Why? Why us, why here, why that day of all days; but most of all why our girls, our tiny excited girls, happily making bracelets for each other in a summer holiday workshop?

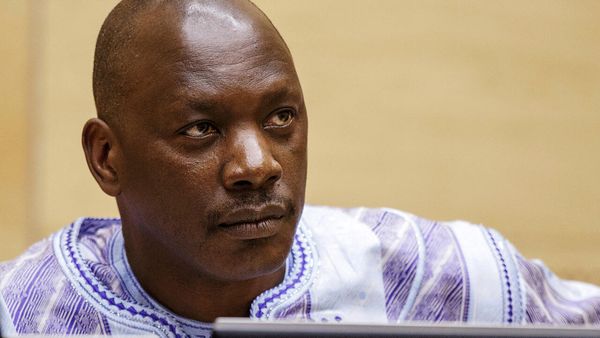

Such questions that must have been tormenting Southport families ever since last July, when a then 17-year-old Axel Rudakubana brutally murdered three of their children and tried to kill eight more (as well as two adults) in what prosecutors this week called a “sadistic” attack. The parents got no answers from the dock, where the boy – now man – who took their daughters sat silent, but for some oddly petulant outbursts against the judge. But in a sense the question is unanswerable. No motive, no twisted ideology or mental illness, could ever explain stabbing a six-year-old. Debating whether or not this was terrorism “misses the point”, the judge said as he sentenced Rudakubana to 52 years in prison. He would have killed them all if he could.

Though some will fall back on biblical notions of evil to explain the seemingly unfathomable – one tabloid writer claimed to “see the devil” in Rudakubana’s eyes – we do not live in a time of demons and witches. We live in a world where human beings can do unspeakable things; where society’s job is to find and fix the cracks through which such horror slips. The question governments must ask isn’t why but how, so that we can ensure it never happens again.

This case has been dogged throughout by claims of a cover-up, so the prosecution spoke not just to a court but to a country in sketching out the case they would have made had he not unexpectedly pleaded guilty. It was the story of a reclusive teenage loner, obsessed with violence, on multiple authorities’ radar for years but never seemingly seen for the danger he was. Diagnosed as autistic and suffering from anxiety, he was expelled from school for carrying a knife into class in 2019 and seemed to want revenge on children he claimed had bullied him. (He returned to attack one child with a hockey stick and prosecutors suspect him of planning a mass attack at his old school, foiled by his father physically stopping him getting in a taxi.) Seemingly obsessed with genocides like the one his Rwandan-born parents fled, he spent hours online watching videos of atrocities; his computer held images of torture and beheading, but also cartoons mocking Islam and other religions.

Was he somehow traumatised at one remove by his parents’ experience of a war that, growing up in Britain, he’d never known? Or was this just where his macabre fascinations found an outlet? He can’t or won’t say: once again, the “why” eludes us. But the “how”’ is grimly clear. He ricocheted between social services, mental health services, police and the anti-radicalisation programme Prevent, to which he was referred at least three times in three years – including for researching school shootings and the London Bridge terror attack – yet each time judged below the threshold to act. As Keir Starmer put it, the failure to stop him emulating that violence in real life “frankly leaps off the page”. The law may need revising to cover attacks lacking a clear ideology – the “why?” that distinguishes terrorism from other violence – which sounds technical, but potentially determines whether deradicalisation programmes engage with people like Rudakubana or not.

Though Starmer suggested this case exemplified a new form of terrorism, it’s hardly new to anyone working in the field, which raises questions about whether previous home secretaries could have acted earlier. For years the authorities have grappled with what Americans call “salad bar extremism”, or lone individuals self-radicalising by picking seemingly at random from the internet’s all-you-can-eat buffet of conspiracy theories and grievances. An attacker might be radicalised in an “incel” chatroom, take inspiration from some school shooter’s manifesto, and glean their method from jihadist manuals like the one Rudakubana downloaded – but without becoming a jihadist.

Ken McCallum, the head of MI5, warned last October of an increase in “more volatile would-be terrorists with only a tenuous grasp of the ideologies they profess to follow”, leaving authorities unsure if the root cause was ideology or mental health – the question ministers come under intense pressure to answer in the confused aftermath of an attack. In that vacuum of understanding, as we saw in Southport, tensions erupt.

Though the last government published a review of Prevent by William Shawcross in 2023, the then home secretary Suella Braverman seemed mainly preoccupied with whether too many far-right suspects and not enough Islamists were being investigated, attacking “cultural timidity”. Shawcross meanwhile concluded Prevent had become a dumping ground for vulnerable people who didn’t fit the terrorist definition but do, in retrospect, sound more like Rudakubana; what Starmer called “loners and misfits”, falling down rabbit holes online. Shawcross felt Prevent should return to its core function of “tackling the ideological causes of terrorism”. One pressing question is whether, in narrowing Prevent’s scope, anyone properly considered where those pushed out of it would go. Last month, the home secretary, Yvette Cooper, announced a review of Prevent thresholds and more oversight of those it turns away, which suggests she has drawn her own conclusions.

What drives so many young men (it’s usually men) towards what Starmer called “parallel lives”, dangerously adrift from others? Cooper’s review will examine the role of mental health problems and neurodivergence, a sensitive subject given the worry about stigmatising sufferers, but one reflecting growing concerns within Prevent about lonely, socially isolated people seeking comfort and belonging online.

The coming public inquiry should also examine whether Rudakubana slipped off the radar during lockdown – as too many children did, though most were more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence – and if not how he could be known to so many children’s services to so little avail. Parents who have encountered those services may be less surprised by that than those who haven’t. What all tend to have in common is thresholds to act rising as resources to act shrink, and children being endlessly shunted from one caseload to another. Though ministers are right to clamp down again on extremist content online, and on knife sales, these actions alone won’t solve the problem.

My heart goes out to the bereaved and the survivors in Southport, who will bear the scars inside and out for the rest of their lives. We may never have answers to all their questions. But understanding exactly how Rudakubana came to walk that long dark road to tragedy, however painful that is, remains our best chance of preventing it ever happening again.

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.