As predators at the top of the food chain, dolphins tend to accumulate and magnify high levels of toxins and other chemicals in their bodies. So health problems in dolphins can be a warning that all is not well in the system as a whole.

One group of persistent pollutants has been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they almost never break down in the environment. Commonly known by the acronym PFAS, these per- and polyfluorinated substances are globally recognised as an environmental hazard and a potential human health issue.

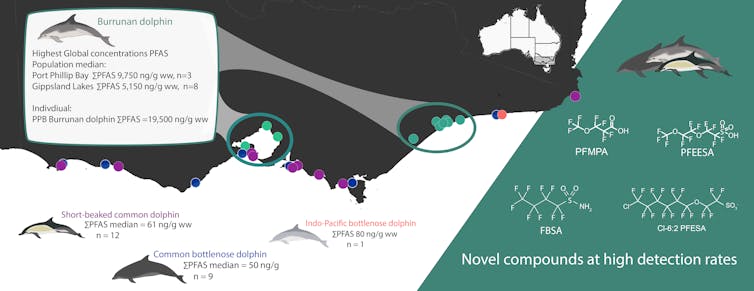

In our new research, we found dolphins with the highest concentration of PFAS in the world live in Australian waters. One young Burrunan dolphin had liver concentrations almost 30% higher than any other dolphin ever reported.

This is a critically endangered species endemic to southeast Australia. While the consequences for dolphin health and the implications for humans remain unknown, the record-breaking concentrations are cause for alarm.

The case of the Burrunan dolphin

The Burrunan dolphin was recognised as a separate species in 2011. Fewer than 200 individuals remain. Two small, isolated and genetically distinct populations reside in coastal Victoria, Australia.

In our research, we took liver samples from Burrunan dolphins and three other dolphin species found dead and washed up on beaches.

We found the critically endangered Burrunan dolphin had 50–100 times more PFAS than other dolphins in the same region. Their PFAS concentrations were the highest reported globally.

In 90% of these dolphins, the liver concentrations of these chemicals (1,020–19,500 nanograms per gram) were above those thought to cause liver toxicity and altered immune responses.

These record-breaking and potentially health-compromising PFAS concentrations are a major concern for the survival of the species.

Results from Australia and around the world

By far the highest PFAS concentrations in the dolphins we studied were of a particular compound called PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonate). PFOS is one of the most studied PFAS compounds. It is listed on the Stockholm Convention, a global treaty on environmental pollutants, with international restrictions on use.

While Australia does not manufacture PFOS, heavy use of PFOS-containing firefighting foams occurred until the early 2000s. The Australian government still allows PFOS import for permitted purposes, such as mist suppressants in manufacturing and metal plating.

In recent years, public concern has prompted ongoing investigations into areas of high firefighting foam use, such as Royal Australian Airforce training facilities and airports.

While firefighting foam is a probable source of PFAS in waterways, there are others. Recent research in Florida in the United States found leaking septic and wastewater systems in urban areas were sources of PFAS runoff into the aquatic environment.

The Burrunan dolphins are not alone. In 2017, the South Australian Environment Protection Authority investigated PFOS concentrations in dolphins from Western Australia, South Australia and New South Wales. Dolphins in the Swan-Canning River Estuary in Perth, and in Port River or Barker Inlet, SA, had high PFOS levels (2,800–14,000ng per gram and 510–5,000ng per gram, respectively). These PFOS levels are similar to those in the Burrunan dolphin (between 494ng and 18,700ng per gram).

The globally significant PFAS and PFOS concentrations in multiple Australian dolphin populations demonstrates potential widespread contamination. This highlights our limited understanding of the short- and long-term consequences in our oceans and estuaries.

It is crucial we understand where different PFAS compounds are coming from, particularly PFOS, and whether the contamination is from a time when we didn’t know better (known as legacy sources) or if we are still releasing them.

Isn’t PFOS getting banned anyway?

The Australian government has expressed an intention to further regulate PFOS and two other PFAS. This marks a significant step forward. However, the problem with forever chemicals is they will be around for a really long time.

Typically, these chemicals are substituted with alternatives believed to be less detrimental, but unfortunately that is not always the reality. For example, early replacements for PFOS were initially thought to be less readily absorbed by body tissues and pose lower health concerns. But studies have shown their high biomagnification potential (with levels increasing higher up the food chain) and accompanying health risks.

While PFOS levels were highest in the Burrunan dolphins we studied, emerging contaminants such as PFMPA, PFECHS, and 6:2 Cl-PFESA were also detected. The presence of these emerging and replacement compounds in dolphins shows they are accumulating within our waterways and suggests it is more than our historic usage that might be a problem.

It’s not too late

Dolphins are the “canary in the coal mine” for coastal ecosystems. They live their lives in these inshore waterways and they consume tonnes of fish within their lifetimes. Finding these alarming contaminant concentrations is an important first step to highlighting the problem.

So now we know there’s a problem, we need to ask why. Then we need to determine what can be done about it.

The next step is mapping sources of PFAS so we can more effectively manage this threat to our wildlife and ecosystems.

Read more: We found long-banned pollutants in the very deepest part of the ocean

Chantel Foord receives funding from a Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment Grant. She is affiliated with the Marine Mammal Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.