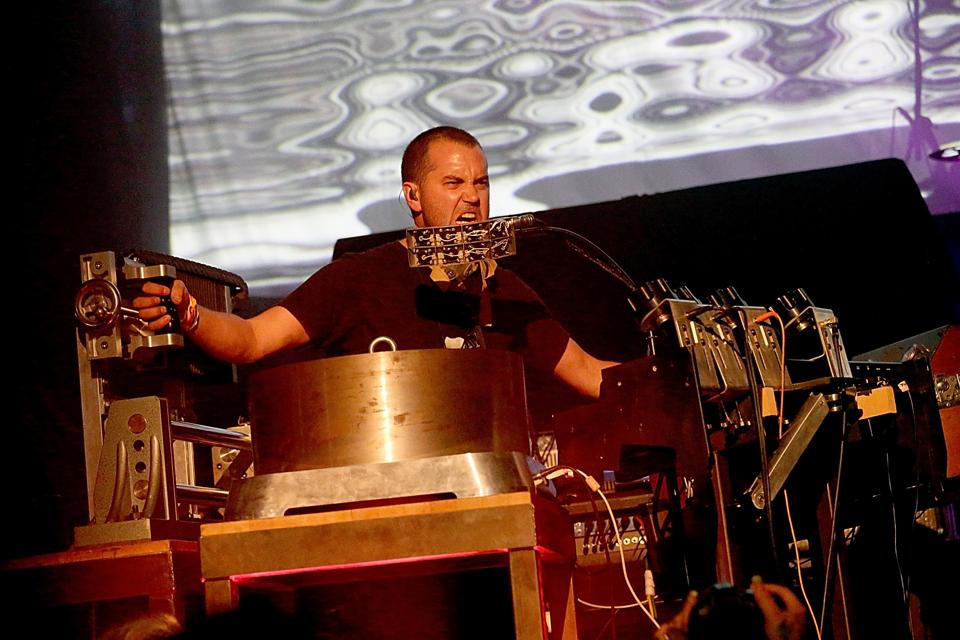

Metal’s one man act, Author & Punisher, has stood out as a notable deviation from the norm of today’s heavy music scene. For over a decade Tristan Shone (Author & Punisher) has brought a beautiful cacophony of industrial rhythms and gritty melodies across eight studio albums. Having carved out a rather niche but unique corner for both heavy and experimental music lovers, Author & Punisher has now come to a vital turning point in its legacy.

Krüller, A&P’s ninth and most progressive studio album yet, has set an ambitious trajectory that’s already being met with waves of critical praise. Building off the sonic foundation of obscure instrumentation and ominous sound design, Tristan Shone has filled in the gaps with the inclusion of melodic hooks over sheer abrasiveness on Krüller. Much of which is actually highlighted by the album’s featured instrumentalists, namely Tool’s rhythm section Danny Carey (drums) and Justin Chancellor (bass), as well as guitar work by Phil Sgrosso (As I Lay Dying, Saosin).

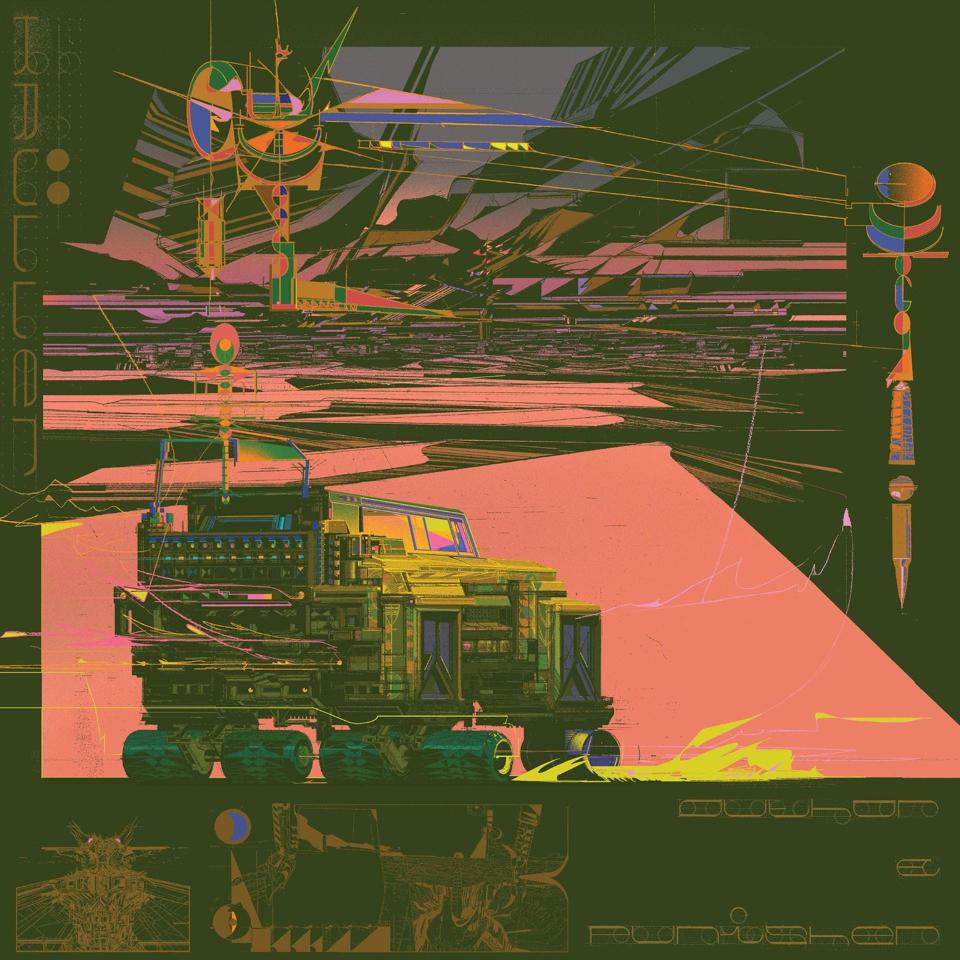

Wielding ferocious industrial doom metal that’s embellished with sharp hints of synth-wave, Krüller is undeniably Author & Punisher’s most eclectic work to date. However, beyond its dense and innovative sonic landscape, the lyrical themes that Shone brings to light paint a not so distant future. Taking inspiration from the Sci-fi works of Octavia E. Butler, Krüller gives relevant commentary on today’s polarizing social-political topics like climate change, war, and the response to the pandemic. The weighty dystopian subject matter fits right into Author & Punisher’s mechanized grooves and eerie drones. This, combined with the embrace of Shone’s harsh Type O Negative-esc vocals, makes Krüller bound to connect with an array of heavy and experimental music fans.

Discussing the conception of Krüller and his newly announced audio gear company, Drone Machines, Author & Punisher’s own Tristan Shone dives into the details.

What was the vision going into the writing process for Kruller? The density of melodic and heavy layers is unlike most of your previous work.

Basically when the pandemic started I was on tour with Tool and we were cut short by about four shows. From that tour we recorded every show and for me those were the best possible conditions to play in. I had a crew, I was also able to access the Tool crew because they would listen to it every night, and I had the best sound system. So when we recorded everything and I got back home and everything went to hell, I was able to give myself a really honest look from almost a fan perspective. I wasn’t thinking about “oh I have to fix this thing,” it was “okay I probably have like I a couple of years of no shows, what does this sound like?” It was like looking at yourself in the mirror and saying from a fan perspective, “does this sound good?” There was some really good things that I liked but there were also some elements that I hadn’t really looked at closely. I think vocals and melody, and just sort of the overall abrasiveness I was always going for with heavy and dark, I think some of it hit those angsty tones that I don’t usually like to hit. So this record was more about finding the balance between heaviness and melody.

What’s the meaning or thought behind the album title, Krüller? Is it pronounced ‘Cruel-ler?’

Yeah however you want to pronounce it. The idea of the title was basically like when I sat down with Zlatko Mitev — the artists who made the album artwork — in the beginning of the pandemic we started looking at this real broad separation between left and right in the US and these survivalist mentalities. There’s this one side that’s driving around in their very militarized Toyotas Tacomas and sprinter vans with gas tanks on the back, like these dudes are ready for war and their fantasy is to go this route. For me to think about the books I was reading like Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, we are living that moment, this ‘dystopic’ moment that we read about and watched movies about. For me the lyrics, the cover, Krüller is really like my sort of...if I were to write my own sci-fi novel that is a vehicle that would be in that novel. It’s the truck, it’s the survival vehicle and I’m not on the side that wants to kill people, but rather part of the people that still want to remain humans and maintain art and humanity. I just feel like so many people here in this country just want to fight, and they just want blood, and that’s not what this album is about.

The album has some notable features on it as well, from Phil Sgrosso on guitars (As I Lay Dying, Saosin), and both Danny Carey and Justin Chancellor from Tool. How did all of these features come together?

Yeah well Phil’s been my manager for the last few years, and I’d known Danny [Carey] for a while before the tour, and Justin [Chancellor] I had met on the tour and we just kept in-touch. Justin and I had wanted to do a track when I got back and we just started sending tracks back and forth and so it was very smooth. And for Phil, it was going to just be a lead on a part and then it turned into a “hey I added some extra stuff,” and then before you knew it he just threw a bunch of stuff on every track. And then Jason Begin who’s my partner in Drone Machines, he has worked on a lot of my records and he’s not a metal guy, he’s more into Aphex Twin sort of glitch-stuff. And so he’s one of these synth-guys, and I’m more of a software VSTs sort of guy, so my sounds don’t always have the best high-end fidelity, and Jason just took everything and made it sound better and more lush.

When did you realize you’d want to start producing and distributing gear through your own Boutique Audio Company, Drone Machines?

Well I’ve really held back from doing this for a long time just because there’s a lot of logistical elements. If I were 25 I think I would have irresponsibly gone right into it, and the music gear industry isn’t a money maker, this isn’t about making money it’s about getting to the point where I want to make more stuff for myself, and I want to be able to experiment. I can only make so many things with the touring schedule, so I found two people that can take that load off of me a little bit more; Adam Reed-Erickson, who’s a mechanical engineer, and Jason Begin. Between the three of us we sort of found a way to balance and ask how do we make the electronic and techno music worlds more tactile, and how do we get people into this? Because electronic music is the future of music, and so how do we get people to have a more intimate relationship with their devices so that live music isn’t just button pressing, and you’re not just stuck in a 1 foot by 1 foot square on stage? I want people’s motions to be based on human movement, not just micro movements of fingers, so that’s what we’re trying to do.

And also we’re making it open source, so if you spend $1,500 dollars on a device you’re not going to be stuck with something that’s going to breakdown very quickly. It’s no plastic, it’s all stone, metal, wood, and steel. Open source electronics allows someone to develop this over the years so that if there’s a different change in protocols, if USB-C and USB-A go away you can swap that component out. You can still use the hardware but you can change out the things that are going to be obsolete.

What’s your general philosophy when it comes to choosing, as well as crafting the type of gear you use for A&P?

I love that question because I think that one of the things I face as a performer is that you get these sort of fans that are, I like to call them ‘the Burning-man fans.’ They basically want to have a giant RoboCop on stage all the time. They want this big embellishment of something that entertains them while they’re on drugs or while they’re on their weekend warrior from working at Google — they want to just see the biggest dinosaur breathing fire.

I think as much as I’m not trying to be like over-intellectualizing things, I think going to art school was probably the best thing I could do, because before then I was all into making these sort of performances that would be bright and big. I think what you really want is what’s feasible and what’s a meaningful interaction. I always try to find these elements that are very simple motions like a rotation, a slide, maybe a throttle, something that has pushback and a tactile nature. You can really look towards early industrial machinery because they really found ways to be like “hey this is somebody that’s working, but we can’t overwork them, it can’t be too big, it can’t be too small.” I would say we’re really looking at early industrial America. Industrial tools are where we draw from.