The UK faces some significant belt-tightening following Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement, which announced spending reductions and tax rises of around £55 billion. Much research has been done into the best ways to do fiscal austerity in terms of reducing debt, avoiding economic damage and not exacerbating inequality. So how does this attempt measure up?

That £55 billion retrenchment includes over £30 billion of reduced annual government spending by 2027/28. Over the next couple of years, the government is actually going stick to previous spending plans and even increase them for core departments like health and social care. But from 2025-28 there will be a crackdown, with maximum 1% real-terms increases for day-to-day (current) spending, and infrastructure (capital) spending only being maintained in cash terms.

Our research, which looked at the US finances between 1985 and 2016 but is applicable to many countries, has found that austerity based on public spending cuts often costs the overall economy less than tax rises. Spending cuts are usually followed by reduced interest rates, which can spur consumption and business investment.

Previous findings based on data around the world dating back as far back as the 1960s have reached similar conclusions. In contrast, tax rises disincentivise consumption and investment by whoever is on the receiving end of them.

Having said that, cuts to capital spending weaken the overall economy longer term by making a country less productive. Unfortunately, governments tend to see this as more appealing than immediately unpopular cuts to current spending. Nearly half of Hunt’s spending cuts fall into this category.

Even if the government had cut spending in the “right” way, there’s still an ugly trade off. Our research suggests that spending cuts are associated with greater income inequality than tax rises, disproportionately affecting those on lower incomes.

The most obvious example is the UK’s early 2010s fiscal austerity, which caused a clear rise in both absolute and relative poverty. The government may again be calculating that it takes a while for people to see the effects, thereby minimising the political cost in the short term.

The tax situation

The chancellor’s austerity package also entails measures that will increase taxes as a proportion to GDP to over 37% by 2023/24. Historically this figure has averaged 32% since 1948.

The rise will partly come from maintaining the corporation tax increase announced when Rishi Sunak was chancellor, plus increasing windfall taxes on energy companies. Income tax thresholds are also being frozen so that over time, more people will pay the 20% and 40% basic and higher rates than at present, while the top 45% rate will kick in at £125,000 instead of £150,000.

Tax hikes do more harm than spending cuts to GDP in the long run because they distort the economy. For example, higher taxes on company profits lead to higher prices for goods. This reduces the incentive for households to invest indirectly in firms by buying as many of their goods, which weakens business investment and so on.

On the other hand, governments can enhance their political credibility by taking a tough decision, particularly when it goes against the instincts of the ruling party. The Conservatives choosing to raise corporation taxes from 19% to 25% by April 2023 as opposed to, say, rowing back on the Sizewell C nuclear power plant or the HS2 rail project, would certainly be an example.

The government could arguably have gone further here by, say, making tougher changes to capital gains tax or inheritance tax. Admittedly, however, it is difficult to win a great deal of political credibility when your party is so low in the polls already.

Debt

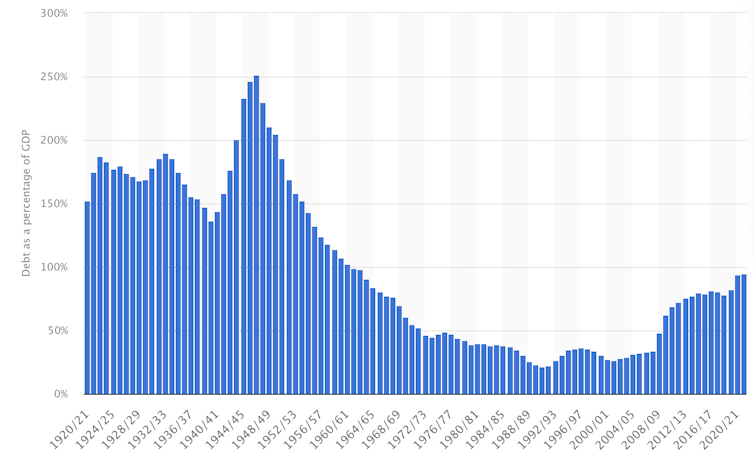

As it stands, the government’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that total UK public debt will rise from 102% of GDP in 2022/23 to 107% the following year, before easing to 99% by 2027/28. But if the autumn statement is to reduce the national debt, tax revenues will have to improve considerably. Is this likely?

The income tax changes will raise the average marginal tax rate in the UK, meaning the tax paid on the next £1 of income. Our research demonstrates that tax rises that increase this marginal rate raise less revenue as they disincentivise high-income earners.

UK debt as a % GDP since 1921

When combined with the OBR under-forecasting the impact of taxes on the economy relative to the existing empirical evidence, we suspect that its tax revenue forecasts are overstated.

Of course, this may be offset by an understatement on inflation. The OBR is assuming very low inflation from 2024, but there are various reasons why it could come in much higher. If so, that would reduce the real cost of the debt by more than the OBR anticipates.

Meanwhile, it does not help that the government has maintained the “triple lock” on pensions, which stipulates that the state pension will increase each year in line with whichever is the highest out of consumer price inflation, average wage increases or 2.5%. With the UK’s ageing population, the OBR forecasts that the triple lock will help increase state-pension spending from 5% to 8% of national income over the next 50 years. Prolonging the triple lock again suggests putting politics ahead of what’s best for the economy.

Playing politics

Overall, retrenching the public finances means balancing numerous trade-offs delicately to have any realistic chance of reducing debt reduction, economic stability and avoiding higher inequality.

By both cutting spending and raising taxes, the chancellor has designed a relatively balanced package. However, there is clearly an aversion to taking difficult decisions, including pushing back spending reductions until 2025-28, prioritising cuts in capital spending and protecting the pensions triple lock.

In the same vein, the tax changes will increase the average marginal tax rate slowly as incomes rise. This is consistent with the Conservative 2019 manifesto pledge not to increase tax rates, but it will discourage work and investment, further undermining long-term productivity.

It goes to show that even during an economic crisis, the UK government’s instincts are still to make highly political decisions.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.