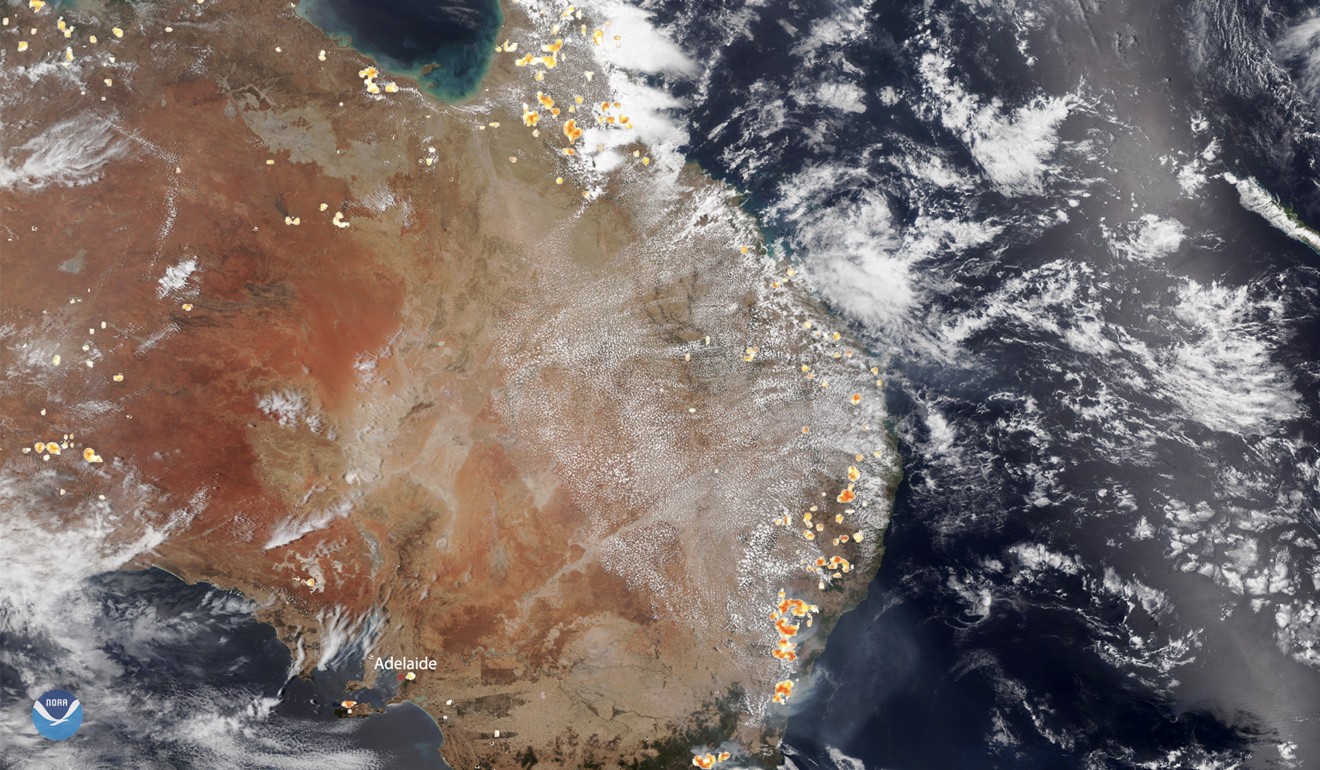

Australia is under the international spotlight as massive bush fires rage across vast swathes of the country, leaving death and destruction in their wake. Shocking images of devastation in a country known for its natural environment and laid-back lifestyle have reverberated around the world.

HOW BAD ARE THE FIRES?

The wildfires have killed at least 18 people and destroyed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of homes in regional areas of New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia since October. Some of the greatest devastation has occurred in the last fortnight, with 10 people killed and hundreds of properties lost since Christmas Day alone. Dozens more are injured or missing. More than 5 million hectares, an area greater than the size of Wales, have been burned.

On Thursday, the Premier of New South Wales, the country’s most populous state, declared a state of emergency, allowing for the forcible evacuation of residents, as authorities predicted even more intense fires due to a forecast spike in temperatures during the weekend.

BUSH FIRES ARE COMMON IN AUSTRALIA – WHAT’S DIFFERENT THIS TIME?

Bush fires are frequent during the Australian summer, which runs from December to February, and have posed a threat to lives and property on a large scale before. In 2009, the Black Saturday bush fires in the southern state of Victoria claimed 173 lives, the single largest loss of life from wildfires in Australian history.

But this season’s fires are widely seen as unprecedented for their intensity, scale and timing.

“Despite the availability of modern firefighting and hazard reduction methods, the burnt area is estimated to be already close to 6 million hectares, more than anything recorded ever before,” said Petr Matous, a senior lecturer at the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Sydney.

Mark Howden, director of the Climate Change Institute at the Australian National University, said the bush fires appeared to be “a less than a one-in-a-hundred year event.”

“The fire service chiefs are unequivocal in their assessment that this is an unprecedentedly severe fire season,” Howden said. “What appears to be different in this fire season is the sheer spatial extent of the fires – a combination of ferocious and very extensive. This combination has stretched firefighting capabilities.”

David Karoly, leader of the Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub at national science agency CSIRO, said the fires had arrived much earlier in the year than usual.

“The duration of these extreme fires is also unprecedented, starting early in spring and continuing through summer, affecting Queensland and New South Wales first in September and October, with continuous fires burning in a number of places from November through to January,” he said.

WHAT’S THIS TO DO WITH CLIMATE CHANGE?

Experts widely agree that a changing climate is increasing the likelihood of bush fires and that more extreme fires are likely to become more common as temperatures continue to rise in the future. Australia experienced its hottest and driest year on record in 2019, according to the country’s Bureau of Meteorology, with the national average daily temperature record broken twice in December.

“We know that fire risk is driven by four main factors: drought conditions which result in very dry fuel – leaves, grass, branches etc – high temperatures, high winds and dry air,” Howden said. “There is increasing evidence that climate change is driving more drought conditions, particularly in the mid-latitudes where Australia sits. There is extremely strong evidence that temperature increases are being driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases.”

Tina Bell, a senior lecturer in fire ecology at the University of Sydney, said that changing vegetation as a result of hotter weather was increasing the risk of bush fires.

“Vegetation is of course the fuel for fires and changing weather affects how fuels accumulate and dry – how flammable it becomes throughout the year, particularly if it is a drought year with lower than normal rainfall,” Bell said.

WHAT IS THE GOVERNMENT SAYING ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE?

While acknowledging a link between reducing emissions and the risk of bush fires, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has dismissed calls to take stronger action to combat climate change, insisting that current policy takes a balanced approach.

“Let me be clear to the Australian people, our emissions reductions policies will both protect our environment and seek to reduce the risk and hazard we are seeing today,” Morrison said on Thursday. “At the same time, it will seek to make sure the viability of people’s jobs and livelihoods, all around the country.”

Morrison has insisted the country remains on target to meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement to cut 2005-level emissions by 26 per cent by 2030, partly by using credits saved up under the earlier Kyoto Protocol.

Critics accuse the government of using accounting tricks to avoid making reductions in emissions that are large enough to stave off the worst effects of climate change.

In the 2020 Climate Change Performance Index, released last month by a group of think tanks focused on climate change, Australia was rated as having the worst climate change policies among 57 countries assessed.

IS THERE AN END IN SIGHT?

With the Australian summer continuing until March, authorities have warned that the crisis could drag on for months and is likely to worsen before it gets better.

The Bureau of Meteorology has forecast hotter and drier weather than average for January-March, while Shane Fitzsimmons, the commissioner for rural fire services in New South Wales, last month warned it could be February before there was rainfall heavy enough to make any impact on the fires.

Looking long-term, climate experts say that extreme bush fires are likely to become a more regular occurrence as the climate continues to get hotter.

“We will see even more severe fire weather conditions in the future, not every year, but every time that Australia has a drought,” said Karoly at CSIRO. “We expect even worse heatwaves, more frequent droughts in some parts of the country and more extreme fire danger conditions due to climate change.”