Arnold Schwarzenegger recently made the claim that climate change has an image problem. He railed against what he thinks is an overemphasis on degrowth and bad optics:

As long as they keep talking about global climate change, they are not gonna go anywhere. ‘Cause no one gives a s*** about that. So my thing is, let’s go and rephrase this and communicate differently about it and really tell people we’re talking about pollution. Pollution creates climate change, and pollution kills.

Whether or not a rebranding exercise will be enough to shift perceptions is as yet unclear. But calls to recognise the power of emotions to drive change are becoming increasingly relevant in motivating action.

In his new book Awe: The Transformative Power of Everyday Wonder, psychologist Dacher Keltner claims emotions like awe “unite us into something larger than the self” and can lead to a better relationship with the natural world.

But what exactly is awe and how can emotions help us save the planet?

Review: Awe: The Transformative Power of Everyday Wonder – Dacher Keltner (Allen Lane)

The science of emotions

For a long time, attempts to understand the mind’s responses to reality were grounded in experimental psychology. This involved focusing attention on the internal mental processes at the heart of human behaviour.

In the 1950s, a movement that became known as the cognitive revolution reacted against the behaviourism that had come to dominate the field of psychology. Its approach was to treat the mind like a computer, seeking to understand its parts and the relations between them, but neglecting its more fallible and subjective elements.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that scientists and psychologists came to appreciate the importance of emotions to understanding the secrets of the mind. American psychologist Paul Ekman would lead this paradigm-shift with his study of facial expressions and their relationship to emotions. His work was instrumental in understanding the non-verbal language of the body.

Acknowledging the multifaceted nature of psychology led to the evolution of emotion science – a combination of empirical investigations with meta-studies of non-observable phenomena.

Strides were soon being made in research examining the hidden side of the brain and a new understanding of emotions emerged. Some of the first emotions to be charted scientifically included anger, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise and joy. These were soon followed by more positive states, such as gratitude, love, desire and sympathy. Much of this early work is still relevant today and serves as the bedrock for more normative claims around improving one’s emotional intelligence or EQ.

Scientists such as Ekman speculated about why we have emotions. They posited the place of emotions in the evolutionary hierarchy of human capabilities, viewing them as experiences that enable self-preservation by alerting us to danger or helping us to find nutritious food. This evolutionary bent has led to a view of emotion as “oriented towards minimising peril and advancing competitive gains for the individual”.

Rule breaking emotions

Influenced by the work of Ekman and others, Keltner recognises the limits of the cognitive revolution. He seeks to develop a holistic view of the mind. “What was missing from this understanding of human nature was emotion,” he writes. “Passion. Gut feeling.”

According to Keltner, awe does not fit comfortably within a deterministic theory of emotion:

Awe, by contrast, seems to orient us to devote ourselves to things outside of our individual selves. To sacrifice and serve. To sense that the boundaries between our individual selves and others readily dissolve, that our true nature is collective.

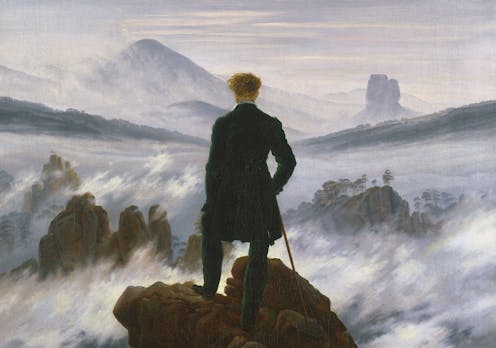

Keltner’s research suggests awe occurs in response to the “eight wonders of life”. It can be found in nature, collective movement, visual design, music, mystical encounters, life and death, epiphanies, and the courage and kindness of other people.

When people experience feelings of awe, they enter a unique physiological and psycho-social state, which culminates in a sense of appreciation and positive emotion. For example, in a study of 1,100 travellers from 42 countries who visited a lookout in Yosemite National Park, researchers found awe has the power to temper human inclinations towards individual interests and concerns. Experiencing a sense of awe alters our sense of self and opens us to the possibility of collaboration and a sense of community.

In another study conducted on the benefits of walking in nature, it was found the sense of wonder generated during these walks led participants to feeling less anxiety and depression, with notable increases in expressions of joy.

Given these life affirming characteristics, can awe provide the missing link between science and emotion that is required to generate action on climate change? For Keltner, the answer is yes:

Our default mind blinds us to this fundamental truth, that our social, natural, physical, and cultural worlds are made up of interlocking systems. Experiences of awe open our minds to this big idea. Awe shifts us to a systems view of life.

Systems thinking

Applied to different contexts like biology, technology, organisational theory and culture, systems thinking takes a holistic view of the many parts that make up the world and the interdependent relationships between them. Systems, according to Keltner’s definition,

are entities of interrelated elements working together to achieve some purpose. When we look at life through this systems lens, we perceive things in terms of relations rather than separate objects.

In contrast, linear thinking involves understanding processes of cause and effect, whereby analysis follows a known step-by-step progression. Isaac Newton’s observation of an apple falling from a tree, for example, led him to develop a causal theory of gravity. The effect, an apple falling from a tree, is caused by the force of gravitational attraction between objects.

Yet the same process has different implications when it is viewed within a systems-thinking approach. In Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, gravity is understood as part of a larger system of matter, energy, space and time. The paradigm shift offered by a systems-thinking approach can transform how we understand reality.

The implications for approaching the world through a systems-thinking framework are wide-ranging. Understanding how environmental processes influence each other has consequences for environmental sustainability. For example, instead of building more dams as part of a flood prevention strategy, a systems-thinking solution would be to preserve and restore wetlands that act as sponges during floods.

A more holistic approach to environmental systems governance can yield better outcomes by moving away from individual interests towards decisions that maintain and support interdependent relationships.

The key is to identify the intricate relationships between natural phenomena to seek solutions that operate successfully within existing environmental conditions. Instead of observing and analysing entities and processes individually, systems thinking leads to a greater awareness of the fragile interdependencies that constitute all life on earth.

Keltner observes that many Indigenous civilisations have long operated with a systems-thinking approach:

Systems thinking, it is worth noting, is at the heart of an Indigenous science now thousands of years old. It is an old, big idea. It may be our species’ big epiphany.

As a result of generations of cultural erasure, much of this knowledge has been lost or destroyed, but Keltner believes it is still possible to experience the world with a sense of awe:

Mysteries awaken us to systems. Look to the sky and listen for migrations of birds. Follow the tides. Watch the growth of a seedling and its relationship to the earth.

Read more: Saving humanity: here's a radical approach to building a sustainable and just society

Cultivating awe

Keltner also considers the ways that culture represents and shapes our experiences of awe in the form of music, visual art, religion and spirituality. Many of the examples he gives emphasise the importance of discovery:

In musical awe we hear the voices and feel the sounds of our culture. We recognise, we understand, our individual identity within something larger, a collective identity, a place, and a people.

The key is not to extract more from the world. Instead, Keltner thinks awe can help unlock truths within ourselves that are buried by external forces, such as capitalism and economics, reorienting us away from a self-serving, hyper-individualistic and materialistic characterisation of human nature. Cultivating awe leads to an awareness of interconnectedness. It encourages people to engage with activities and experiences that force then to think about humanity’s place in nature as being part of a much larger whole:

In our narration of experiences of awe in these symbolic traditions, a clear motif emerges: our individual self gives way to the boundary-dissolving sense of being part of something much larger.

Keltner does not make any claims for how emotion can motivate positive action. Living a life filled with awe does not guarantee an ethical approach to nature, nor is there any proof that encouraging others to approach the world with wonder will lead to action on climate change. But the practical examples and observations of awe provided in this book suggest that emotions do transform perceptions and can lead to meaningful change.

The epiphany of awe is that its experience connects our individual selves with the vast forces of life. In awe we understand we are part of many things that are much larger than the self.

At very least, these examples of awe serve as a testament to the power of nature to move the human spirit, and if that is not enough to motivate greater care for the environment, then perhaps nothing is.

Nanda Jarosz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.