

Bishop walked free – free to pose as a victim of injustice, free, even, to join Karen and Nicola’s parents on a protest march demanding the police catch “the real killer”.

And free to strike again.

On 4 February 1990 Bishop grabbed a seven-year-old girl off a Brighton street, bundled her into the boot of a stolen car, and strangled and sexually assaulted her before leaving her for dead at the Devil’s Dyke beauty spot in Sussex.

This time, though, by a near miraculous stroke of luck, the girl survived, to become what one veteran detective described as “an absolutely exceptional witness”.

In December 1990 Bishop received a life sentence for attempted murder, kidnapping and indecent assault.

Despite becoming eligible for parole release 14 years ago, he remained a Category A high security prisoner, arriving at the Old Bailey as a man so dangerous he had to be manacled for the short walk from the dock to the witness box. He has been referred to as “Britain’s longest serving sex offender prison inmate not to have been convicted of murder”.

Now that Bishop at last has a murder conviction, one vastly experienced crime reporter is prepared to go further and suggest to The Independent that the 52-year-old is “probably one of the most dangerous paedophiles in Britain”.

But two questions remain unanswered: how did such a dangerous man walk free to inflict terrible suffering on another innocent child? And why did it take more than three decades before Karen and Nicola’s families were granted what they never stopped fighting for – justice for the Babes in the Wood?

“Thirty two years,” says that veteran journalist, Phil Mills, the former crime correspondent of Brighton's local newspaper The Argus. “Thirty two years times 365 days of waking up and feeling that horror for the loss of your child. That’s a lot of suffering.”

‘Virtually the whole estate went out searching’

Moulsecoomb has changed over those years. The Hiker’s Rest pub where Bishop and Nicola’s father Barrie Fellows both used to drink has long since changed its name. It’s mainly students that go there now.

In Newick Road, where Karen and Nicola lived and played, evidence of a mini-influx of politely spoken students is also easier to find than the rusting cars and decaying front garden washing machines that were such a feature of the Moulsecoomb of old.

The ‘old timers’, though, are still there, and they still remember.

“How could they ever be forgotten?” says one 81-year-old great grandmother. “They were lovely little girls.”

Her daughter had been playing with the two nine-year-olds for some of the earlier part of that afternoon on 9 October 1986.

Ever since, she has wondered what would have happened if her daughter had stayed with Nicola and Karen: “Would we have been looking at three girls missing, or would all three of them have been able to grow up and become what my daughter is now – a 41-year-old mother with three children of her own?”

Karen Hadaway was still in her school uniform when she left her house for the last time. Her mother Michelle, 29 and heavily pregnant in October 1986, informed her that her tea was already in the oven and told her not to be long. Karen promised to be back soon.

Nicola’s last words to her mother were: “I’m just going across the road. I won’t be long.”

When the girls failed to return home for their tea, both mothers started to worry.

As evening became night, word spread round the estate that two kids were missing, the news also being relayed via the very 1980s phenomenon that was CB radio.

The 81-year-old makes no effort to disguise the fact that in the 1980s Moulsecoomb was the place where the council dumped families evicted from other estates, but she takes defiant pride in saying: “You won’t get a better sense of community.”

On what was a cold, misty October night, she says “virtually the whole estate went out searching”.

‘I saw the tape...’

Michelle Hadaway searched through the night. At about 4.15pm on Friday 10 October, she stopped for a brief rest.

Thirty two years later she told the Old Bailey: “I was exhausted, petrified, worried about my little girl, worried about both those children.”

Suddenly she saw police swarming everywhere. She saw the cordon being erected.

At the Old Bailey, Ms Hadaway could only say “I saw the tape …” before breaking down in tears in the witness box.

After recovering her composure, she recalled how from her resting point in Wild Park she had shouted to someone to ask them what was happening.

That someone was Russell Bishop, joining the search in what the prosecution called “a cynical attempt to divert attention away from himself”.

Bishop looked at the mother of one of the girls he had killed and put his hand over his face, as if sharing in her grief.

The police, as Mills recalls it, “went through Moulsecoomb like a dose of salts”. About 100 officers were tasked with speaking to every one of about 7,000 residents, spending up to two hours in each home.

This was to become the biggest investigation Sussex Police had ever conducted. The commitment of officers, many of them parents themselves, could only have been strengthened by the gruesome postmortem evidence that would later be cited by the prosecution: Nicola had been sexually assaulted after her death, as well as before.

A ‘pantomime villain’

On the estate itself, people were out for blood. At a memorial service held three days after the bodies were discovered, the local priest, Reverend Michael Porteous, urged a weeping congregation to “erase hatred from your hearts”.

But as she emerged from Holy Nativity Church, Karen’s one-time babysitter Angela Cork, 37, admitted: “If I saw the man who did it now, I would strangle him with my bare hands.”

In this febrile atmosphere, many eyes turned to “the pantomime villain of the estate”: Nicola’s father Barrie Fellows.

There is no escaping the fact that the 37-year-old Mr Fellows was far from universally popular in Moulsecoomb. “Vile” was one of the more unflinching descriptions given to The Independent by someone who added: “Everyone on the estate wanted him to be the murderer because he was so unpleasant.”

With a reputation as a local hardman, with convictions for burglary and handling stolen goods that landed him in jail in his youth, Mr Fellows drew attention to himself in 1984 by calling a public meeting to explain why he was showing and promoting adult pornographic videos.

Nor was his cause helped by his behaviour immediately after Nicola went missing. At about 7.20pm, with still no sign of his daughter, he sat down to eat his tea while his wife went out searching.

His subsequent explanation that it was not yet 8pm, and Nicola had gone missing once before and had turned up safely at a friend’s house, seemed to cut little ice in Moulsecoomb.

Few witnessed what happened after Nicola and Karen were found, when a weeping Mr Fellows came “in a real mess” to the home of one of the two 18-year-olds who had found his daughter’s body.

But everyone heard about him having his tea rather than searching for his daughter.

Some applied what they presumably thought was rough “justice”. The 1987 trial would eventually hear that the Fellows family house, and one they were hoping to move into, were daubed with graffiti which included the words: “Fellows out, you are a murderer, a child molester and a child killer.”

Russell Bishop: ‘A scruffy, insignificant little man’, damned by his own words

Meanwhile, Brighton detectives conducting a real murder inquiry came to a wholly different, considerably better informed conclusion.

Much of the evidence had been given to them by Bishop himself. When he provided a statement mentioning the foam on Nicola’s lips, the detectives knew that Bishop had been close to the bodies when they were discovered – but not that close.

Not close enough to know about the foam, or to be able to tell a friend the precise positions in which the bodies lay. Unless, of course, Bishop was the murderer.

When they arrested him, they received his first but by no means last protestation of outraged innocence: “No, no, it’s not me, f**k off, leave it out.”

It’s true that Bishop did not really match the popular image of what a paedophile should look like.

There was, admittedly, the small matter of his 16-year-old lover Marion Stevenson, a source, perhaps inevitably, of frequent rows between him and his adult partner Jenny Johnson, 20, an office cleaner pregnant with their second child at the time of the murders.

But Bishop was only 20 himself. At 5ft 5in and 10 stone, there was nothing, at that time, of the brutish monster about his physical appearance.

The most noticeable thing about this “scruffy, insignificant little man”, recalled one observer, was his “awful” moustache.

His criminal record was similarly bland. Bishop had been fined £200 for burglary in 1984 and was partial to smoking a bit of dope.

At the Old Bailey in 2018 he made the rather self-aggrandising claim that he had been wrongly arrested over the 1984 Brighton bomb. The more prosaic truth, however, may have been that, as the court also heard, Bishop was partial to nicking car radios and hotwiring vehicles. The arrest, if it happened, may have been because he was trying his luck at some sort of petty crime involving cars parked near the Grand Hotel when the bomb exploded.

As even his own 2018 defence barrister admitted, in 1986 Russell Bishop was “a semi-literate, occasional, not very successful car thief … an occasional burglar.” Not a suspected IRA terrorist.

Nor did there seem to be anything in his upbringing to suggest a mind warped by unbearable childhood trauma.

The worst anyone seemed able to remember was that after educational problems and dyslexia led to him being sent away to a special Catholic school in Worcester aged 15, he ran away and hitchhiked home to Brighton.

His mother Sylvia, described in court by Marion Stevenson as domineering, was a woman of some local repute: a regular at Crufts dog show, author of the highly regarded book It’s Magic: Training your dog with Sylvia Bishop.

With her husband Roy, she maintained a tidy, orderly home.

There were three fiercely protective older brothers.

But as a friend of the Fellows family’s lodger, Bishop was one of the few people the girls knew well enough to trust when he suggested going somewhere. A national newspaper journalist who interviewed Bishop with a pretty much open mind before he was arrested found him so “shifty and horrible” he came away convinced he was the murderer.

A discarded sweatshirt and irrefutable forensic evidence?

The police were convinced too, and they had a lot more to go on than just personality.

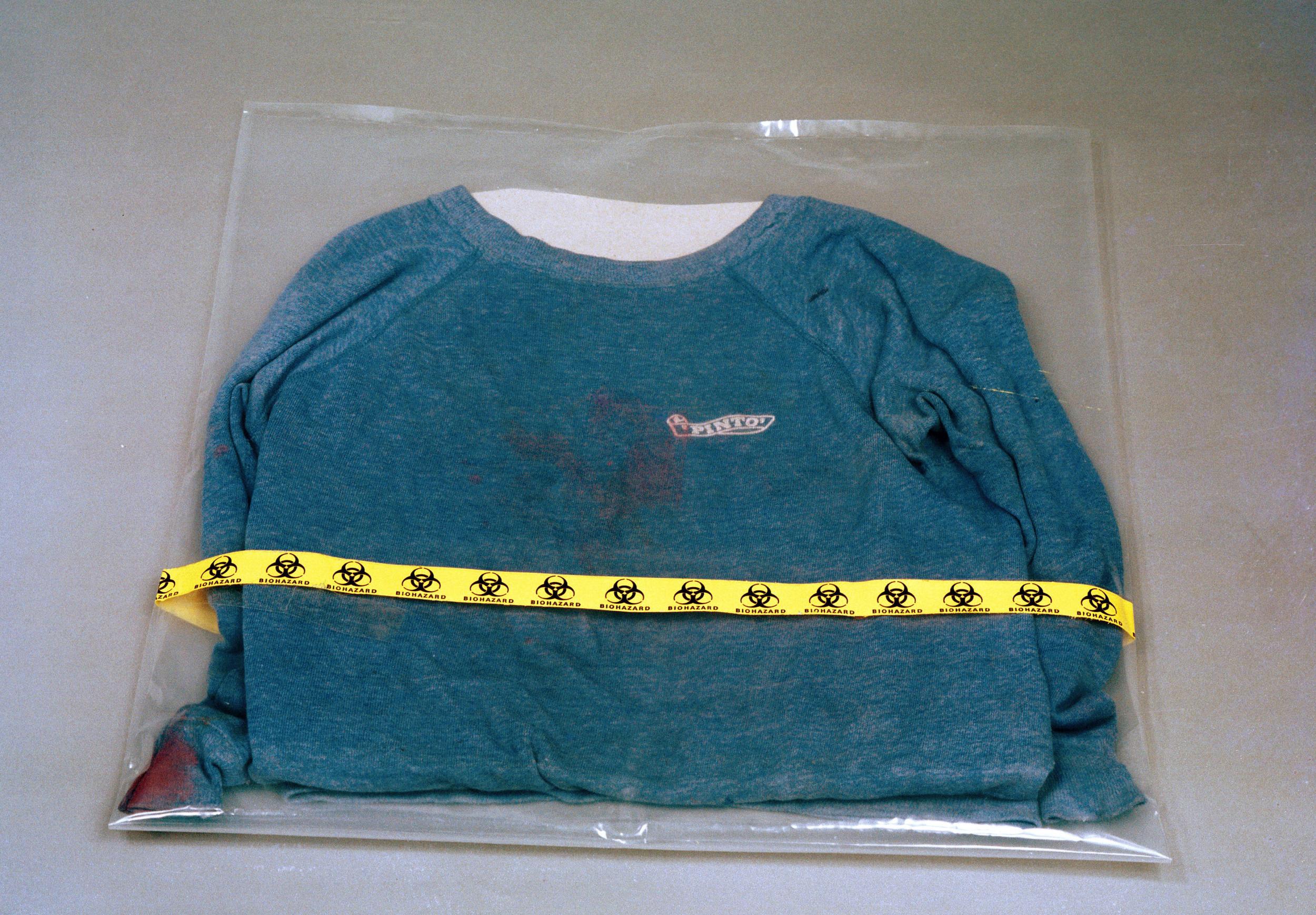

They had – or thought they had – forensic evidence in the form of a Pinto-branded sweatshirt that was linked to both the murder scene and the girls. Fibres from Karen’s green school top and Nicola’s pink jumper were found on the Pinto. Fibres from the Pinto were found on the girls’ clothing. And the 670 star-shaped ivy epidermal ‘hairs’ that had got on to the Pinto suggested that whoever had worn it had entered the ivy-covered ‘den’ where the girls were killed.

Forensics also seemed to suggest the top was Bishop's: four of its fibres were found on trousers taken from his home. Five fibres from one of Marion Stevenson’s skirts were discovered on the Pinto. And paint stains on the sweatshirt matched the maroon colour of a friend’s Mini that Bishop had helped spray.

The sweatshirt, moreover, had been found on the night of the murder, discarded near a footpath that would have been a logical route home for Bishop.

And the police had a star witness in the form of the other woman in Bishop’s life: Jenny Johnson. When officers came to question her carrying the Pinto in an evidence bag so they could ask her about it, she had initially suggested to them that they were “bringing Russell’s sweatshirt back”.

The detectives were convinced: they had nailed him.

Absolute bloody mayhem in court

But that’s not what happened on 10 December 1987 when, after just 129 minutes of deliberation, the jury filed back into courtroom number one at Lewes Crown Court.

The lady foreman returned the first verdict for the murder of Karen Hadaway: “Not guilty.”

Sitting on a packed press bench, Argus reporter Jim Hatley had a ringside seat for what happened next.

It was, he says, “absolute bloody mayhem”.

“There where whoops and screams from Bishop’s family,” says Mr Hatley. “His brother Alec jumped into the dock to try to embrace him.

“The warders were trying to drag Alec away. Sylvia Bishop was sobbing and screaming. There was a scuffle on the public benches.

“Sylvia ended up being restrained by a policewoman as she shouted, ‘If my husband has a heart attack, I’ll kill you’.

“Russell Bishop started pounding his fist on the dock rail and shouting, ‘Shut up! Keep calm!’.

“Then we got to hear the second not guilty verdict.”

‘Police cock-up’ or ‘perverse jury decision’?

Outside court, Bishop’s solicitor Ralph Haeems was able to declaim, at length, about what a disgrace it had been that such a “flimsy, inadequate” case had ever been taken to court.

Although, with the lawyers still clearing their things from court number one, Mr Hatley found a hitherto friendly junior member of the defence team to be strangely reticent.

“The only thing I could get out of him was, ‘My client has been found not guilty under the due process of law’,” recalls Mr Hatley.

Stories began to circulate that Sussex Police, in their fixation with Bishop, had made an amazing series of blunders which culminated in their failure to catch the “real killer”, who – presumably – was still stalking the streets of Brighton.

There was talk of officers failing to preserve the forensic integrity of the Pinto sweatshirt, failing to test the clothing of eight other potential suspects, failing to properly examine items such as “used contraceptives found near the scene”.

It all still rankles with the long-serving detective who spoke to The Independent.

He points out that many of the detectives on the Babes in the Wood case, rather than being the country bumpkins of sneering London condescension, had only recently finished successfully investigating the ‘Brighton bomb’ planted during the 1984 Conservative Party conference.

“Any officer who knew anything about the case,” he says, “remained absolutely convinced Bishop was responsible. It was a perverse decision by the jury.”

No DNA and no confession?

But for Jim Hatley, the neutral observer who sat through the evidence, twice, it was neither a police cock-up nor a perverse jury decision.

Part of the problem, he says, was that with DNA in its infancy in 1986, the forensics, though not contaminated, were not quite conclusive enough: “The science hadn’t advanced enough in those days. Nobody could prove the Pinto was Bishop’s and that he was wearing it at the time of the murders.

“And they couldn’t get a confession out of him, which would have been the usual thing to do in those days.”

Years later, one of the men who interviewed Bishop claimed he had got tantalisingly close when he challenged Bishop to explain how he knew about the foam on Nicola’s lips.

“He went absolutely white,” former Detective Sergeant Phil Swan told the Mail on Sunday in 2006. “His eyes were bulging and he was shaking like a leaf. Experience tells you when they are on the verge [of confessing].

“But then he started screaming, ‘Get him away from me!’ and his lawyer got him out of the room.”

‘The prosecution was pushing its luck a bit’

Having heard all the evidence at an old-style committal hearing before the case even got to trial, Mr Hatley was one of the few people to arrive at Lewes Crown Court willing to bet that Bishop would be acquitted.

“I hadn’t made my mind up about whether or not he was guilty,” he says, “but I thought if he got the right jury he was going to walk.”

“This wasn’t a trial to decide the balance of probabilities,” he explains. “It had to be beyond reasonable doubt. And I thought the prosecution was pushing its luck a bit.”

Although he does also concede: “Considering how stupid Russell Bishop is, he was incredibly lucky to get off.”

‘Your friendly legal eagle who would get you off anything’

It helps, of course, to have a good lawyer.

Ralph Haeems, who died in 2005, was the solicitor who helped get the Kray twins off the charge of ordering the murder of Frank “the mad axeman” Mitchell.

Were he still here to defend himself, Mr Haeems would doubtless explain he was merely a dutiful advocate for all who are accused and have the right to be considered innocent until proven guilty.

Mr Hatley, though, saw him as: “Your friendly legal eagle who would get you off anything … A slippery bastard.”

Mr Haeems instructed Ivan Lawrence QC MP (Conservative, Burton). Together they led the defence team in, as Mr Hatley saw it, trying to “sow enough reasonable doubt”.

To spectacular effect.

Theatrically sowing the seeds of ‘reasonable doubt’

Just how spectacular was revealed in the 2018 trial when some of the highlights were replayed for the benefit of the Old Bailey jury.

“Is it not the case,” asked Joel Bennathan QC, defending, of now retired Home Office forensic science laboratory expert Dr Anthony Peabody: “That as you left the witness box in 1987 you were pinned against the wall by a senior officer?”

“As it happens,” replied Dr Peabody. “Yes.”

With his bow tie and precise manner, Dr Peabody in 2018 appeared to be the kind of scientist who does not take kindly to having his professional authority challenged by lawyers.

In 1987, while still under crossexamination, he had taken the rather extraordinary step of producing a notebook and starting to take a record of proceedings while still in the witness box.

Mr Lawrence had asked him why he had only noticed dog hairs on the Pinto after a defence expert had spotted them.

“Are you suggesting this witness tampered with evidence?” interjected Mr Justice Schiemann.

Mr Lawrence assured the judge he was merely pointing out “an interesting coincidence”.

“I must remind myself that this allegation has at least been aired,” said Dr Peabody as he began writing. “I have not tampered with anything.”

During the crossexamination, Mr Lawrence also asked Dr Peabody: “You are not saying scientifically that the Pinto sweatshirt was worn by the murderer?”

“No, I am not,” confirmed Dr Peabody, insistent as ever on scientific exactitude.

“All you are saying is that it could have been,” invited Mr Lawrence.

“Yes,” replied Dr Peabody.

At one point during the crossexamination, according to the book A Question of Evidence by Christopher Berry-Dee, watching police officers were seen with their heads in their hands.

In Mr Hatley’s estimation, by the time others had testified and Dr Peabody had left the dock for his tete a tete with a senior detective, the ground on the forensics linking the sweatshirt to Bishop and the murders had slipped from certainty to mere possibility.

But the prosecution still had their star witness – didn’t they?

Jenny Johnson: the star prosecution witness who wasn’t

Jenny Johnson entered the witness box and proceeded to say the precise opposite of what the prosecution had been expecting.

She had talked to the police about them returning the crucial sweatshirt, but only because her poor eyesight had confused her into mistaking the Pinto – not owned by the defendant – for a top that was owned by Bishop.

Yes, she added, she had signed a statement saying Bishop owned the Pinto sweatshirt. But that was because she was in a rage with him and wanted revenge after the police officers told her he was still carrying on with her teenaged love rival Marion Stevenson.

Bishop had never owned the sweatshirt, Ms Johnson told Lewes Crown Court. She had never seen it before the police showed it to her.

With that testimony, said Mr Hatley, the attempt to link Bishop to the possibly incriminating Pinto sweatshirt “fell through the floor”.

He offers a world-weary shrug.

“It was an estate full of lies. With some people in Moulsecoomb, it was a case of, if you see a copper tell them a lie.”

“There was,” he adds, “industrial-scale lying.”

Mrs Black, Mrs White and Miss Brown

Intimidation may also have added to the confusion. Three witnesses gave evidence anonymously.

Five years before Quentin Tarantino directed Reservoir Dogs, Mrs Black, Mrs White and Miss Brown were referred to in court according to the colour of the tops they wore in the witness box.

Bishop, though, declined to give evidence.

Mr Hatley thinks his lawyers realised their client might “talk himself into trouble”.

They preferred to pick holes in some of the prosecution’s timings, to go with the alleged holes in the forensics.

If the timings don’t fit you’ve got to acquit?

On the first day of the committal hearing, in February 1987, the prosecution had rhetorically asked where Bishop had been between about 5pm on the evening of the murders and being spotted emerging from Wild Park at 6.30pm.

But 10 months later, during the 1987 trial itself, Mr Lawrence produced witnesses who testified to having seen Karen and Nicola alive at about 6.30pm, when Bishop was leaving the park where the girls would eventually be killed.

“If the girls were alive at 6.30pm,” Mr Lawrence told the jury, “then an already weak and feeble prosecution case is shot to pieces.”

It was noticeable that when Brian Altman came to open the case for the prosecution in 2018, he too said the girls were alive at 6.30pm. But he added a crucial rejoinder to the evidence that Bishop had been seen heading home from the park at 6.30pm: “If the defendant was heading in the general direction of his home, then the defendant must have turned back into Wild Park.”

But that was in 2018.

In 1987, Mr Justice Schiemann, officiating at his first murder trial, reminded the jury: “Our law provides that you are not to convict any individual of any crime, be it never so grave or never so pretty, unless you are sure he is guilty of that crime. I cannot emphasise that too much.”

After the jury had thought about it for two hours, and after the subsequent pandemonium subsided, Bishop walked out of Lewes Crown Court a free man.

‘Absolutely sickening’

He entered with gusto into his new role as a wronged man who had been accused of a crime he didn’t commit.

On 19 August 1989 the killer joined Karen and Nicola’s grieving families on a protest march through Brighton to the police station.

Secure in the knowledge that Britain’s double jeopardy rules prevented him from ever again being tried for Karen and Nicola’s murders, Bishop gave interviews demanding that the real killer be caught.

As the girls’ families were filmed repeating their pleas for justice for the Babes in the Wood, Bishop could be glimpsed in the background giving an interview to another TV crew.

For the officers watching from inside the police station, it was, the veteran detective recalled, “absolutely sickening”.