Growing up, rituals were a big part of her “orthodox” family, says Bengali-American food historian and author Chitrita Banerji. “I instinctively incorporated them in my perceptions about food as I grew up.”

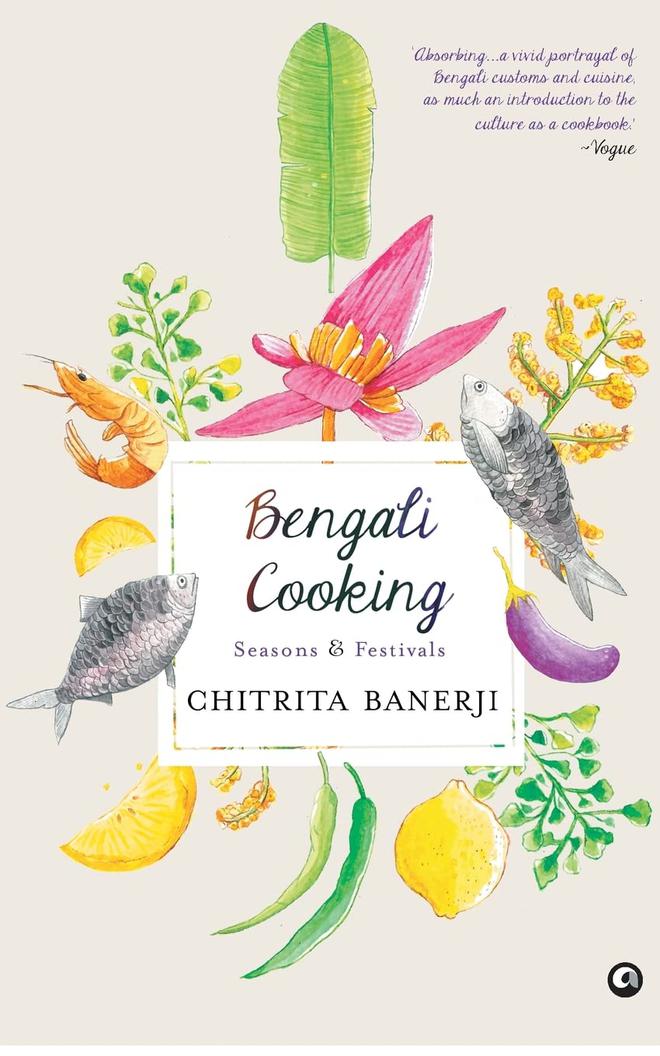

Banerji’s food journey has spanned decades and continents, ever since she started researching the history of Bengali food and culture for Life and Food in Bengal, published in 1991 (now available as Bengali Cooking: Seasons and Festivals). The book gives a heady whiff of every season, and the festivals and food it embraces.

“During that period [the making of the book], I was staying in Calcutta and I was fortunate enough to have access to many historical accounts that helped me see how food, society, religion, politics, and human behaviour were deeply enmeshed with each other,” says the Massachusetts-based writer.

The 76-year-old author, now working on a novel set in the 1930s, ably uses food as a medium of storytelling. Her 2021 book, A Taste of My Life, is one such collection that captures a vast spectrum of food memories — from the flavours of eastern India’s khejur gur to Bengal’s varied berries, and croissants and coffee that speak of grief. “I have never separated food from the other aspects of life. I find the term ‘food writer’ rather limiting.” Food, says Banerji, can be the trigger behind human responses, which, in turn, create “the stories of our lives”.

“Cook with focus and patience; if things don’t go as expected, don’t be afraid to improvise. Imagination is the key to good cooking.”Chitrita Banerji

Missed opportunity

Most of the Bengali recipes in her book are from the kitchens of family members and friends, says Banerji. But she deeply regrets not having learnt more from her mother — in particular, not having learnt to make the traditional sweets that are usually homemade. “They have been made for centuries using widely available indigenous ingredients such as wheat flour, rice flour, coconut, milk, rice, sugar and gur. Because of that, we sometimes take them for granted but I believe that in their execution they require as much finesse as the dishes made by professional chefs. I particularly miss my mother’s rice flour pithas as well as the crisp yet melt-in-the mouth sweet called jibey goja she used to make for me. Perhaps I didn’t try hard to learn because I was convinced I didn’t have the touch they required,” she says.

Banerji believes the Internet has helped spark a renewed interest in dying, traditional or elaborate Indian recipes. “The incredible accessibility provided by the Internet has not only aroused a great deal of interest in food and cooking, it has also created platforms where people can bring up many rare or forgotten ways of preparing food. Discussions around such topics stimulate the desire to revive techniques, methods and ingredients that had receded in our collective memory,” she says.

And, “the whole point of preserving traditions of any kind is to make it real and appealing for the younger generation who will be carrying the torch, as it were. So, some adaptation, experimentation, and innovation are essential to prevent traditions from becoming stagnant and lifeless,” she concludes.

Lamb with posto

Ingredients (for 4)

Method

The writer is a food columnist.